Illuminating Colonization Through Augmented Reality

Seema Rao, Brilliant Idea Studio, USA, Margaret Middleton, Margaret Middleton Exhibit Design and Museum Consulting, USA

Abstract

In 2018, French President Emmanuel Macron asserted French museums and private collections needed to reconsider their ownership of African objects. Macron’s comments come as museums are increasingly being questioned about issues of colonialism and their collections. Colonialism underscores many aspects of museums, from the very foundations of these institutions. Decolonization is an exceptionally challenging problem facing museums today; many of the diversity and access problems stem from the field’s colonialist past. In this paper, we posit methods that technology can help decolonize museums and collections. Museum technologists can become active agents of decolonization in collections and transforming the future of the field.Keywords: Decolonization, Augmented Reality

Introduction: The State of Colonialism in Museums And AR

In 2018, French President Emmanuel Macron asserted “African heritage cannot just be in European private collections and museums.” His comment refers to the scores of objects now residing in French museums, thanks to generations of the French occupation of African lands. France is not alone in its consideration of the ethical implications of colonially produced collections. Germany has allocated 3.5 million dollars for 2019 to consider the legality of objects in national collections (Macauley and Noack, 2018). This high-level acknowledgment of potential illegitimacy of Western collections comes after years of academic research and political advocacy from post-colonial nations and peoples. Millions of objects left colonial nations to be housed in European and North American museums for more than one hundred years—spoils of war to be enjoyed in the display cases of the victors.

The concomitant movement of colonial subjects to imperial nations further complicates the ideas of ownership. The majority of the galleries of the British museum house collections from nations outside the British Isles, for example. However, the ethnic makeup of the United Kingdom, and particularly London, includes many British nationals who themselves hail from those nations. Collections are, therefore, like post-colonial peoples, positioned in existential in-betweenness, at once from somewhere else and at home. Louis-Georges Tin, a representative of black associations in France who has influenced Macron’s position on lost art, characterizes the possible futures of collections, with these complications in mind, well: “To restitute is difficult. But not to restitute is even more difficult.” (Macauley and Noack, 2018). In other words, there is no one single solution to the problems colonialism have wrought on the museum field.

With such complexity, how can technology help museums in their decolonization efforts? This paper considers how augmented reality can be used as a collaborative tool to help museums decolonize their processes and produce interactives to help visitors engage with decolonization. The paper begins by unpacking colonialism in museums, touches on steps to decolonize museums, shares justifications for the use of AR as an activist engagement in museums, and then offers a framework for museums to employ AR in decolonization efforts.

Colonialism as the Mother of Museums

Museums are often cited as the most trusted force in society (Lemle, 2018). This trustworthiness highlights a fundamental flaw of the field. Museums have not existed, time immemorial. Instead, museums were born of a specific historical moment, the period of colonialism. Museums, however, give an air of immovable, neutral solidity, which makes changing the field ever-more challenging. But the foundations of museums bear the deep cracks from their origins in the colonial enterprise.

Colonialism is the practice of one group of people taking authority over another, often through conquest. European colonialism transformed the globe. By the 1400s, Europeans, in possession of fast ships and a quickening desire for profits, subjugated nations and peoples the world over. While Europe, Asia, and Africa had likely seen intercultural exchange for millennia, the pace of cultural diffusion increased exponentially in the period of colonialism (Chwatal, 2018). Full of the earnest intellectual fervor of the Enlightenment, European colonialists endeavored to catalog these new-to-them cultures. As with all forms of meaning-making, Europeans worked within their constructs and scaffolding tools. Europeans understood the rest of the world in relation to theirs. This flawed, Eurocentric reasoning was ontologically infused into the foundations of the very concept of museums. It is important to note the very concept of museums cannot be disentangled from this colonial root.

Early museums set up an evolutionary structure with European systems of knowing as the apex. Civilized humanity in Europe could go to any major museum to explore how the lesser orders existed (Zhang, 2017). A museum, as described in the Ephraim Chambers Cyclopædia of 1750, was “any place set apart as a repository for things that have some immediate relation to the arts, or to the muses,” while a repository was “a store-house or place where things are laid-up, and kept.” (Duthie, 2011). Early museums were set apart from warehouses by the act of curating meaningful arrangements. Museums were a place “to instruct the mind and sow the seeds of Virtue” as noted by Charles Willson Peale, founder of the Philadelphia Museum in 1784. These spaces were meant to be visited by the well-heeled, who had the proper disposition and pre-knowledge to appreciate the nuance of museum installations (Diethorn, n.d.). Museums were in keeping with a host of amateur activities pursued by gentlemen during their leisure. Contemplation and conversation over objects were leisure pursuits for a certain class of men.

The idea of museums spread quickly along the same networks that supported the colonialism of the age. By the early 19th century, museums were found on all inhabited continents. But, by this time, museums had already changed substantively. Rather than being for a select group of educated men, museums were now seen as a place for the general public. Additionally, visitors were allowed to self-guide through museums rather than taking a prescribed tour of the galleries. With the inclusion of all types of people, museums began to foreground their educational nature. In their first century, they could be assured an audience with the necessary foundations to understand the collection. But, in the 19th century, James Smithson, founder of the Smithsonian, said museums are “for the increase and diffusion of knowledge.” (History, n.d.). Museums were a method of sharing an ideological framework of society, if a flawed one.

Colonialism infuses every aspect of museum practice starting with the very existence of collection, spreading through the field like tendrils, entwining within every aspect of museum work, and becoming manifest in every practice from installation to interpretation. The fundamental aspect of colonialism in museum work makes decolonizing museums challenging, even revolutionary (Small, 2011). It requires museums to cede their authority and power of nominating a particular form of history (Procter, 2018). Decolonization requires the reconsideration of every aspect of work, down to the collections themselves and the concept of ownership (Edwards, 2018).

Decolonizing Museums

As Waziyatawin and Michael Yellow Bird state in their Introduction to For Indigenous Minds Only: A Decolonization Handbook, “Decolonization is the meaningful and active resistance to the forces of colonialism that perpetuate the subjugation and/or exploitation of our minds, bodies, and lands.” (2012). While the first colonial nations were ceded back to their indigenous inhabitants in the middle of the 20th century, museums remained solidly colonial for decades (Bonilla, n.d.).

Artist Fred Wilson’s groundbreaking work is cited as a seminal moment in decolonizing museums. Wilson’s art process often combines production with incursions into the practice of museology. His 1992 rehanging of the Maryland Historical Society for his artwork Mining the Museum, reframed the existing collection by creating different narratives through purposeful, and often satirical, juxtapositions. Of the installation, Wilson said, “What they put on view says a lot about a museum, but what they don’t put on view says even more.” (Fusco, 1994). Wilson’s work brought into focus the subjectivity of museum narratives and the lack of neutrality inherent in curatorial practice. Wilson also noted that his work seeks to remind viewers that the aesthetic practices of the museum, with their analytical installations, imply a false ahistoricism predicated on imperialist power. By dislocating objects from the complexity of their history, museums are denuding collections of elements of their history (Wilson, 2001). In essence, colonial practices place museums in the position of turning their backs on their very missions: to thoroughly understand and preserve collections and their history.

Nearly three decades after Wilson’s installation, museums use similar methods to attempt to decolonize collections. In Vienna, in 2018, the Weltmuseum installed an exhibition, Staying with Trouble, where artist Rajkamal Kahlon reinstalled their ethnographic collections. Other artist incursions have been employed similarly across Europe and North America. Scholar Chwatal rightly points to the inadequacies of such efforts (2018). While Wilson’s work served as a signal and call to action for transformation, subsequent reinstallations are stop-gap measures. Decolonization cannot simply be the temporary reinstallation of a single gallery. Museums need to see decolonization as a systematic and ongoing activity. As activists from “Decolonize This Place” note, museums maintain the colonial order from their leadership and funding to their staffing structures. Every aspect of museums is complicit, and as such, systemic change is required for change (Schwartz, 2018). Power, for example, is generally maintained by the largely white leadership, whereas the large minority guards and front-of-house staff have little power (Rao, 2017).

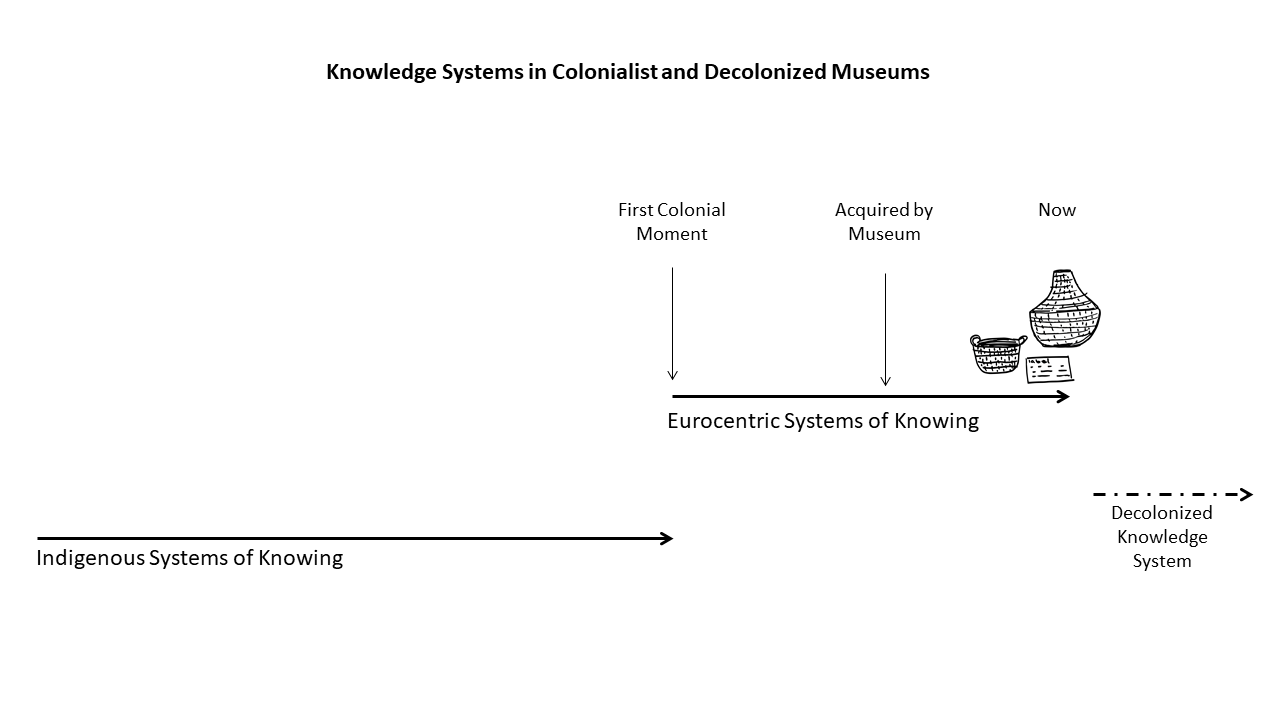

Colonialism fundamentally changed society. Thought and peoples were transformed. Collections cannot be shared as part of a distant past without acknowledgment of the present. History might be perceived as being fractured through colonialism. Decolonizing will not take collection narratives to the pre-colonial past, but to a new position, one that is a neither the old one or the Eurocentric one.

With the high level of inculcation in the field, the practice of decolonizing museums can seem overwhelming. Yet without undergoing systemic change, museums are liable to remain unresponsive to the changes in society, where cultural narratives and ownership are changing at the speed of social media. Many scholars have discussed the practice of decolonizing museums. Rather than rehashing those tools, this paper will summarize the key steps in decolonizing museum practice.

Decolonization requires purposeful, systematic, and systemic action, all of which should be undertaken with strategic fortitude and holistic fervor. As colonialism is congenitally fused to the foundations of museums, decolonization requires facing the fundamental transformation of the underpinnings of our discipline. The following decolonization steps are neither easy nor simple. Decolonization is like coming to terms with the uncomfortable circumstances of one’s birth in order to charter a new, better future. Without decolonizing, however, the future of our field will be mired in falsehood and inaccuracy.

Decolonization should also be seen as a shift in power from the Eurocentric forces of museums towards indigenous people. Including indigenous voices is not easy. Museums need to face their own innate power structures, and make space for different voices. Additionally, museums have often included diverse, indigenous voices in erratic ways, often capitalizing on free equity. Museums need to be thoughtful about compensating indigenous voices. Their input and impact on the museum’s future might be incalculable, but the importance of their work must be honored with remuneration. Along with a financial commitment, museums have to understand that decolonization requires a commitment of time. The whole history of Western organizations is imbued with colonialism, which will not be undone quickly.

In the globalized world, finding the correct indigenous peoples related to collections can be challenging. Scientific specimens for early humanoids, for example, might arguably have no extant indigenous descendants. Due diligence must be made to find groups who have a valid historical claim to a shared history with collections to serve as the voice for the originating culture. The task of finding indigenous voices should be undertaken with care. An approximation is not adequate. Time spent early in the project to find the appropriate indigenous voices, not just peoples who were from the same continent, for example, will save valuable time when any changes are rolled out. Visitors will notice mistakes made if the decolonization project didn’t engage the correct indigenous voices.

The decolonization efforts must begin with acknowledging and comprehending the effects of colonialism on our work. These pernicious effects of colonialism are so total as to make its effects invisible. Museums should assume every practice will come under consideration, and every museum functional area will be affected. The overall process requires intellectual and procedural changes that touch ways of thinking, systems of action, internal practices, and sources of authority. Steps include:

Break the Foundations

- Thinking: Understand that the organization will require the transformation of intellectual practices as well as underlying assumptions. Also, accept that the process of decolonization is ongoing and iterative. (Antoine et al., n.d. & Legutko, 2015)

- Thinking: Begin by accepting the colonial underpinnings of museums, including understanding these systems are not inherently “right” or “neutral” but instead socially constructed. (Rao, 2017)

- Thinking: Understand that decolonization is challenging and emotional but also a reflective and healing tool. (Moeke-Pickering, 2010)

Investigate the Cracks Colonialism Created

- Systems: Acknowledge the ways that museums have used power to support colonial practices. (Rhodes, Sims, & Potter-Ndiaye, 2018)

- Systems: Find new working processes that redistribute power. (Rhodes, Sims, & Potter-Ndiaye, 2018)

- Authority: Recognition of the authority of indigenous ways of knowing and ceding authority to those methods. (Ritske, 2014)

- Thinking: Accept ambivalence and contradictions between ways of knowing in European practice and indigenous practice. (Whitle, 2013)

- Authority: Center authority to indigenous ways of knowing. (Ng & AyAyQwaYakSheelth, 2018)

Form New Foundations

- Thinking: Understand that racism and colonialism are connected and contingent elements in our society, requiring mutual counteraction in order to eradicate either. (Moeke-Pickering, 2010)

- Practices: Develop feedback loops to remain accountable to indigenous contributors.

- Practices: Develop training with indigenous people, and then train everyone so that decolonization becomes inherent to the institutions.

- Practices: Transform the forms of communication, such as ensuring the language that asserts the personhood of all humans, like employing enslaved people rather than slaves. (Moeke-Pickering, 2010)

Decolonizing Technology in Museums

Technology is inherent to every museum practice. As such, technology, and the technological systems behind museum work must be scrutinized for their inherent colonialist elements. Ideally, technologists are actively engaging with the decolonization steps above alongside all the staff. The position of technology as support services to other museum practices, however, can create a blind-spot. Organizations might forget to investigate the ways colonialism effects digital practices. This oversight would be a huge mistake if an organization is serious about decolonizing.

Cataloging systems, for example, have inherent biases often born of the scholarly assumptions from which they sprung (Laroque, 2018). Authorship, for example, is a Eurocentric concept. In the West, the use of named artists is often seen in opposition to the term “anonymous,” often being used when an author or artist chooses to be unknown. In non-Western collections, anonymous is often left off labels and out of catalogs, employing the cultural area or historical period as the main identifier after the title instead. This practice is so common as to be unremarkable. However, the system effectively erases the humanity of non-Western artists. Think of the thousands of artists and creators missing from collection databases for non-Western objects. This serves as a massive erasure of humanity within museum systems. Why is anonymous often not used in non-Western collections? Non-Western creators are often classified as craftsmen, not artists worthy of naming their works. Therefore, the lack of a name is actually a double erasure, first of the indigenous person, and second of the validity of their labor.

Digital photography is another useful example of colonialism in museum technology. Organizations need to be careful to ensure all collections are photographed employing similar framing methods. For example, are ethnographic collections shot with different lighting effects than other collection objects? Or are non-Western sculptures shown with the main image, showing the object in profile as compared to other sculptures? These choices may seem inconsequential, but they are often imbued with Eurocentric assumptions.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is another element of museum technology worthy of vigilant consideration (Rao, 2019). As AI aggregates and analyzes human knowledge, the results are often a distillation of the biases, prejudices, and colonial attitudes within society. For example, when AI is used to analyze faces and emotions, they have greater problems with non-white faces. Emotions are culturally specific, and people have challenges understanding the emotions of people outside their culture (Cooley, et al., 2018; Conley et al., 2018; Thornton et al., 2018). Machines, therefore, gain similar biases, if not carefully scrutinized (Kaplan, 2018). For museum professionals, this element of decolonization is particularly essential when AI is used to power interactives. Without care, incorrect meaning can be placed on non-Western collections.

Technology can create digital simulacra of objects, effectively developing clones to serve as emissaries or stand-ins to be employed in other locations, like in their original homes. But it is imperative to note that technology cannot serve as a stand-in for repatriation efforts. The issue of repatriation is independent of the decolonization of museum technology.

AR, Museums, and Decolonization

Augmented reality (AR) is a projection of digital assets over real-world images in real time. Unlike virtual reality, in which users inhabit completely new worlds, AR juxtaposed the user’s real world with digitally generated worlds. In practice, AR is an umbrella term for a number of technology solutions. Consumers might be most familiar with mobile AR applications, like Pokemon Go, where the screen shows the imaginary creatures popping up in the user’s real world. Pokemon Go is the most commonly known form of AR, but there are numerous incarnations of this technology. For example, mobile can have broad diffusion, but AR can also be used through purpose-built headsets, which offers designers more control. AR is very often visual media overlays, as images offer immediacy. Text and sound can also be employed to great effect in mixed reality applications. The U.S. Army, for example, employs AR, with sound, text, and images, in simulations (INAP, 2018). AR can also verge on developing a completely different reality. For example, Patron Tequila produced an AR app to allow users to explore their liquor factory at home. The app allows users to move through space and manipulate elements (Paine, 2018). Overall, AR offers organizations myriad opportunities to reconsider real space through digital overlays that engage multiple senses, allow for kinesthetic engagement, foster deeper interpretation, and encourage play.

AR offers museums a particularly fruitful option to put decolonizing efforts into action. Decolonization requires the affordance for the complexity of interpretation, for example. This complexity, while often hard to communicate textually, can be demonstrated experientially. Objects are separated from their original context in museums. AR can return these settings, if virtually. This overlay feature of AR has been shown to have a significant impact on learners (Chang et al., 2015).

Scholars have also noted the way that contextual overlays have helped learners not only “see” the past for historical items but also engaged users on an emotional level. AR has been shown to help subvert biases (Franks, 2017). Olesky and Wnek’s (2017) work highlights the positive possibilities of AR for decreasing prejudice. Their study used AR to add context and meaning to places. They found participants were more emotionally engaged with the content and as such, they reduced bias toward the content with participants gaining an enhanced multicultural understanding of the content.

This emotional engagement is particularly important in helping users engage in decolonization on a fundamental level. Difficult topics are often about more than knowledge transmission. Emotional engagement is required to connect with the underlying prejudice and bias suffusing preconceived notions and uncalculated ideas. Studies have shown that students are better able to understand the importance of environmental education by using AR. Technology helps learners feel emotionally engaged in the subject (Huang, et al., 2016).

The high level of emotional engagement is likely due to the experiential, immersive nature of AR (Huang, et al., 2016). By drawing on the user’s innate sense of exploration, the use of attractive technologies increases users’ willingness not only to learn more about the environment but also to develop a more positive emotional attachment to it (Huang, et al., 2016). AR affords learners kinesthetic and visual reinforcements while concretizing intellectual concepts (Chen, Liu, Cheng, Huang, 2017).

Museum technology blends learning and experience. Therefore, the field should take note of the use of such tools in school settings. AR tools have been already shown to improves learning achievement (Akcayir & Akcayir, 2017). School studies indicate that AR is particularly beneficial to low-achieving students (Malmi, 2016). This success in the school setting is important for museum technologists. These lessons indicate that the tool can have great efficacy even for the recalcitrant. Decolonizing collections requires engaging all learners in ideas that feel fundamentally different than their accepted frames of references.

Finally, decolonizing requires increased empathy for indigenous people in order to understand their ways of knowing. AR has been shown to increase empathy. While the relationship between empathy and AR is complicated, the exploration aspect of AR offers users a high level of agency which has been demonstrated to have a positive correlation to increased empathy (Bertrand et al., 2018 & Fuentes, 2017).

The power of AR has already been employed by activists in artist-led projects (Skwarek, 2018). The ubiquity of cell phones and AR toolkits makes the technology an ideal platform for social action. The tool can easily add, as well as subtract from the world, without making any actual physical changes (Harding). Such digital incursions offer users intellectual surprises without placing artists in political uncertainty. Overall, AR offers agency and power, removing power from the curator in nominating the narrative and short-circuits narratives of victimhood.

Museums and AR

Museums have been exploring AR. The technology lends itself to playful implementations. The National Museum of Singapore’s Story of the Forest is a playful immersion into artworks made manifest through technology. The Art Gallery of Ontario’s ReBlink app blended engagement and fun to help visitors engage with collections differently. The Perez Museum of Art in Miami worked with artist Felice Grodin to create an AR app that is, for all intents and purposes, a virtual exhibition. In each those examples, visual overlays are preferenced over text (Coates, 2018).

Interpretation is a common use of AR in museums. The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s Skin & Bones app virtually adds physicality to the bones in their gallery displays. The app brings to life, if only virtually, bones that might otherwise feel clinical. (Billock, 2017). The Detroit Institute of Art’s Lumin uses a number of different interpretive approaches to AR (including overlaying visuals and employing text), to deepen visitor’s engagement with collections. Museum of London uses AR to take their interpretation outside the galleries, overlaying their collection photographs with users’ contemporary London (Zhang, 2010). The National Museum Cardiff created a virtual impressionism app to explore Monet’s world. Museums are employing AR to give interpretation that can’t be experienced in labels (Murphy, 2018).

The impetus to preference visuals and employ AR for interpretation are promising. However, museums have not adequately employed AR to help visitors engage with difficult topics. Some of the most surprising AR museum apps came from outside the museum. In the MOMAR app, for example, artists subverted the position of Jackson Pollock by overlaying images of underrepresented artists. Cuseum gained wide publicity for their app that brought artworks long-ago stolen back to the Isabella Stewart Gardner (Katz, 2018). Technologists, therefore, have a wide-open field to impact the ways that museums help visitors and community members engage with hard issues.

An Intellectual Framework to Employ AR as a Decolonization Tool

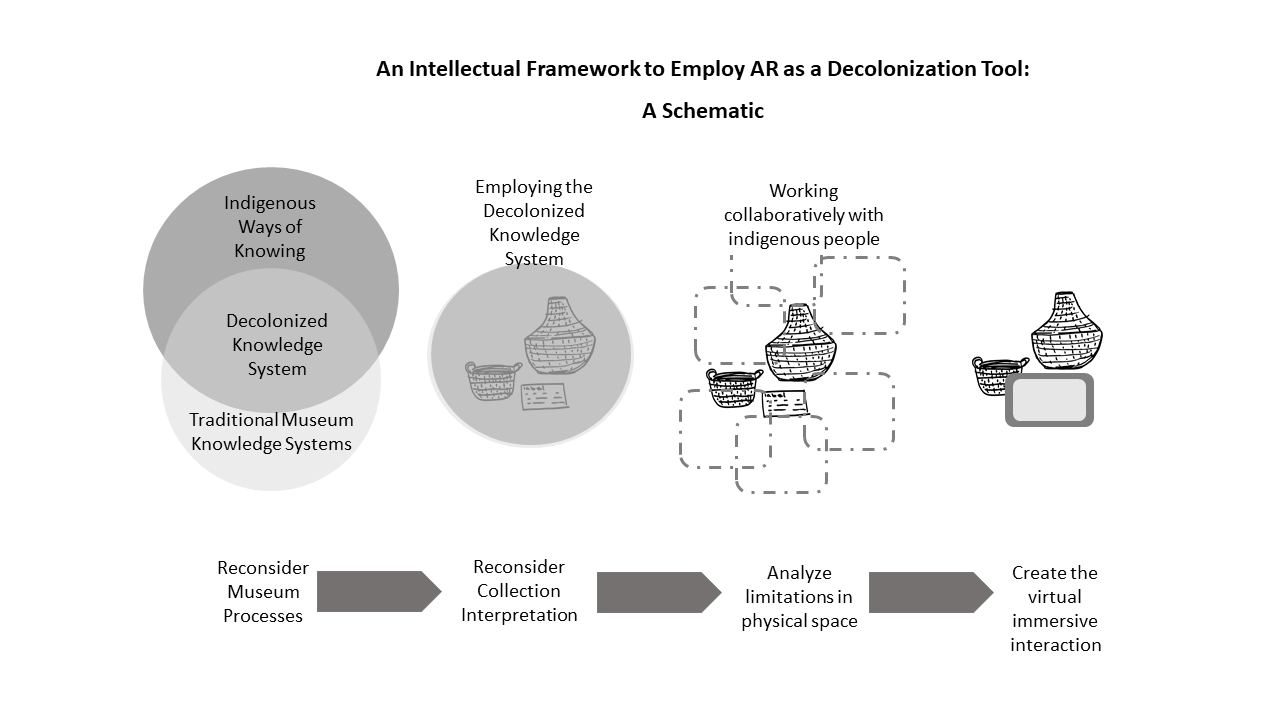

AR is a tool for experiential learning, but the production of AR interactives immerses content producers in a similarly experiential environment. As decolonization requires active engagement, AR is an ideal way for museums to put their decolonization efforts to use. The majority of the time and effort occurs long before an actual interactive is produced, as decolonization is largely intellectual labor.

This framework is essentially a work plan to make an AR interactive that is truly decolonized. This framework dovetails with the decolonization steps delineated above. Once an organization has engaged in those steps, they can employ these steps:

- Reconsider Museum Processes:

- Summarize the efforts of decolonization to date.

- Create a panel of indigenous people to serve as the AR co-planning team.

- Convene a conversation about the interpretation of collections where indigenous people interface with museum people.

- With a neutral mediator, develop a Decolonized Knowledge System that includes linguistic norms, stereotypes to be avoided, and essential ideas to be addressed.

- Reconsider Collection Interpretation:

- Employ indigenous people to explore the current forms of interpretation for limitations.

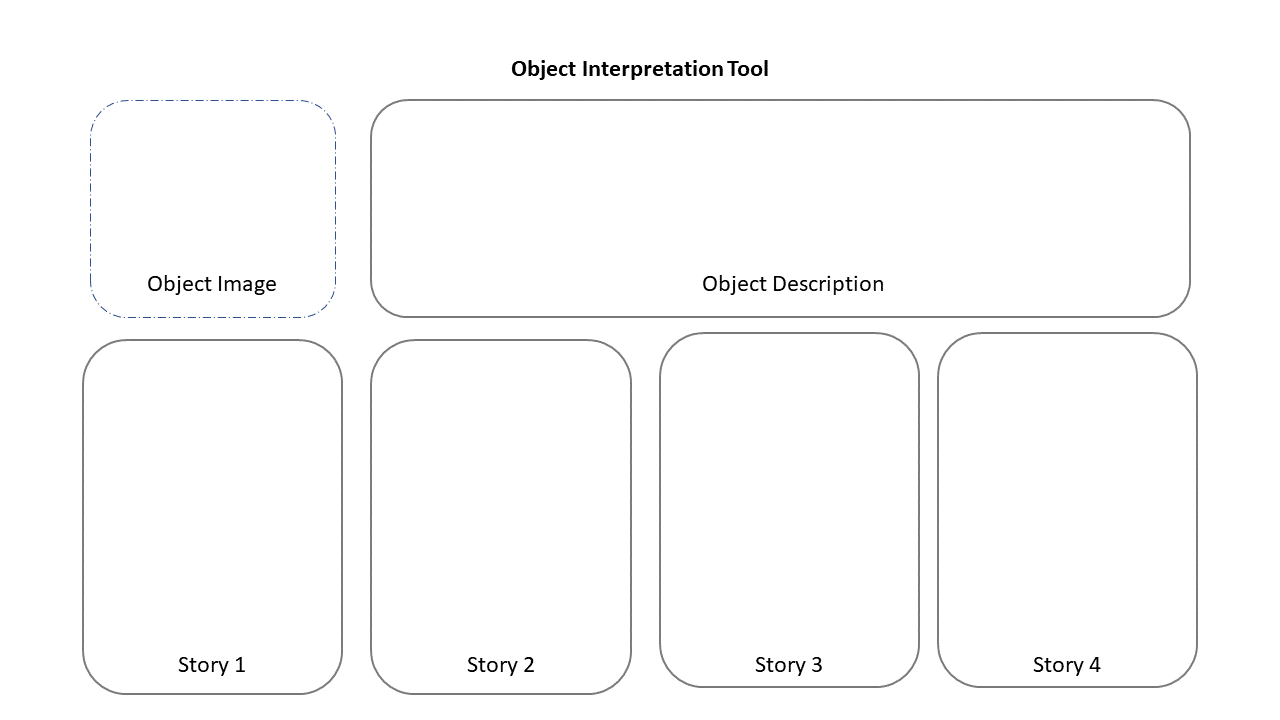

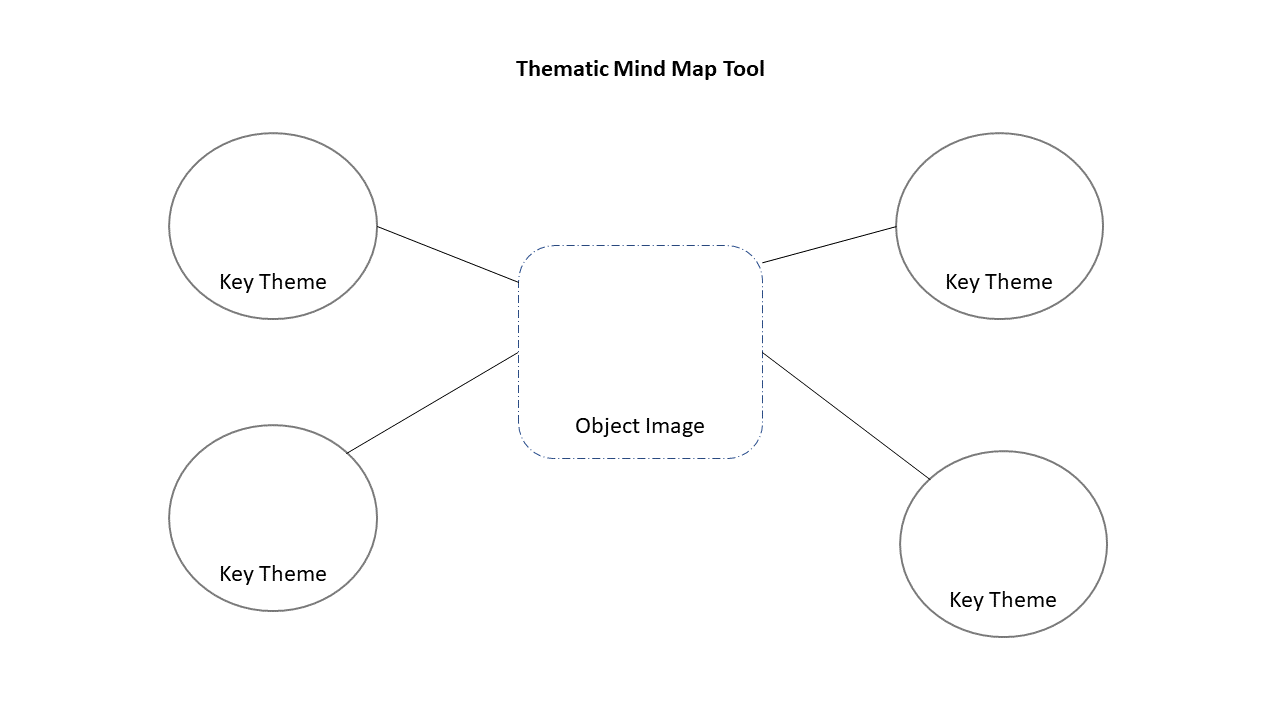

- Start by examining a set of collection objects to find trends in the limitations of interpretation between different collection objects. (Appendix 1: Object Interpretation Tool and Appendix 2: Thematic Mind Map Tool)

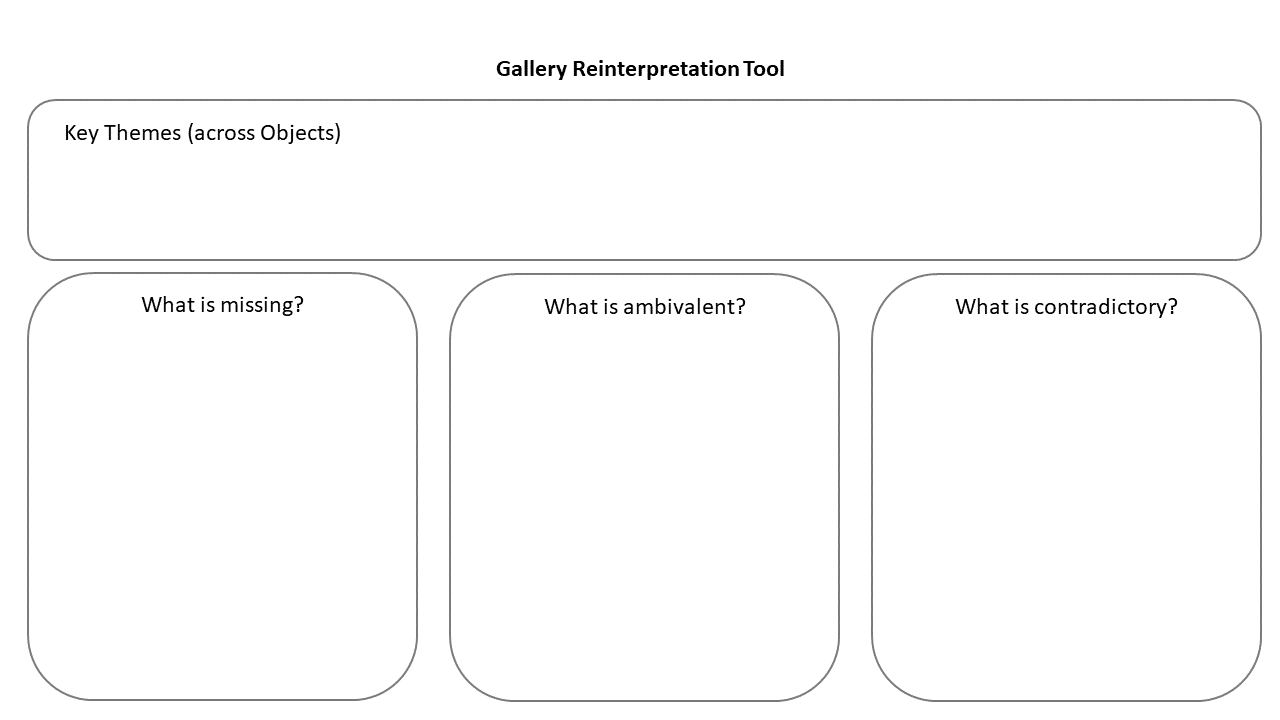

- Examine the galleries for limitations and problems. (Appendix 3: Gallery Reinterpretation Tool)

- Create guidelines to address limitations and develop benchmarks to ensure those limitations are not found in the AR product.

- Create goals for better interpretation.

- Analyze limitations in Physical Space:

- Work collectively to understand how the physical installation erases elements of the objects’ histories starting with the Gallery Reinterpretation Tool as a guideline for growth.

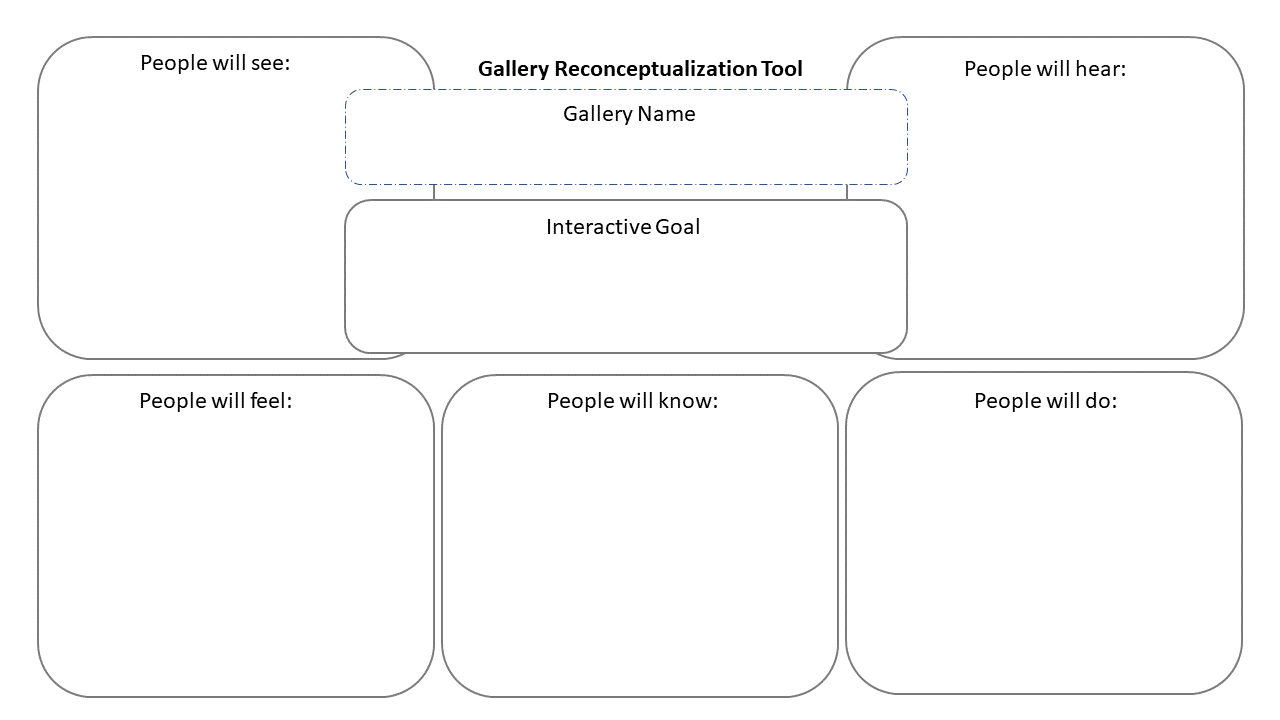

- Develop a large list of possible narratives by asking each participant to imagine an ideal interpretation of collections. Have them employ all their senses in their planning. (Appendix 4: Gallery Reconceptualization Tool)

- Allow indigenous voices to nominate the voices to be used in the interactive. Confirm the list of narratives to be used in the interactives.

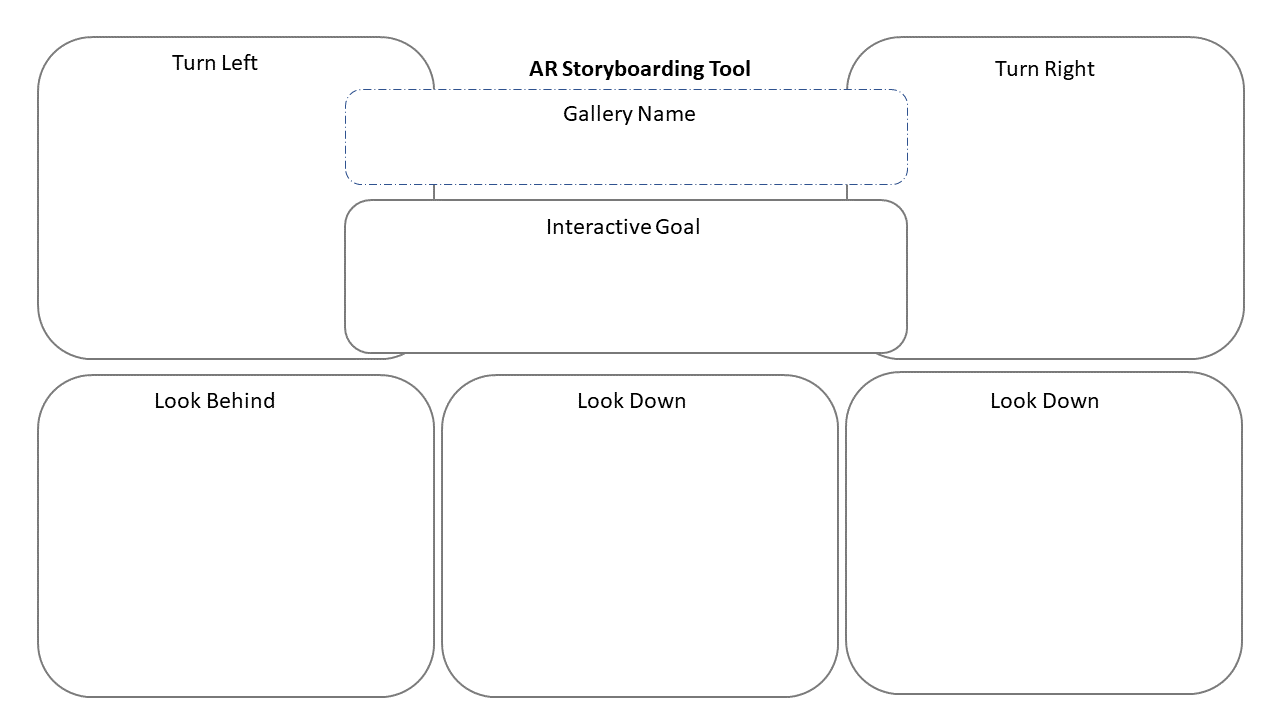

- Imagine the interactive collaboratively. (Appendix 5: AR Storyboarding Tool and Appendix 6: AR Sequencing Tool)

- Compare the storyboards and sequences across the team. Collaboratively choose a set to be in the interactive.

- Create proof of concept images/low-fidelity sketches for community discussion panels. Work through any possible limitations with the content. (Cerejo, 2010)

- Create the immersive virtual interaction

- Bring the designers (if out-of-house) into the collaborative decolonized space. (Ideally, they have been participating in the decolonization aspects in step 3 as silent observers).

- Create a list of elements that could be problematic if produced incorrectly, so that designers are not accidentally working against decolonization efforts.

- Develop a work plan to create the interactive.

- Ensure all the sensory materials (sounds, finishes, visuals) are vetted by the indigenous co-planners.

- Create a prototype to test.

- Train indigenous people to test the interactive.

- Employ test results to improve the interactive.

- Launch the interactive.

This framework draws on Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory, which suggests learners require active experimentation, observation, and reflection to transform abstract concepts into concrete meaning (MacLeod, 2017). This framework employs this experiential learning theory in both the creation of the content and in the ways that users would engage the content. The process of creating the interactive actively reinforces decolonizing the museum as they produce a product that supports visitors also engaging the same practice of decolonization.

At essence, the framework is a tool to help museum workers and indigenous people work together to collaborate over collections. This work must be engaged without preconceived notions. For example, one might assume that AR for decolonization would erase collection objects acquired during the colonial era. However, a post-colonial subject might instead see parallels between the object’s history, and their own. They might suggest a completely different form of digital interpretation. However, with due diligence, working carefully through the steps of the framework, these intellectual fallacies will not occur, as the team will come to the content of the AR interactive collectively.

Often teams want to jump into planning, sketching on template wireframes. In order to avoid colonialist traps, avoid this urge. The process requires collective thinking and content creation that takes time. Fixing upon concrete elements too early could mask mistakes. Once the team is able to focus on the interactive, the designers will be able to help them create an experience that is immersive rather than cinematic (Warner, 2017). For example, while AR sequences are useful to consider, these are often accessed by users in non-sequential ways. When the team conceptualizes the interactives, they should walk through physical spaces and discuss the content (Warner, 2017).

Finally, the AR app needs to be tested collaboratively with the indigenous planners, ideally having them trained as evaluators. This process might sound onerous. However, shared authorship results in shared ownership and shared success. Following this process, the final product will be a manifestation of decolonization efforts from onset to use.

Conclusion

AR as a storytelling tool is immersive and non-invasive. Given that objects can be seen with layers of narratives, histories unseen and oft unknown, AR can visually share hereto invisible narratives. Building on the activist culture of AR, the tool change can be used to subvert museums privileged position of nominating the “correct” or canonical narrative.

However, AR is not a panacea. The AR Decolonization Framework must be employed after a museum has engaged in decolonizing their practices. This system requires museums to already understand the ways colonialism are born in their culture and practices. However, once the museum has engaged with decolonization, AR affords them a useful tool to collaborate beyond the existing narratives of collections bringing in collective voices toward a better, deeper engagement with visitors.

Overall, AR could be an indispensable tool for museums to transform from a position of Enlightenment-derived intellectual authority to shared-authority spaces. The return on investment would be huge, increasing the validity of their interpretation considerably but also making collections more relevant to an ever-increasing global audience. Collaborative planning with indigenous peoples can surface uncomfortable truths and expose the lack of neutrality in museum spaces. However, shared authorship projects will offer enormous dividends for visitors using the content.

The opportunities for AR to transform museum practice toward a better, decolonized future are enormous. AR juxtaposes reality and computer-generated possibilities in a way that can surface the often invisible elements of colonialism in all museum spaces. The ephemerality of AR can make this tool ideal, as it can feel like a better space for collaboration with people outside the museum. AR is already a successful tool for museum interpretation and exploration. The possibilities are available. Now, museums technologists need to harness the technology to transform museums for the better.

Appendix 1: Object Interpretation Tool

Appendix 2: Thematic Mindmap Tool

Appendix 3: Gallery Reinterpretation Tool

Appendix 4: Gallery Reconceptualization Tool

Appendix 5: AR Storyboarding Tool

Appendix 5: AR Reality Sequencing Tool

References

“7 Incredible Examples of Augmented Reality Technology.” (2018, October 08). Retrieved February 11, 2019. Available at: https://www.inap.com/blog/7-incredible-examples-of-augmented-reality-technology/

Akçayır, M., & Akçayır, G. (2017). “Advantages and challenges associated with augmented reality for education: A systematic review of the literature.” Educational Research Review, 20, 1–11. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2016.11.002

Antoine, A., Mason, R., Mason, R., Palahicky, S., & De France, C. R. (n.d.). Pulling Together: A guide for Indigenization of post-secondary institutions. A professional learning series. Vancouver, BC: BCCampus. Available at: https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationcurriculumdevelopers/

Azuma, R. (2015). “Location-Based Mixed and Augmented Reality Storytelling.” 2nd Edition of Fundamentals of Wearable Computers and Augmented Reality, Woodrow Barfield, (ed.). CRC Press, 259-276.

Bertrand, P., Guegan, J., Robieux, L., McCall, C. A., & Zenasni, F. (2018). “Learning Empathy Through Virtual Reality: Multiple Strategies for Training Empathy-Related Abilities Using Body Ownership Illusions in Embodied Virtual Reality.” Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 5. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2018.00026

Billock, J. (2017). “Five Augmented Reality Experiences That Bring Museum Exhibits to Life.” Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved February 11, 2019. Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/expanding-exhibits-augmented-reality-180963810/

Bonilla, M. A. (n.d.). Some Theoretical and Empirical Aspects on the Decolonization of Western Collections. On Curating. Retrieved January 27, 2019. Available at: http://www.on-curating.org/issue-35-reader/some-theoretical-and-empirical-aspects-on-the-decolonization-of-western-collections.html#.XE25WlxKhEY

Cerejo, L. (2010). “Design Better And Faster With Rapid Prototyping.” Smashing Magazine. Retrieved January 28, 2019. Available at: https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2010/06/design-better-faster-with-rapid-prototyping/

Chang, Y., Hou, H. , Pan, C., Sung, Y. & Chang, K. (2015). “Apply an Augmented Reality in a Mobile Guidance to Increase Sense of Place for Heritage Places.” Journal of Educational Technology & Society, Vol. 18, No. 2., 166-178

Chen P., Liu X., Cheng W., Huang R. (2017). “A review of using Augmented Reality in Education from 2011 to 2016.” In: Popescu E. et al. (eds). Innovations in Smart Learning. Lecture Notes in Educational Technology. Springer, Singapore. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2419-1_2

Chwatal, C. (2018). “Decolonizing the Ethnographic Museum.” Art Papers. Retrieved January 27, 2019. Available at: https://www.artpapers.org/decolonizing-the-ethnographic-museum/

Coates, C. (2019). “How Museums are using Augmented Reality.” MuseumNext. Retrieved February 11, 2019. Available at: https://www.museumnext.com/2019/02/how-museums-are-using-augmented-reality/

Conley, M. I., Dellarco, D. V., Rubien-Thomas, E., Cohen, A. O., Cervera, A., Tottenham, N., & Casey, B. (2018). “The racially diverse affective expression (RADIATE) face stimulus set.” Psychiatry Research, 270, 1059–1067. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.04.066

Cooley, E., Winslow, H., Vojt, A., Shein, J., & Ho, J. (2018). “Bias at the intersection of identity: Conflicting social stereotypes of gender and race augment the perceived femininity and interpersonal warmth of smiling Black women.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 74, 43–49. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.08.007

Diethorn, K. (n.d.). “The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia.” Retrieved January 27, 2019. Available at: https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/peales-philadelphia-museum/

Duthie, E. (2011). “The British Museum: An Imperial Museum in a Post-Imperial World.” Public History Review, 18, 12–25. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5130/phrj.v18i0.1523

Edwards, E. (2018, April 19). “Addressing colonial narratives in museums.” Retrieved January 26, 2019. Available at: https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/blog/addressing-colonial-narratives-museums

Franks, Mary Anne (2017). “The Desert of the Unreal: Inequality in Virtual and Augmented Reality.” UC Davis Law Review, Vol. 51, 2017; University of Miami Legal Studies Research Paper No. 17-24. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3014529

Fuentes, J. L. (2017). “Augmented Reality and Pedagogical Anthropology: Reflections from the Philosophy of Education.” In J. M. Ariso (ed.), Augmented Reality. De Gruyter. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110497656-014

Fusco, C. (1994) “The Other History of Intercultural Performance,” TDR: Journal of Performance Studies 38, no. 1 (Spring), 148.

Hao, K. (2017, March 13). “The future of social-justice activism and mass-incarceration reform is in VR.” Quartz. Retrieved January 24, 2019. Available at: https://qz.com/930828/project-empathy-vr-backed-by-van-jones-is-a-virtual-reality-project-that-will-be-the-future-of-social-justice-activism-and-mass-incarceration-reform/

Harding, C. (2018, May 28). “Augmenting Art and Activism—Inborn Experience (UX in AR/VR).” Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/inborn-experience/augmenting-art-and-activism-6eadf14639cc

History. (n.d.). Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved January 27, 2019. Available at: https://www.si.edu/about/history

Huang, T.-C., Chen, C.-C., & Chou, Y.-W. (2016). “Animating eco-education: To see, feel, and discover in an augmented reality-based experiential learning environment.” Computers & Education, 96, 72–82. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.02.008

Kaplan, J. (2018). “Why your AI might be racist.” The Washington Post. Retrieved January 27, 2019. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2018/12/17/why-your-ai-might-be-racist/?utm_term=.dc76893e7e4a

Katz, M. (2018). “Augmented Reality Is Transforming Museums.” Wired Magazine. Retrieved February 11, 2019. Available at: https://www.wired.com/story/augmented-reality-art-museums/

Laroque, S. (2018). “Making Meaningful Connections and Relationships in Cataloguing Practices: The Decolonizing Description Project at University of Alberta Libraries.” Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 13(4). doi:10.18438/eblip29440

Legutko, C. (2015). “How Did We Come to Decolonization?” Available at: https://abbemuseum.wordpress.com/2015/11/11/how-did-we-come-to-decolonization/

Lemle, N. (2018). “Museums and Social Responsibility.” Culture Track. Retrieved January 27, 2019. Available at: https://culturetrack.com/ideas/museums-and-social-responsibility/

McAuley, J., & Noack, R. (2018). “European museums may loan back some works stolen from former colonies.” The Washington Post. Retrieved January 26, 2019. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/european-museums-may-loan-back-some-works-stolen-from-former-colonies/2018/08/08/ea0d8c16-95c2-11e8-818b-e9b7348cd87d_story.html?utm_term=.5447f649cd10

Mcleod, S. (2017). “Kolb’s Learning Styles and Experiential Learning Cycle.” Simply Psychology. Retrieved January 26, 2019. Available at: https://www.simplypsychology.org/learning-kolb.html

Moeke-Pickering, T. M. (2010). Decolonization as a social change framework and its impact on the development of indigenous-based curricula for helping professionals in mainstream tertiary education organizations (Master’s thesis, 2010). Hamilton: The University of Waikato.

Murphy, A. (2018). “Digital Museum Guides: Enhancing modern-day visits with audio guides, apps and AR.” Museums and Heritage. Retrieved February 11, 2019. Available at: https://advisor.museumsandheritage.com/features/digital-museum-guides-audio-apps-augmented-reality/

Myers, R. (2017). “Virtual Reality and Depth of Empathy.” In J. Dron & S. Mishra (eds.), Proceedings of E-Learn: World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE), 723-728. Retrieved January 24, 2019. Available at: https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/181251/.

Oleksy, T., & Wnuk, A. (2016). “Augmented places: An impact of embodied historical experience on attitudes towards places.” Computers in Human Behavior, 57, 11–16. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.014

Paine, J. (2018). “10 Brands Already Leveraging the Power of Augmented Reality.” Inc Magazine. Retrieved February 11, 2019. Available at: https://www.inc.com/james-paine/10-brands-already-leveraging-power-of-augmented-reality.html

Rao, S. (2017). “Trust the Revolution.” Brilliant Idea Studio. Retrieved January 27, 2019. Available at: https://brilliantideastudio.com/ideas/trust-the-revolution/

Rao, S. (2017). “Museums are not Neutral—Nothing is #MuseumsarenotNeutral.” Brilliant Idea Studio. Available at: https://brilliantideastudio.com/art-museums/museums-are-not-neutral/

Rao, S. (2019). “Museums and AI: Could Robots Be Your New Coworkers?” American Alliance of Museums. Retrieved January 27, 2019. Available at: https://www.aam-us.org/2018/12/26/museums-and-ai-could-robots-be-your-new-coworkers/

Rhodes, L. M., Sims, S., & Potter-Ndiaye, E. (2018). “Looking Inward: Addressing colonialism and racism in museum origin stories and collections (Part 1).” Retrieved January 27, 2019. Available at: http://www.museumedu.org/looking-inward-addressing-colonialism-racism-museum-origin-stories-collections-part-1/

Ritskes, E. (2014, June 18). “What is decolonization and why does it matter?” Retrieved January 27, 2019. Available at: https://intercontinentalcry.org/what-is-decolonization-and-why-does-it-matter/

Salmi, H., Thuneberg, H., & Vainikainen, M.P. (2016). “Making the invisible observable by Augmented Reality in informal science education context.” International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 7(3), 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/21548455.2016.1254358

Sauvage, & Alexandra. (2010). “To be or not to be colonial: Museums facing their exhibitions.” Retrieved January 26, 2019. Available at: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1870-11912010000200005

Schwartz, E. (2018). “How Do You Decolonize an Arts Institution?” Vice. Retrieved January 27, 2019. Available at: https://garage.vice.com/en_us/article/j5adn8/brooklyn-museum-decolonize-this-place-open-letter

Skwarek, M. (2018). “Augmented Reality Activism.” In Springer Series on Cultural Computing. Springer International Publishing, 3–40. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69932-5_1

Small, Stephen (2011) “Slavery, Colonialism and Museums Representations in Great Britain: Old and New Circuits of Migration,” Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge: Vol. 9 : Iss. 4 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarworks.umb.edu/humanarchitecture/vol9/iss4/10

Thornton, I. M., Srismith, D., Oxner, M., & Hayward, W. G. (2018). “Other-race faces are given more weight than own-race faces when assessing the composition of crowds.” Vision Research. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2018.02.008

Warner, L. (2017). “Mixed Reality User Flows: A New Kind of Template.” Prototypr. Retrieved January 28, 2019. Available at: https://blog.prototypr.io/mixed-reality-user-flows-a-new-kind-of-template-27d59991de4a

Waziyatawin, & Bird, M. Y. (2012). For indigenous minds only a decolonization handbook. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

Wilson, F. (2001). “Constructing the Spectacle of Culture in Museums.” Christian Kravagna (ed.). Artists on Institutional Critique, Cologne, 98.

Wintle, C. (2013). “Decolonising the Museum: The Case of the Imperial and Commonwealth Institutes. Museum & Society,11(2),” 185-201. Retrieved January 27, 2019. Available at: https://journals.le.ac.uk/ojs1/index.php/mas/article/viewFile/232/245

Zhang, M. (2010). “Museum of London Releases Augmented Reality App for Historical Photos.” PetaPixel. Retrieved February 11, 2019. Available at: https://petapixel.com/2010/05/24/museum-of-london-releases-augmented-reality-app-for-historical-photos/

Zhang, S. (2017). “The Museum of Colonialism.” The Atlantic. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/09/hans-sloane-british-museum/539763/

Cite as:

Rao, Seema and Middleton, Margaret. "Illuminating Colonization Through Augmented Reality." MW19: MW 2019. Published January 28, 2019. Consulted .

https://mw19.mwconf.org/paper/illuminating-colonization-through-augmented-reality/