Affect in Information Systems: A Knowledge Organization System Approach to Documenting Visitor-Artwork Experiences

Erin Canning, Aga Khan Museum, Canada

Abstract

Viewers of artworks exhibited in museums and galleries are known to experience felt reactions to art objects and exhibitions in a way that constitutes an important dimension of the public function of museums, complementary to their role as sites of learning and community. The ability of artworks to elicit such affective response is widely recognized, yet remains absent from museum documentation systems, standards, and methods. It is impossible to continue to ignore the gulf between the information that the museum wants to present to its publics, and the information that the museum collects and stores in its information systems. In this paper, based on my Master’s thesis (Canning, 2018), I discuss the development of a conceptual framework for the notion of affect in experiences of artworks within the art museum, and its manifestation in museum information systems and standards—namely, the inclusion of affective metadata, involving both a data model and corresponding taxonomy of affective terms. This system should be able to reliably represent the diversity and complexity of information related to the affective dimensions of the art-viewing experience. In addition to initial system development, I discuss the process and results of an empirical visitor-response study conducted to validate the proposed model, and the revisions and future work that came to light as a result of this study. In particular, I discuss the notion of empathy and connection-making that occurred between research participants and the artworks selected for the study. I conclude by examining how this process could be incorporated into the proposed model, and discuss the complexities in doing so.Keywords: affect, emotion, empathy, metadata, information systems, documentation

Introduction

Artworks and other museum objects are capable of eliciting a wide range of affective experiences for visitors, and the felt aspects of a museum visit are an important dimension of the museum experience. Visitors’ experiences in museums can only be explained if affective components are considered: affect and emotion are essential parts of the process of meaning—and identity-making in museums (Falk & Dierking, 2000; Smith & Campbell, 2016; Watson, 2015). The role that objects play in the felt experience of a museum visit is recognized in museum theory and practice, but remains absent from museum documentation systems, standards, and methods. Therefore, although ideas of affective experiences can be found in museological literature and practices in exhibition design, interpretation, and programming, they have not been considered in the design of the information systems used to document and manage museum collections. This has led to a critical gap in the capability of museum collections information systems to support information work in museums and to leverage this information to support visitor-centric missions. The disconnect between the visitor-facing goals of the museum, and the information systems designed to manage the museum’s collections, has therefore, become an increasingly apparent issue.

A data model and knowledge organization system for the inclusion of affective metadata is a necessary component of a strategy that addresses these issues at the level of the data structures on which collections information systems are developed. As such, affect needs to be considered within the scope of art museum object metadata, and existing museum metadata standards should be extended or revised to accommodate this knowledge. For the inclusion of affective metadata, both components are necessary: a data model to structure the insertion of affective metadata so that it they can be integrated into a data environment while maintaining the agency of the object, the exhibition context, and the viewer, and a knowledge organization system such as an affect thesaurus to enforce the vocabularies used to populate the metadata elements in order to ensure common understanding of the included terms. Such a system should be able to reliably represent the diversity and complexity of information related to the affective dimensions of the art-viewing experience.

Understanding Affect

Affect in the Art Museum

In the museum context, affect is attended to as a way for visitors to connect with objects and others (Smith & Campbell, 2016; Watson, 2015). Elements of the concept of affective experiences can be traced back to Dewey’s (1934) concept of the “aesthetic experience” and Iser (1978) and Jauss’ (1982) reception theory. These theories have been taken up by scholars such as Latham (2007, 2012) with her notion of the numinous experience, which challenges Dewey’s proviso that aesthetic experience can only come from an encounter with art and beauty, and Leddy (2012), who argues that we can experience things as having aesthetic qualities without having a full “aesthetic experience.” Leddy (2012) further moves the locus of aesthetic (affective) qualities into the realm of the artwork, which begs the question of what constitutes an aesthetic property or quality of an object. Osborne (1983) and Mitias (1988) similarly attend to the object that is the subject or instigator of the aesthetic experience. They both argue that aesthetic (affective) qualities exist in potential within an artwork, and that an aesthetic experience is the actualization of those qualities (Mitias, 1988; Osborne, 1983). What they fail to account for, however, is the complex background of personal histories, knowledges, and experiences that viewers bring to their art-viewing experiences. Since an experience of viewing cannot exist without both the viewer and the artwork, a conceptualization of the experience that fails to account for the viewer’s unique contributions risks over-simplification. Therefore, affective attributes must be understood—and studied—in the context of object-as-experienced.

While museology, art history, and aesthetics have been interested in theories of aesthetic response, empirical aesthetics focuses on documenting empirical evidence of responses to aesthetic stimuli. However, much of the work of empirical aesthetics focuses on emotional response as opposed to the broader view of affect, as is illustrated by the discussion of “aesthetic emotions,” a term first introduced by Berlyne (1971) and taken up by many contemporary empirical aestheticists (Cupchik, 1995; Elkins, 2004; Leder, 2013; Leder, Markey, & Pelowski, 2015; Pelowski, 2015; Shimamura, 2013; Silvia, 2009, 2010). Aesthetic emotions are emotions that occur in response to aesthetic experiences and are different from “regular” emotions, which are driven by evolutionary factors and needs (Shimamura, 2013). However, debate continues over whether or not aesthetic emotions truly differ in quality or intensity from everyday emotions (see Konecni, 2013, 2015a, 2015b; Leder et al., 2015), although many empirical aestheticists feel that there are nuances to the feelings elicited by aesthetic objects that necessitate unique considerations.

Empirical aestheticists also propose theories of aesthetic experience, most often in the form of models (Armstrong & Detweiler-Bedell, 2008; Cupchik, 1995; Konecni, 2015b; Pelowski, 2015; Scherer, 2005; Schubert, North, & Hargreaves, 2016; Shimamura, 2013; Silvia, 2009, 2010), but these, too, can risk taking a narrowly scoped definition of aesthetic experience. Further, as it is not necessary to explicitly follow a high-level model to conduct research, many other researchers essentially develop models through their research or documentation methods (Bänziger, Grandjean, & Scherer, 2009; Bertola & Patti, 2016; Scherer, 2005; Trohidis, Tsoumakas, Kalliris, & Vlahavas, 2011; Trohidis et al., 2011). The ways that they conceive of aesthetic and affective experiences are reflected in the ways that they seek to study and document them. Regardless of explicit or more subtle model generation and adherence, it is vital to acknowledge a range of aesthetic emotions since art can be experienced in numerous different ways (Leder, 2013).

Affect and Art Museum Information Systems

While object cataloguing has traditionally been the responsibility primarily of registrar departments, significant changes have occurred as collections management software has become more readily available, and as advances in database technologies have resulted in their ability to support the inclusion of multiple forms of knowledge (Parry, 2007). This has led to cataloguing-related activities no longer being solely in the domain of registrars: other information users are now interested in using collections management systems to record information on a variety of collections-related aspects including conservation, exhibition history, and provenance (Coburn & Baca, 2004; Orna & Pettitt, 1998). The collections management system thus has an opportunity to become an aggregation of all relevant information about works in a collection, and, in doing so, become a holistic museum information management system (Weinard, 2015, 2018). In order for this possibility to be realized, the existing data models off of which collections software are based would have to be revised, in order to accommodate new kinds of information and, ideally, types of knowledges and expertise.

A shift from object-centric information models to the development of event-centric information models has become a recurring element of potential solutions to these issues and is a necessary part of the solution to the issue at hand. While object-centric information models centre the object and position other data points as belonging to that object, event-centric models centre an event which then links data points to an object. Since affect in the museum context involves an individual (who is experiencing the affect), an object (the museum object that is the focus or instigator of the experience), and a given context (the exhibition and museum), and is temporally based (the time being the moment of response), an event-centric ontology is necessary to document affective experiences.

The event-centric cultural information data model CIDOC-CRM (http://www.cidoc-crm.org) conceptualizes points of data as outcomes of events: meetings between actors, physical and/or conceptual objects, in places, at times (Doerr, 2003). CIDOC-CRM was also designed to make space for multiple alternative propositions about a given point (Le Boeuf, Doerr, Ore, & Stead, 2017). CIDOC-CRM does not yet have a set of classes and properties to document affective characteristics of viewer-artwork experiences, but its structure makes it a valuable resource for modelling this information.

Although museums are starting to experiment with new collections data models, such as the use of CIDOC-CRM, inherited issues still effect many museum information systems. The information environment created by database systems based on historical practices is insufficient for realizing this potential and supporting a fully documented understanding of a museum object. It is, therefore, essential to create richer systems in order to support contextualization and holistic documentation (Bearman, 2008; Cameron, 2008; Dallas, 1994; Dietz, 1999). Two key components of this re-conceptualization are the adoption of event-centric information systems, and the notion of affect as a means of object knowledge. The space for information afforded by systems that base their structure on legacy practices is not flexible enough to accommodate affective metadata, which is inherently subjective, complex, and multiple—even contradictory—in nature. There do not appear to currently be any museums actively implementing affective metadata, although Williams College Museum of Art has begun exploring the integration of experience data into their collections information (Weinard, 2017, 2018). The importance of affect for museum information also was recently asserted by Krmpotich and Somerville (2016), who studied the absence of affective knowledge in museum information systems, and argue that a catalogue record without affective elements is one that only demonstrates partial knowledge of an object. This assertion succinctly summarizes why it is important to capture affect, and why it is important to include this information within an object information management system: felt aspects are another dimension of what a museum object is, and a system that purports to hold the information that speaks to just that—what an object is—risks trivializing that object when it is limited to holding only certain information, to the detriment of other kinds of knowledge and ways of knowing.

Defining Affect

A key assumption necessary to frame this discussion is that affective attributes are identifiable, and therefore, that there is a consistent definition of what makes an attribute, of an experience or of an object, one of “affect.” For this purpose, I am defining “affect” as a “culturally, socially, and historically constructed category that both encompasses and reaches beyond feelings and emotions” (Cifor, 2016, p. 10). It is “a different kind of intelligence about the world, but it is intelligence none-the-less” (Thrift, 2004, p. 60). Additionally, affect can be a property or attribute that is potential in relation to an artwork. An affective attribute can therefore be thought of as a characteristic of an evocative object (e.g. an artwork), based on the foundational belief that the definition and identity of the object is more than its physical components, but includes its experiential ones as well (Latham, 2007; Leddy, 2012; Mitias, 1988).

Modelling Affective Experiences

Developing an Event-centric Data Model for Affective Experiences in the Art Museum

Incorporating affective metadata into a museum collections information environment involves developing complementary structure and content components. It is necessary to address these aspects together and in an iterative fashion, as each needs to be able to support the work undertaken by the other in order to accurately populate the developed structure.

Structure Standards: The Data Model

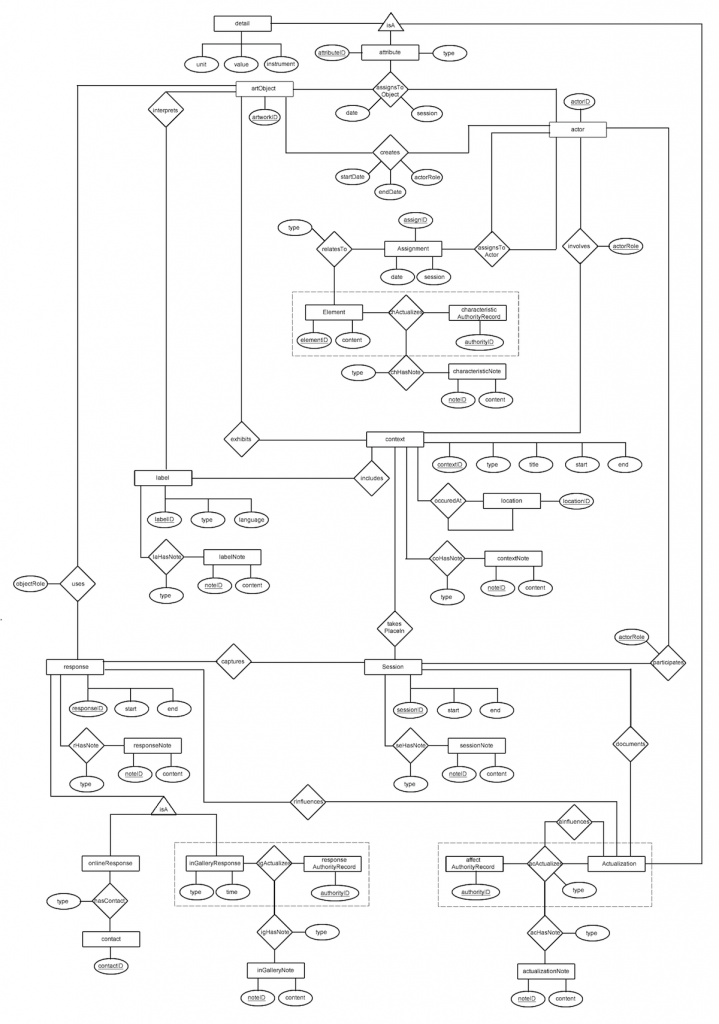

Figure 1: Generic event-centric data model of affective response

The generic event-centric data model, seen above in Figure 1, shows the major entities involved in a researched visitor-object experience and the relationships between them:

- The object, which is the focus or instigator of the experience

- The actor, who has and is involved in an experience

- The context, in which the experience takes place

- The session, in which the affective experiences are observed and recorded

- The response, which is the evidence of the nature of affective experiences

- The actualization, which is the documented affective experience as understood using the supporting content standard

In this model, the actualization of an affective experience is presented as an object attribute. This shows it to be similar to the assertion of other object attributes, such as medium, date, and size. Modelling the actualization this way allows it to be integrated into the information environment in a way that is equal to other points of data; however, while other details maybe modelled as being relatively straightforward (with properties of unit and value), actualization is modelled as the recorded final data point in a process that also involves the actor and context.

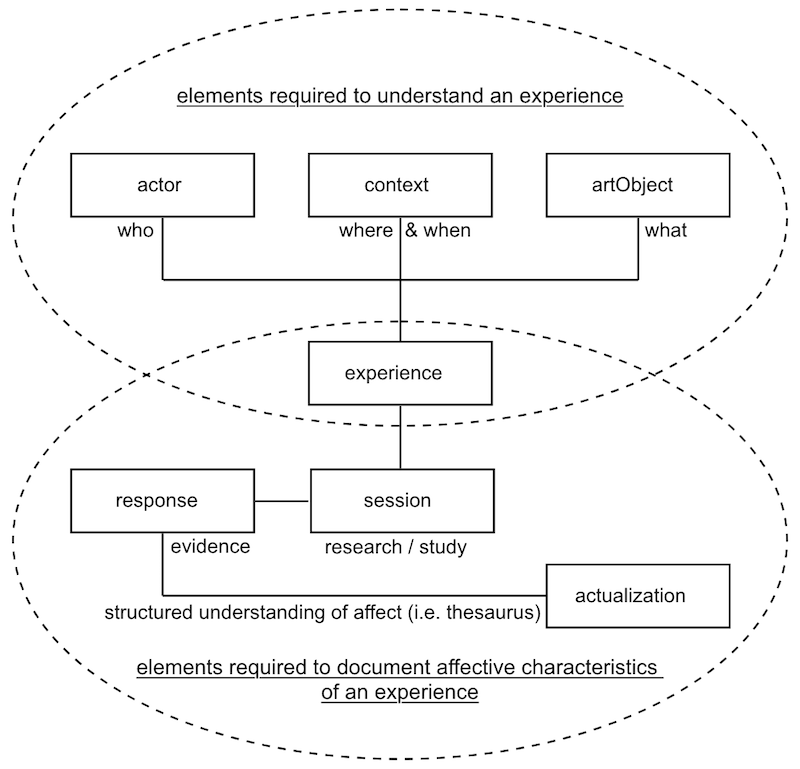

This model expands on the major entities required to understand an experience, and to document the affective attributes of an experience, illustrated below in Figure 2. It simplifies aspects of the object, context, and actor in order to place priority on the modelling of the experience, because this is the newly introduced aspect: event-centric models of people, objects, and contexts already exist—such as CIDOC-CRM.

Figure 2: Simplified model of experience

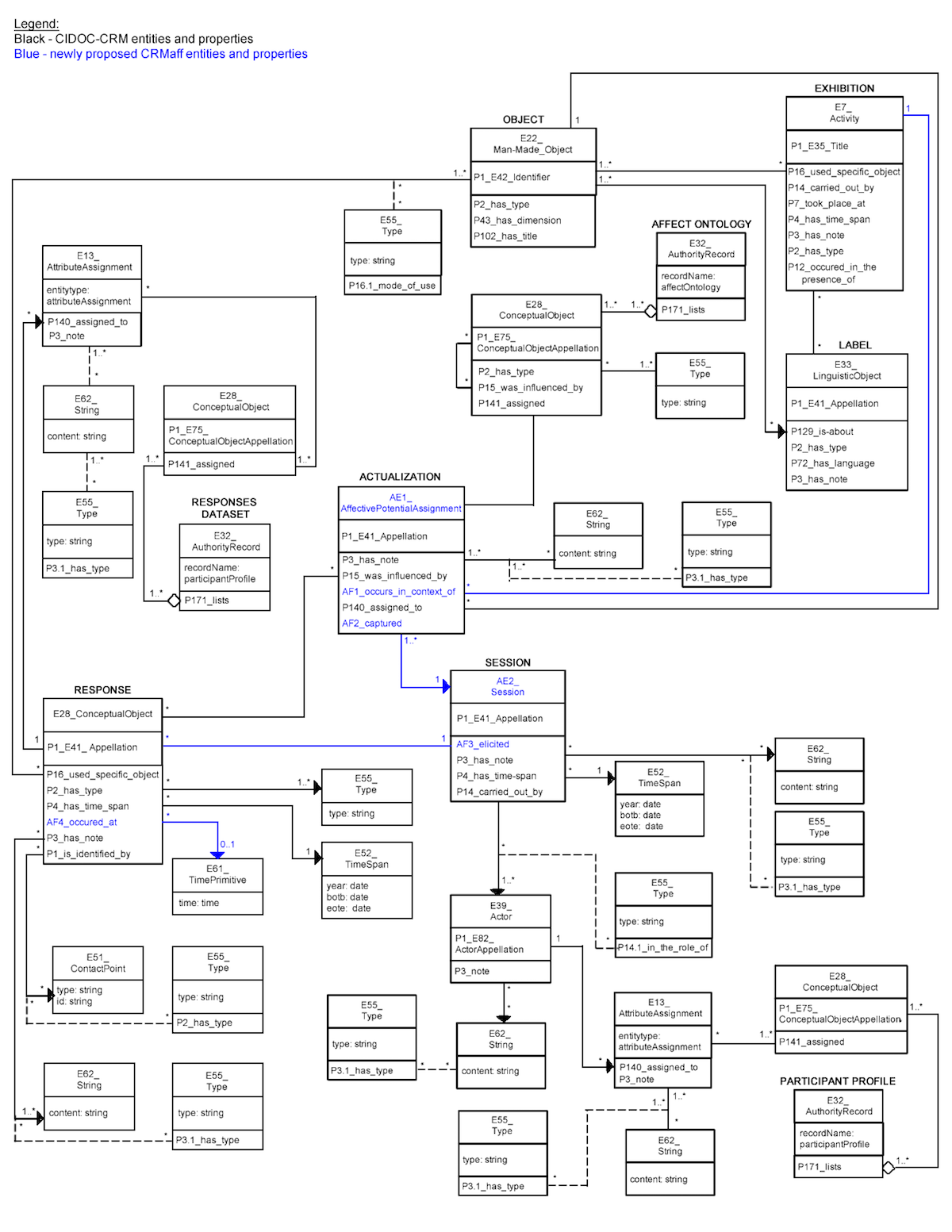

Translating the Model into CIDOC-CRM

This generic event-centric model can be translated into an existing standard, such as CIDOC-CRM, seen below in Figure 3. This allows for the use of supported standards, while highlighting the gaps in existing systems that must be addressed in order for affective metadata to be incorporated. CIDOC-CRM is well positioned to include affective metadata due to its event-centric nature, ability to accommodate multiple and conflicting opinions, and acknowledgement that all information is contextual (Le Boeuf et al., 2017). Full details of the mapping process and proposed CIDOC-CRM extension can be found in Canning (2018b).

Expanding CIDOC-CRM to accommodate affective metadata would involve an extension of two new entities and five new properties:

Additional entities proposed:

- AE1_AffectivePotentialAssignment

Subclass of: E13_AttributeAssignment

Superclass of: None

Properties: AF1_occurs_in _context_of; AF2_captured; properties and references inherited from E13_AttributeAssignment - AE2_Session

Subclass of: E7_Activity

Superclass of: None

Properties: PN2_captured; PN3_elicited; properties and references inherited from E7_Activity

Additional properties proposed:

- AF1_occurs_in_context_of (was_context_to)

Doman: E5_Event

Range: E5_Event - AF2_captured (captured_by)

Domain: AE1_AffectivePotentialAssignment

Range: AE2_Session - AF3_elicited (elicited_by)

Domain: AE2_Session

Range: E28_ConceptualObject - AF4_occurred_at (happened)

Domain: E28_ConceptualObject

Range: E61_TimePrimitive

Figure 3: CRM Data Model

Content Standards: An Affect Thesaurus

In addition to a data model, a taxonomy of affective language (a content standard) is a necessary part of creating affective metadata. Supporting a shared understanding of descriptive terms of affective experiences captured as metadata brings the same advantages to this area of documentation as adherence to shared standards provides for other kinds of data (Baca, Coburn, & Hubbard, 2008; Coburn & Baca, 2004). This is particularly important for this venture because of the nebulous nature of a person describing how they feel—a structured content standard helps to build confidence in that when two instances of the same affective response are documented, they are referring to the same feeling or kind of feeling in as precise a manner as possible. The way that a taxonomy of affective language is structured can help bolster this confidence, providing that it models the terms in a consistent and accurate manner.

The affect thesaurus developed to accompany the data model was built from a literature analysis of affect modelling and the design of ontologies of affect and emotion in the domain of the arts, with a focus on the fields of empirical aesthetics and affective computing. As a result of this analysis, the thesaurus has four key characteristics:

- Prototypical category and term structure: A combination of categorical and dimensional taxonomy structures that allows for individual concepts to have relationships to other terms in the same group or category, as well as relationships between groups or categories at various hierarchical levels (Bänziger, Grandjean, and Scherer, 2009; Liu, et al., 2011; Scherer, 2005; Trohidis, et al., 2011). While categorical structures organize terms into discrete categories, and dimensional structures organize them along dimensions—in this domain, these dimensions are often of valence, falling at a point between the extremes of negativity and positivity, and of arousal, which can be low to high—prototypical structuring is a hybrid of these, combining the two by supporting hierarchical relationships between terms within a category, as well as between categories.

- Poly-hierarchical category structure: A subclass may inherit characteristics from more than one superclass (Bertola & Patti, 2016; Doerr, 2003). In effect, this means that a subcategory of affect may inherit characteristics from more than one broader category, keeping true to the nature of complex feelings: for example, feelings such as curiosity, interest, and wonder can be understood as a type of knowledge emotion as well as a type of epistemic emotion, and thus must inherit from both broader categories.

- Relationships structured as ordinal values: Terms are connected hierarchically but not structured in an absolute scale, as human ratings of emotion do not follow an absolute, consistent scale (Martinez, Yannakakis, & Hallam, 2014).

- Multi-label classification: Any single object may be connected to any number of affective terms from the affect thesaurus, as more than one feeling may be evoked as part of an experience, and thus an accurate model of affect in this context must allow for a single stimulus to belong to multiple categories (Mikels, et al., 2005; Trohidis, et al., 2011).

This thesaurus of elicited aesthetic affective terms encompasses eight major categories—prototypical aesthetic emotions, epistemic emotions, activating feelings, calming feelings, amusement feelings, negative feelings, expertise, and self-reference (association with self and memories)—covering a total 30 categories, with four ranks within each. Each point indicates a different level of intensity of felt experience, as defined by valence, dominance, and arousal. By referring to a given point in this thesaurus, a user can refer to a specific kind or set of affective terms that can show relationships to other terms—such as superclass and sibling classes—through its existence at a given location. Each affective term included has been scaled according to the AFINN ratings of valence value and the valence-arousal-dominance affective ratings provided by the Center for Reading Research (CRR-VAD) (Nielsen, 2011; Warriner, Kuperman, & Brysbaert, 2013).

Integrating the Standards

The affect thesaurus is modeled as an authority record: a standardized form of reference for a domain, in this case, elicited affect. Forming this relationship as a link to an authority record ensures the extendibility of both the data model and affect thesaurus, while promoting clarity of the domain covered by each, and coherence in the relationship between them.

The authority records referenced by the data model are structured with six components:

- Authority Record Name: the name of the authority record

- Domain: the primary level of categorization (multiple domains in one authority record)

- Category: the secondary level of categorization (multiple categories in one domain)

- Intensity: the tertiary level of categorization (multiple intensities in one category)

- Description: the description of the level of the intensity of the category within the domain that is in the given authority record

- Aspect ID: the unique identifier of the point in the authority record being referred to

Validating the Model

The Validation Research

In order to gather a ground-truth dataset with which to validate the model and thesaurus, I engaged in a visitor response study to gather information about affective experiences. My research instruments included a participant profile questionnaire, a field questionnaire, interviews, observational tracking, and physiological feedback in the form of heart-rate variance. Details of research tools and validation study can be found in Canning (2018c).

Developing the Research Tools

The ongoing literature analysis of affect modelling and the design of ontologies of affect and emotion in the domain of the arts provided a grounding for the development of self-response tools. The affect categories proposed by Hagtvedt, et al. (2008), Silvia and Nusbaum (2011), Hager, et al. (2012), and Schindler, et al. (2017) proved to be most useful for the development of the tools, as they provided detailed accounts of their methods, and were focused on measuring elicited affective responses to visual artworks, precisely what the incorporation of affective metadata in this context seeks to cover.

A method of use also accompanies the research tools, in order to define how they are to be used in the research environment. This involves a three-part process to be engaged in following the viewing of an artwork:

- Interview participants about their experiences

- Have participants fill out a Likert-scale questionnaire probing them about their experience

- Interview participants about questionnaire responses

Starting with open-ended, semi-structured interviewing allows participants to begin by describing their experience in their own words, as they perceived it to occur. The questionnaire then provides prompt wording for participants to consider, and a second interview following its completion provides an opportunity for participants to expand upon and clarify the answers given in the questionnaire. Therefore, the questionnaire is not intended to function strictly as a method of quantitative data gathering, but as an aid for participant response.

In addition to self-response methods, the research tools included behaviour observation and tracking and physiological feedback in the form of heart rate variance, captured through use of a FitBit Charge. The inclusion of these additional tools, supports a mixed-methods approach to data gathering, which has been noted as an important consideration for the development of empirical aesthetics research methods (Schindler, et al., 2017). Heart rate variance was selected as the form of physiological feedback for inclusion based on the proposal that it is an indicator of aesthetic-emotional experiences (Grewe, Kopiez, & Altenmüller, 2009; Trondle, Greenwood, Kirchberg, & Tschacher, 2014; Tröndle & Tschacher, 2012). The use of a variety of research tools also supports the exploration of how to model different kinds of documentation: ultimately, the goal of selecting a broad range of methods was to attempt to incorporate a variety of types of data already prevalent in museum visitor studies and empirical aesthetics research, in order to confirm that the data model could accurately integrate this variety.

Conducting the Research

In order to gather a ground-truth data set, a small (n=12) visitor response study on three previously identified artworks (chosen as the result of social media analysis) was conducted at the Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto, Canada) in November 2017 (Canning, 2018a). The three artworks that were selected for the study are:

- The Marchesa Casati, 1919

Augustus Edwin John

oil on canvas

5 x 68.6 cm - Interior with Four Etchings, 1904

Vilhelm Hammershøi

oil on canvas

0 x 51.2 cm - Nude with Clasped Hands, 1905-06

Pablo Picasso

gouache on canvas

5 x 75.6 cm

Validating the Model Against the Acquired Data

The data model and affect thesaurus were first translated into a MySQL environment in order to test the system as a relational database. The data gathered during the research sessions, along with the correspondence between the responses and affective thesaurus identifiers, were then written into this environment.

Discussion

Limitations

The model was validated through a small, proof-of-concept study with a tightly constrained scope. Therefore, the proposal must be understood as having been tested through one-on-one researcher-participant sessions with a small number of participations (n=12), and with a small handful of artworks (n=3) that share similarities in regards to medium, style, and subject.

Findings

Findings in Regard to the Data Model

By working with industry best practices, such as the use of event-centric data models, and providing a holistic data environment that includes both a data model and corresponding knowledge organization system, affective attributes can be structured as metadata so that they can be integrated into a museum object information environment while maintaining the agency of the object, the exhibition context, and the viewer. Furthermore, leveraging already available structures, namely as CIDOC-CRM, suggests a way for existing collections management systems to be augmented so that they experiment with including this information. This proposed data model works to create a richer information environment for objects in the museum collection, as described by Dietz (1999) and Dallas (1994, 2007). It helps bring further understanding to museum objects by placing them within the context of their affective meanings and the roles that they play for museum visitors.

Findings in Regard to the Affect Thesaurus

The responses from the validation study support the structure of affect thesaurus being prototypical, polyhierarchical, with ordinal values, and allowing for multi-label classification. The affective experiences that participants reported involved complexity and contradiction, and were occasionally identity-driven in nature. Furthermore, the responses from the research sessions demonstrate that it is important to include aspects of disinterest, confusion, and negativity— these are also things that happen, and it is essential to make space to capture these reactions. Therefore, a descriptive model of elicited affective response must include all of these facets, or else risk supporting a falsely limited view of aesthetic affective response. The amalgamation of these aspects seems to push the limits of many models of aesthetic emotions, particularly those that seek to address only a limited set of felt reactions as an aesthetic experience. To limit a model of experience to only account for a fraction of responses is an inaccurate model, which only permits space for what the researcher wants to find, as opposed to what is really there.

Findings in Regard to the Research Tools and Methods

The dataset generated from the research sessions shows that affective attributes of artwork-visitor experiences can be discovered through analyzing visitors’ behaviours, talk, and physiological responses. The most robust data came from the interviews in which participants discussed their experiences, both before and after completing the questionnaire. The open-ended interviewing format allowed for a robust exploration of the participants’ reactions and what they meant when they used specific words to describe their experiences, so that questionnaire responses were given greater depth and accuracy of meaning. However, this research did not produce strong evidence of the use of heart rate as a measure of affective response. This may be due to factors such as the small sample size and the use of a commercial wearable, as opposed to a precisely calibrated tool. Lastly, while behaviour did not stand as an independent indicator of affective response, it provided points of confirmation for points brought up in the interviews.

Future Work

Despite the success of the initial findings, there are gaps which remain. The two largest outstanding questions come from opposite ends of consideration: practical applicability and conceptual theory.

Firstly, in order for it to be practical for museums to consider adopting affective metadata, it would be necessary to develop data-gathering techniques and tools that require fewer resources. The research sessions required to gather the dataset were resource-intensive, requiring trained researchers and a considerable time investment. For example, because of the time needed to conduct each research session, it would be nearly impossible to approach visitors in the museum space to participate; participants would need to be pre-selected and know that they were coming to the museum for a research session in order to facilitate the work. Likewise, the work involved in analyzing the responses in order to relate them to affective attributes is time-intensive and requires the skills of a knowledgeable researcher. These are barriers to participation that would need to be significantly lowered in order for sustained research in affective experiences and regular incorporation of affective metadata into the museum information management system to become a possibility.

Secondly, while it is possible to integrate affective responses into this model, it is not entirely possible to incorporate affective experiences that can be understood more as relationships that viewers have with artworks than responses to artworks. This is in part because a relationship involves more complex interactions than a response, which is relatively straightforward in nature. However, it is a challenge that must be addressed. During the validation research sessions, it became clear that not only were participants experiencing elicited affects directly, but that they had affective responses that came as a result of an empathetic connection they were developing between themselves and the artworks by placing themselves in the role of the subject and imagining what it would be like to be that person or in the depicted space. The question remains of how to structure and integrate the complex information about these kinds of empathy-based affective relationships with artworks.

The Question of Empathy: Affect as Relationship, Not Response

The need to address the question of affective experience as a relationship-like responses became clear during the research sessions. Participants reported engaging with artworks using empathy and identity-based connection-making, feeling connected to the depicted subjects, or feeling things on their behalf; they discussed imagining themselves in the place of the subject, what they would feel if they were the subject, or what it would be like to be in the physical or emotional space that the artist depicted the subject as inhabiting. This then influenced their affective responses to the artwork. These kinds of reactions are hinted at by Smith and Campbell (2016) in their discussion of experiences as responses to the human stories embodied within the objects, but go beyond that assertion through the placing of oneself within that imagined embodied space. This presence of empathy in aesthetic response seems indicative of something that is more like an imagined event that links the viewer and a represented entity in an artwork than simply a property or attribute of an affective experience. Therefore, this model needs to have a way to incorporate evidence of empathy, sympathy, and identity-related connections felt by the viewer about, or in connection to, an artwork.

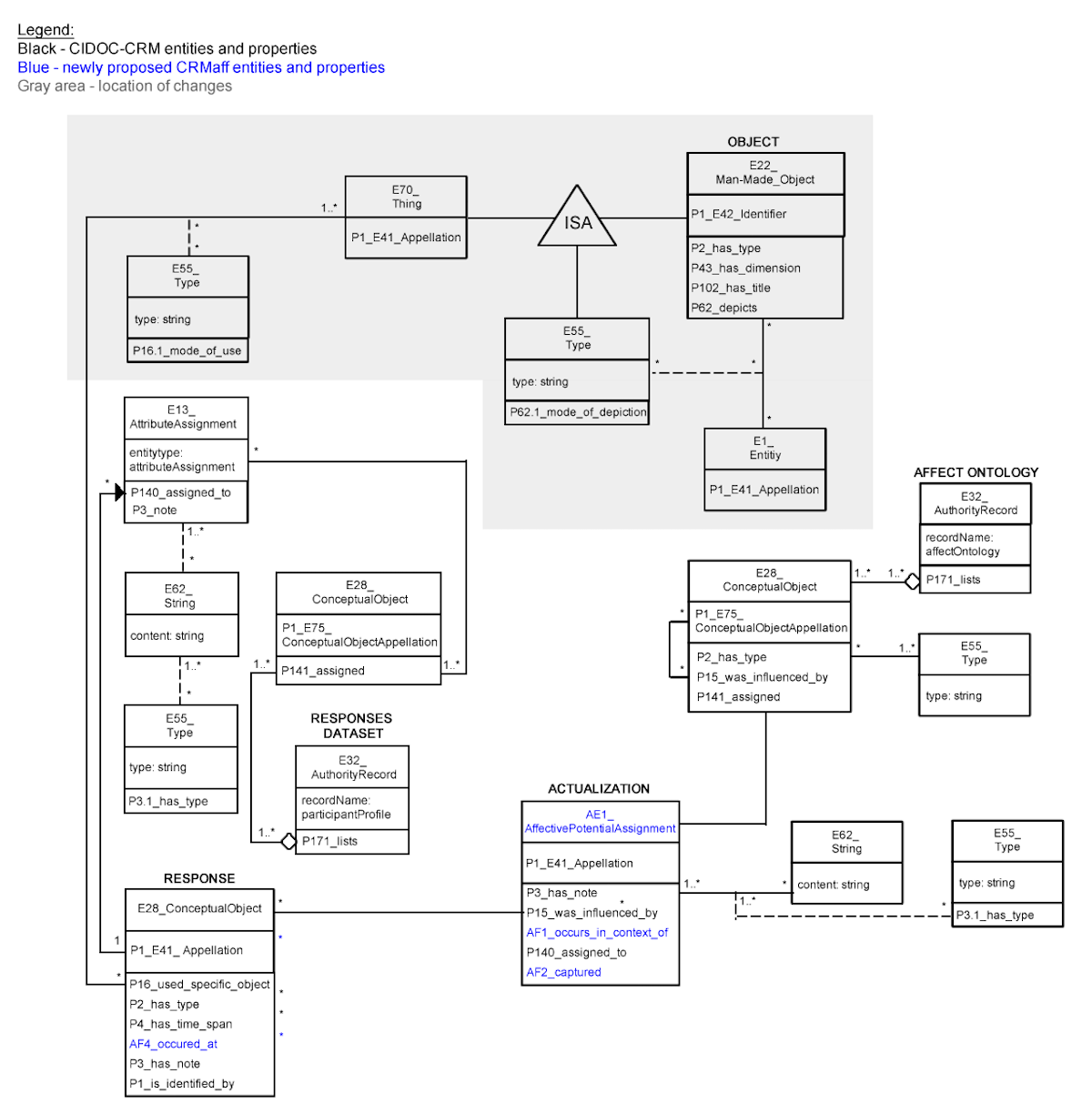

The first step in seeking to accurately represent these elements is creating a path for responses to be mapped to elements of the artwork, and not just the artwork as a whole. To do this, the area of the data model dedicated to the object (E22_ManMadeObject) could be expanded to explicitly reference aspects depicted within the artwork using the P62_depicts (is_depicted_by) property with the supporting subproperty P62.1_mode_of_depiction (E55_Type). The property P16_used_specific_object that links together Responses (instances of E28_ConceptualObject) and artworks (instances of E22_ManMadeObject) could then also be used to link these occurrences of E55_Type with Responses, as P16_used_specific_object takes all Things (entity E70) as its range, which E55_Type falls into. It would not be necessary to model responses to the depicted E1_Entity directly, as the response being captured is not to that entity, but to the depiction of that entity in the artwork that is being responded to. For the MySQL relational database environment, this solution would involve adding a table for E70_Thing for P16_used_specific_object to refer to, to cover instances of both E22_ManMadeObject and E55_Type. By including this option, it is possible to model a response to an entity as depicted in an artwork, as seen below in Figure 4:

Figure 4: Modelling response to elements of an artwork (model excerpt)

The inclusion of this opens up the path for further clarity in the actualization, as not only can the occurrence of once actualization influence another, but the occurrence of an actualization of a response to a particular part of an artwork can be shown to influence the occurrence of an actualization to a different part of the artwork, or the artwork as a whole.

This development takes the next step forward towards modelling empathy and relationship in response, in showing that responses to an aspect an artwork can lead to larger or other affective responses to the artwork as a whole. What this solution does not create space for, though, is the act of imagination, in which the viewer places themselves in the place of the depicted figure. This is a key next step to accurately modelling these more complex kinds of felt responses, and is the next area for investigation in future work. It is essential to treat the modelling and integration of these kinds of responses with care, as they are complex and intersectional, and reducing them simply down to their parts may result in the removal of meaning.

Conclusions

Art museum collections information systems can be more than they currently are. They have the potential to be transformed to support a museum’s mission and practices while also serving as a repository for information—in this case, information about the artwork that goes beyond traditional paradigms. Affective attributes make up a part of what an artwork is and does, and can only be seen through viewers’ experiences with the artwork. By providing a way to structure and represent this information, we can learn more about artworks, and how and why they come to hold places of importance and meaning. Furthermore, this is a technologically feasible initiative: with the inclusion of a small extension of two entities and four properties. CIDOC-CRM is capable of handling the integration of documentation of affective experiences with art objects in the museum setting. The complexities remaining for this knowledge representation challenge come largely from the need to clarify the understanding of how affective experiences to and with art objects occur, and not from technological limitations. With further model refinement and validation, and the consideration of complex, intersectional, and identity-based affective responses, affective metadata and a supporting data model could become a realistic future for object documentation, in which the boundaries of what is thought of as object information worthy of documentation within collections information management systems are expanded and redrawn.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on the thesis, Affective Metadata for Object Experiences in the Art Museum (Canning, 2018a). The author would like to thank all of those who gave their time, wisdom, and expertise to the development of the research on which this paper is based: Dr. Costis Dallas, Dr. Cara Krmpotich, Dr. Sara Perry, and all research participants.

References

Armstrong, T., & Detweiler-Bedell, B. (2008). “Beauty as an emotion: The exhilarating prospect of mastering a challenging world.” Review of General Psychology 12(4), 305–329. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012558

Baca, M., Coburn, E., & Hubbard, S. (2008). “Metadata and Museum Information.” In P. F. Marty & K. B. Jones (ed.). Museum informatics: people, information, and technology in museums. New York: Routledge, 222-234.

Bänziger, T., Grandjean, D., & Scherer, K. R. (2009). “Emotion Recognition From Expressions in Face, Voice, and Body: The Multimodal Emotion Recognition Test (MERT).” Emotion 9(5), 691–704. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017088

Bearman, D. (2008). “Representing Museum Knowledge.” In P. F. Marty & K. B. Jones (ed.). Museum informatics: people, information, and technology in museums. New York: Routledge, 35-57.

Berlyne, D. E. (1971). Aesthetics and psychobiology. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Bertola, F., & Patti, V. (2016). “Ontology-based affective models to organize artworks in the social semantic web.” Information Processing and Management 52(1), 139–162. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2015.10.003

Cameron, F. R. (2008). “Object-oriented democracies: Conceptualising museum collections in networks.” Museum Management and Curatorship 23(3), 229–243. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09647770802233807

Canning, E. (2018a). Affective Metadata for Object Experiences in the Art Museum (MMst thesis). Toronto: University of Toronto. Available at: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/91417/4/Canning_Erin_201811_MMSt_thesis.pdf

Canning, E. (2018b). “Documenting object experiences in the art museum with CIDOC CRM.” In ICOM International Committee for Documentation Conference. Available at: http://network.icom.museum/fileadmin/user_upload/minisites/cidoc/images/CIDOC2018_paper_141.pdf

Canning, E. (2018c, in press). “Evaluating and documenting affect in the art museum.” In 2018 3rd Digital Heritage International Congress (Digital Heritage) held jointly with 2018 24th International Conference on Virtual Systems & Multimedia (VSMM 2018).

Cifor, M. (2016). “Affecting relations: introducing affect theory to archival discourse.” Archival Science 16(1), 7-31. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-015-9261-5

Coburn, E., & Baca, M. (2004). “Beyond the Gallery Walls: Tools and Methods for Leading End-Users to Collections Information.” Bulletin of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 30(5), 14–19. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/bult.323

Cupchik, G. C. (1995). “Emotion in aesthetics: Reactive and reflective models.” Poetics 23(1–2), 177–188. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-422X(94)00014-W

Dallas, C. (1994). “A new agenda for museum information systems.” In Problems and Potentials of Electronic Information in Archaeology. London: British Library, 251-264.

Dallas, C. (2007). “An agency-oriented approach to digital curation theory and practice.” In J. Trant & D. Bearman (eds.). The International Cultural Heritage Informatics Meeting Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Last updated October 24, 2007. Available at: http://www.archimuse.com/ichim07/papers/dallas/dallas.html

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience (Nachdr.). New York: Berkley.

Dietz, S. (1999). “Telling Stories: Procedural Authorship and Extracting Meaning from Museum Databases.” In D. Bearman & J. Trant (eds.). Museums and the Web, 1999: Proceedings. Pittsburgh: Archives & Museum Informatics. Last updated August 15, 2013. Available at: https://www.museumsandtheweb.com/mw99/papers/dietz/dietz.html

Doerr, M. (2003). “The CIDOC Conceptual Reference Module: An Ontological Approach to Semantic Interoperability of Metadata.” AI Magazine 24(3), 75–92. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1609/aimag.v24i3.1720

Elkins, J. (2004). Pictures & tears: a history of people who have cried in front of paintings. New York: Routledge.

Falk, J. H., & Dierking, L. D. (2000). Learning from museums: visitor experiences and the making of meaning. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press.

Grewe, O., Kopiez, R., & Altenmüller, E. (2009). “The chill parameter: Goose bumps and shivers as promising measures in emotion research.” Music Perception 27(1), 61–74. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2009.27.1.61

Hager, M., Hagemann, D., Danner, D., & Schankin, A. (2012). “Assessing aesthetic appreciation of visual artworks—The construction of the Art Reception Survey (ARS).” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 6(4), 320–333. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028776

Hagtvedt, H., Patrick, V. M., & Hagtvedt, R. (2008). “The Perception and Evaluation of Visual Art.” Empirical Studies of the Arts 26(2), 197–218. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2190/EM.26.2.d

Iser, W. (1978). The act of reading: a theory of aesthetic response. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Jauss, H. R. (1982). Toward an aesthetic of reception. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Konecni, V. (2013). “A Critique of Emotivism in Aesthetic Accounts of Visual Art.” Philosophy Today 57(4), 388–400. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5840/philtoday201357433

Konecni, V. (2015a). “Emotion in Painting and Art Installations.” The American Journal of Psychology 128(3), 305–322. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5406/amerjpsyc.128.3.0305

Konecni, V. (2015b). “The Aesthetic Trinity: Awe, Being Moved, Thrills.” Bulletin of Psychology and the Arts 52(2), 27–44. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/e674862010-005

Krmpotich, C., & Somerville, A. (2016). “Affective Presence: The Metonymical Catalogue.” Museum Anthropology 39(2), 178–191. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/muan.12123

Latham, K. F. (2007). “The Poetry of the Museum: A Holistic Model of Numinous Museum Experiences.” Museum Management and Curatorship 22(3), 247–263. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09647770701628594

Latham, K. F. (2012). “Museum object as document: Using Buckland’s information concepts to understand museum experiences.” Journal of Documentation 68(1), 45–71. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/00220411211200329

Le Boeuf, P., Doerr, M., Ore, C. E., & Stead, S. (2017). Definition of the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model. Produced by the ICOM/CIDOC Documentation standards Group, Continued by the CIDOC CRM Special Interest Group. Last updated September 2017. Available at: http://new.cidoc-crm.org/sites/default/files/2017-09-30%23CIDOC%20CRM_v6.2.2_esIP.pdf

Leddy, T. (2012). The extraordinary in the ordinary: the aesthetics of everyday life. Peterborough: Broadview Press.

Leder, H. (2013). “Acknowledging the diversity of aesthetic experiences: Effects of style, meaning, and context.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 36(2), 149–150. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X12001690

Leder, H., Markey, P. S., & Pelowski, M. (2015). “Aesthetic emotions to art—What they are and what makes them special.” Physics of Life Reviews 13, 67–70. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plrev.2015.04.037

Liu, N., Dellandre, E., Tellez, B., & Chen, L. (2011). “Associating textual features with visual ones to improve affective image classification.” In S. D’Mello, A. Graesser, B. Schuller, & J.C. Martin (eds.). ACII’11 Proceedings of the 4th international conference on Affective computing and intelligent interaction Vol. Part I. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg. 195-204. Available at: https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2062805

Martinez, H. P., Yannakakis, G. N., & Hallam, J. (2014). “Don’t Classify Ratings of Affect; Rank Them!” IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 5(3), 314–326. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1109/TAFFC.2014.2352268

Mikels, J. A., Fredrickson, B. L., Larkin, G. R., Lindberg, C. M., Maglio, S. J., & Reuter-Lorenz, P. A. (2005). “Emotional category data on images from the international affective picture system.” Behavior Research Methods 37(4), 626–630. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03192732

Mitias, M. H. (1988). What makes an experience aesthetic? Würzburg: Amsterdam: Königshausen & Neumann; Rodopi.

Nielsen, F. Å. (2011). “A new ANEW: Evaluation of a word list for sentiment analysis in microblogs.” In Proceedings of the ESWC2011 Workshop on “Making Sense of Microposts”: Big Things Come in Small Packages 718, 93–98. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1103.2903

Orna, E., & Pettitt, C. W. (1998). Information management in museums (2nd ed.). Aldershot: Gower.

Osborne, H. (1983). “Expressiveness: Where is the Feeling Found?” The British Journal of Aesthetics 23(2), 122–123. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaesthetics/23.2.112

Parry, R. (2007). Recoding the museum: digital heritage and the technologies of change. London; New York: Routledge.

Pelowski, M. (2015). “Tears and transformation: feeling like crying as an indicator of insightful or ‘aesthetic’ experience with art.” Frontiers in Psychology 6(1006), 1–23. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01006

Scherer, K. R. (2005). “What are emotions? And how can they be measured?” Social Science Information 44(4), 695–729. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018405058216

Schindler, I., Hosoya, G., Menninghaus, W., Beermann, U., Wagner, V., Eid, M., & Scherer, K. R. (2017). “Measuring aesthetic emotions: A review of the literature and a new assessment tool.” PLoS ONE 12(6), e0178899. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178899

Schubert, E., North, A. C., & Hargreaves, D. J. (2016). “Aesthetic Experience Explained by the Affect-Space Framework.” Empirical Musicology Review 11(3–4), 330–345. Available at: http://doi.org/10.18061/emr.v11i3-4.5115

Shimamura, A. P. (2013). Experiencing art: in the brain of the beholder. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

Silvia, P. J. (2009). “Looking past pleasure: Anger, confusion, disgust, pride, surprise, and other unusual aesthetic emotions.” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 3(1), 48–51. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014632

Silvia, P. J. (2010). “Confusion and Interest: The Role of Knowledge Emotions in Aesthetic Experience.” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 4(2), 75–80. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017081

Silvia, P. J., & Nusbaum, E. C. (2011). “On Personality and Piloerection: Individual Differences in Aesthetic Chills and Other Unusual Aesthetic Experiences.” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 5(3), 208–214. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021914

Smith, L., & Campbell, G. (2016). “The Elephant in the Room: Heritage, Affect, and Emotion.” In W. Logan, M. N. Craith, & U. Kockel (eds.). A Companion to Heritage Studies. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 443-460

Thrift, N. (2004). “Intensities of Feeling: Towards a Spatial Politics of Affect.” Geografiska Annaler, Series B: Human Geography 86(1), 57–78. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2004.00154.x

Trohidis, K., Tsoumakas, G., Kalliris, G., & Vlahavas, I. (2011). “Multi-label classification of music by emotion.” EURASIP Journal on Audio, Speech, and Music Processing 1(4). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-4722-2011-426793

Tröndle, M., Greenwood, S., Kirchberg, V., & Tschacher, W. (2014). “An Integrative and Comprehensive Methodology for Studying Aesthetic Experience in the Field: Merging Movement Tracking, Physiology, and Psychological Data.” Environment and Behavior 46(1), 102–135. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916512453839

Tröndle, M., & Tschacher, W. (2012). “The Physiology of Phenomenology: The Effects of Artworks.” Empirical Studies of the Arts 30(1), 75–113 Available at: https://doi.org/10.2190/EM.30.1.g

Warriner, A., Kuperman, V., & Brysbaert, M. (2013). “Norms of valence, arousal, and dominance for 13,915 English lemmas.” Behavior Research Methods 45(4), 1191–1207. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-012-0314-x

Watson, S. (2015). “Emotions in the History Museum.” In A. Witcomb & K. Message (eds.). The International Handbooks of Museum Studies: Museum Theory. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 283-301.

Weinard, C. (2015). “Museums, We Need to Talk.” Medium. Last updated December 3, 2015. Available at: https://medium.com/@caw_/this-is-an-opinionated-love-letter-to-museums-ebe52a726221

Weinard, C. (2017). “New Dimensions for Collections at WCMA.” Medium. Last updated March 20, 2015. Available at: https://medium.com/@caw_/new-dimensions-for-collections-at-wcma-72d4c627fef8

Weinard, C. (2018). “‘Maintaining’ the Future of Museums.” Medium. Last updated December 10, 2018. Available at: https://medium.com/@caw_/maintaining-the-future-of-museums-d72631f6905b

Cite as:

Canning, Erin. "Affect in Information Systems: A Knowledge Organization System Approach to Documenting Visitor-Artwork Experiences." MW19: MW 2019. Published January 15, 2019. Consulted .

https://mw19.mwconf.org/paper/affect-in-information-systems-a-knowledge-organization-system-approach-to-documenting-visitor-artwork-experiences/