Docents and Volunteers: The Audience for Digital Innovation

Karen Voss, J. Paul Getty Museum, USA, Kelly Smith-Fatten, The J. Paul Getty Museum, USA

Abstract

Docents at the Getty Museum and Villa are vital to connecting visitors of all ages to the art and antiquities in our collection. While digital innovations are becoming more prevalent in the museum field, fewer projects have been dedicated to bolster docent and volunteer programs. Over the last year, the Getty produced a responsive mobile website to refresh educational content, automate shift schedules, and provide a dynamic experience so docents can improve what they do in service to the museum. The website provides access to the audio stops, videos, interviews, and various other media that are meaningful to objects in our collection and relevant to the tours docents lead. This presentation will outline the features of this new site and provide a blueprint for others who want to build a dynamic, responsive mobile tool for specific audiences. Building the site required a nimble cross-functional team, and this presentation will detail specific kinds of relationships staff from different parts of the museum needed to establish to produce a site that is compelling and contemporary, innovating with our best educational materials in a responsive mobile atmosphere.Keywords: Museum education, docents, mobile, web site

Introduction: A New Digital Experience for Getty Docents

Docents at the Getty Museum and Villa are deeply connected to our mission of providing free access and education, connecting the public with the collection, and building upon the core values of inclusivity, generosity, and truth. This is in line with many museums’ core goals of providing engaging, educational, and memorable connections with objects in their collections.

In August 2018, the Getty launched the Getty Docent Website, a responsive mobile site to refresh educational content, automate shift schedules, and provide a dynamic experience so docents can improve what they do in service to the museum. After functional requirements were defined, the vendor, Digital Cheetah, built a software plug-in with a secure sign-on, and access to a calendaring system. The vendor’s code was married to a paid WordPress site that allows Getty staff to customize code and update content as needed.

This site is available only to staff and active docents of the Getty Docent Program and is in service to the docents who provide invaluable contributions to the museum every day. This new site was a departure from a previous website utilized by the Getty Docent Program. The old site included program news and events, links to outside resources, object information, and general pedagogical information. However, the site design was outdated: there was not a visual hierarchy for docents to discern the most important information; and while valuable tools were offered on the site, there was not a clear user journey for docents to easily discover them.

Figure 1: The old Getty Docent Website

With this paper, we aim to share the experience of developing and implementing the Getty Docent Website while offering key takeaways that we hope can be useful to the greater museum community. We hope to provide insight for those seeking examples of successful digital endeavors for docents and volunteers. Most importantly, we would like to share the importance of developing the right tools and resources for the specific audience. In our case, the audience—our first and favorite audience—is made up of the docents in the Getty Docent Program.

The Getty Docent Program dates back to 1977 when twenty-six individuals comprised the first class of docents (The Getty Docent Handbook, 2018). As of January, 2019, there are 606 active docents across two sites: The Getty Center in Brentwood and the Getty Villa in Malibu, California.

Getty docents are volunteers who are trained to connect visitors to our collection and the architecture and gardens of both the Getty Center and Getty Villa. They lead tours and offer educational experiences for diverse audiences. Docents are often the first point of contact between visitors and the museum, and therefore serve a crucial role in shaping the museum experience. Site Docents guide visitors on tours about the architecture and gardens at the Villa and Center. School Group Docents primarily utilize the collection in the galleries at each site but may also use the gardens and outdoor spaces to teach Kindergarten through 12th-Grade students who visit the Getty from all over Los Angeles and neighboring counties. Gallery public docents offer tours of the museum’s permanent collection on an ongoing basis, as well as tours of special exhibitions on a regular, rotating schedule.

Because of these differences, docents in each division benefit from tools and resources that are optimized to fit their specific needs and bolster their unique day-to-day activities as volunteers in the Getty Docent Program. Over the course of 17 months (March 2017-August 2018), the Getty Education Department, in collaboration with the Getty Digital Department and an outside vendor, designed, built, and launched a digital environment for docents to access rich resources to support what they do as volunteers.

Throughout research and development, the needs of each division were foregrounded with our guiding principle being that docents are our first and favorite audience. Considering this audience meant that the site would not be built around the needs of the staff who were seeking a desired outcome from docents. Rather, the site would be built around the needs and expectations of the docents first. This idea also served to elevate our thinking around what the end product experience would be: the docents are an audience whose attention we must earn through inspiring content, beautiful images, and elegant design. It is not enough to fulfill objectives for form and function in the new site. We must add value to the docent corps, improve the experience of being a docent, and capture the attention of the audience.

Research on the State of the Field for Digital Tools for Docents

When we began to inch towards prototyping a new site, we researched the “state of the field” of digital tools created specifically for docent populations. We wanted to ensure that we had considered—and adopted—best practices that had been defined or embodied by other museums. This proved a challenge because most museums don’t make their docent materials public-facing. There are practical legal, copyright, and privacy issues that make this the case. Literature on docent training materials was constrained to defining a docent’s role, best teaching practices, guidelines for docents to carry out their work (uniform, shifts, etc.), or how to better serve the public. YouTube contains many introductions to docenting at particular museums and tips for better teaching, but this body of materials tends to comprise outdated institutional messaging that served mainly to recruit docents. While these are valuable first steps, it has been difficult to locate vibrant digital tools made by museums for their docent corps.

We also “took it to the streets” by asking colleagues at other museums to share what they were doing on the digital front. Some institutions had plans to update or create new websites underway. One respondent described their web activity this way:

[Our website] allows us to schedule meetings, keep statistics, archive minutes and hold all the information on tours and artifacts . . . The only websites we are allowed to use for background information are the major museums like the British Museum, the Smithsonian, etc. When we have a special exhibition, the curators provide us with information in the form of catalogues or books. All information is then transferred to our website. All members of the Department of Museum Volunteers (550 members) have access to this information.

Some institutions are testing other tools:

Our museum uses an internal training platform called Litmos, with which we learn and test on different topics, mostly related to IT security. We have been told it has the capacity to let us create syllabi, curriculum, online training resources, communication, video, and testing for docent training. I have suggested we use Google Classroom, but I’ve been asked to give Litmos a fair try first, which I will. Jury is still out on this endeavor.

We will continue to survey the field, and welcome any leads to museums that are actively creating innovative digital tools for docents.

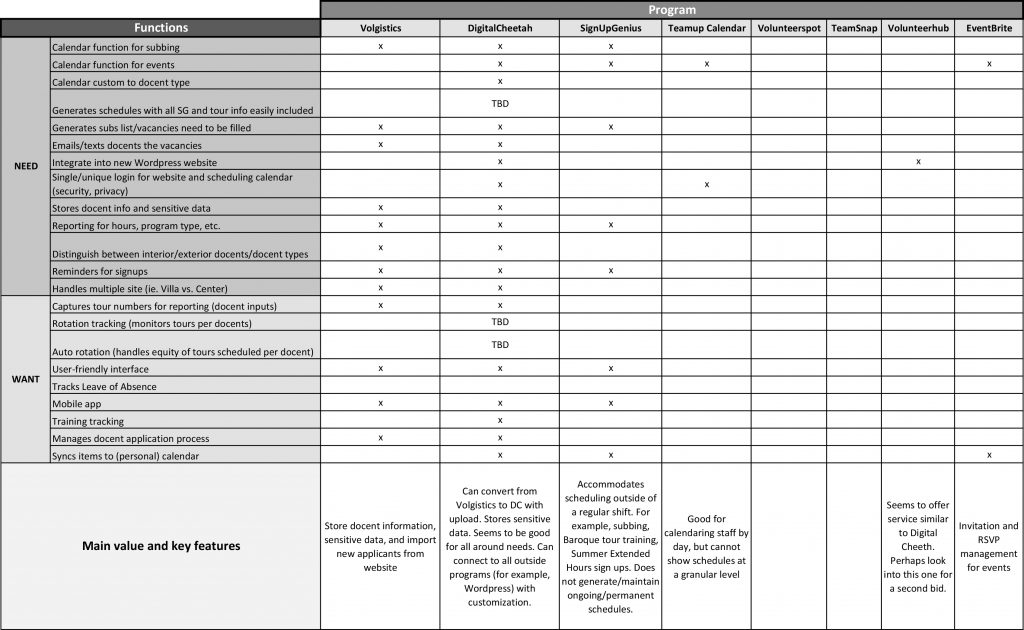

During the research phase for digital scheduling systems specifically, six cultural institutions of similar size across the United States were queried directly, along with two volunteer organizations with larger volunteer corps than the Getty. Several more institutions shared information about the scheduling technology used by responding to general inquiries posted to a digital message board. Volgistics is an online scheduling tool used by several of the museums approached, and was the primary tool used by the Getty Docent Program for housing docent data. Some institutions queried used antiquated systems including one museum in the Los Angeles area which used a DOS program to schedule group reservations. Docents then sign up to lead those tours by writing their names in a book located at the museum itself. Each institution queried had different needs and systems built to meet their needs, whether manual or digital. The one thing in common was the desire to have more sophisticated technology to make their jobs easier and to provide a better experience for docents and volunteers, and by extension, a better experience for the visitors.

Ultimately, we settled on a vendor, Digital Cheetah, because they offered the most features we determined would be required as well as the option to customize the website/scheduling experience.

Figure 2: Programs assessed for scheduling value

Assessing Content, Design, and Functionality

Moving our educational tools online meant first assessing the value of existing materials, as well as “translating” internal acronyms to a cross-functional team, including media producers, web designers, developers, and vendors. Research materials—the “Red Files” and the MOWs (Masterpiece of the Week)—needed to be re-evaluated, refreshed, and understood beyond the docent team. Hundreds of Red Files (photocopied materials in red file folders) included printed images, presentations, articles, essays, book chapters, object provenances, notes from curators, press, and other “exotica,” depending on how old the files were. Any institution wanting to revisit and renew their docent materials should first consider what needs to be updated and how to plan for future cycles of updating. Understanding docent materials as living, growing things that need continual tending requires commitment.

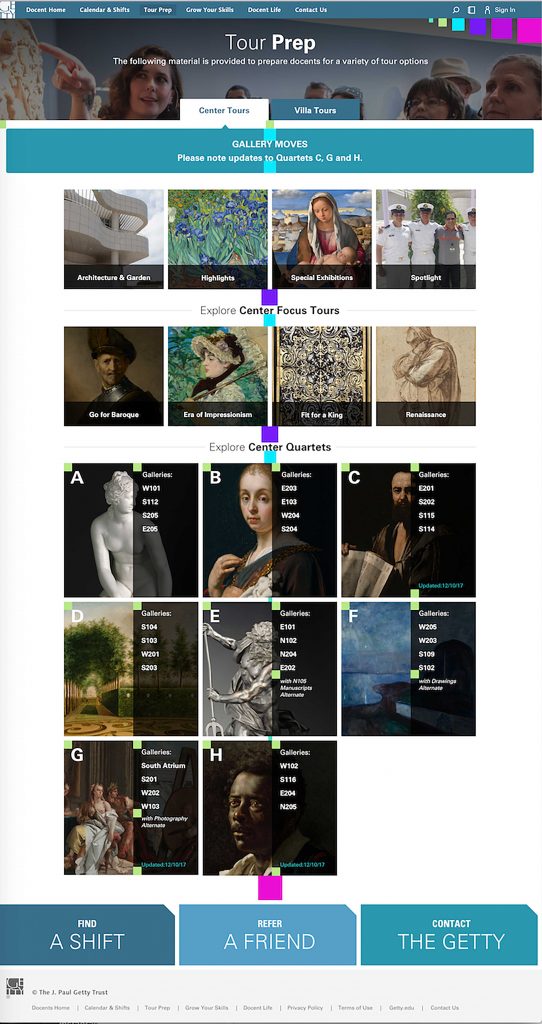

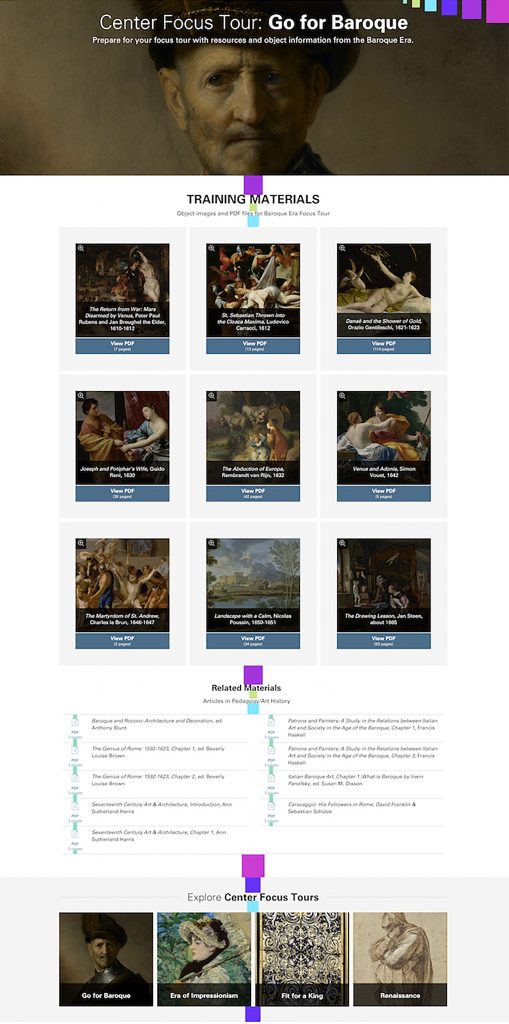

Themed tours such as “Go for Baroque” or the “Era of Impressionism” included tailored materials to teaching about the Getty’s objects that fell within the realm of those overarching ideas. We also had materials for “Architecture” and “Garden” tours. But we also had what we call the “quartets,” a complicated system of providing materials on objects from sets of four galleries that docents would address in a specific day. Each gallery included a number of objects, and providing materials on each allowed docents options as to which specific objects they could teach with on a given tour. The Center housed eight quartets and the Villa housed sixteen. We also provided rotating information on “Masterpieces of the Week,” Spotlight pieces, and materials for new exhibitions.

Over the years, a trove of training materials, resources on pedagogy, and internal scholarship accumulated. We had mammoth amounts of paper materials that docents were welcome to use. And they did use them. Docents carried around huge binders with hundreds of pages of photocopied materials; nobody complained, but we asked ourselves, was this going to be our only delivery method as our docent population became more literate with digital platforms? Ultimately, we determined that these documents would need to be digitized as the standard for the future of the Getty Docent Program so they could access key materials anywhere with their own devices.

Gallery Educators spent weeks reviewing the “Red Files.” Another team combed through the files on the outdated docent website. Still, another staff member looked outside of what the Docent Program and Education teams had been collecting over the years for docents to use as resources and searched the Getty YouTube and public-facing website for relevant materials that could be linked up with the docent website. While the museum regularly produced audio and video content, it wasn’t married to the resources in the paper files, an issue we wanted to resolve in the new website.

As we determined what to keep for the new website, we used the following criteria:

● Relevant: Everything that would be translated into digital format would need to be relevant to the teaching that docents are expected to do now. Outdated or tangential materials would be filtered out.

● Designed: All documents and teaching materials needed consistent formatting and design to form a cohesive brand.

● Accessible and On-Demand: To meet the needs of our current docents while transitioning to a digital future, materials could still be downloaded and printed. All materials should be “findable” through a robust keyword search function built into the site.

● Within a Defined Scope: Though the desire to provide encyclopedic materials was strong, we needed to clarify which materials were essential. We would not repeat information already available on Getty.edu.

Copyright concerns are inherent when providing articles and excerpts from publications, along with images from the collection or loans. Museum legal teams should be partnered early on in the process to provide guidance on how to properly present materials. Getty council advised our team to provide full citations along with copyright on all materials we provide to docents. Legal also weighed in on the top privacy issues concerning docents’ personal information before we populated the new system with data.

In addition to reviewing existing materials, the scheduling system—Excel sheets and clipboards—needed to be understood by the whole team. Because we yearned for an automated scheduling system to benefit the docent experience, the intricacies of how certain types of docents were scheduled on shifts needed to be explained to our developers.

The Dream

We aspired to a sophisticated functionality that would allow us to provide all of our updated materials, automate the scheduling system, and allow for audio, video, and gallery pages that correspond to docent tours. We wanted the site to be responsive on mobile, and we wanted it to be beautiful.

Ideally, the new system would allow a greater ease for docents to find their schedules, sign up for continuing education and community events, and discover tools and research materials to support their teaching. New docents in training would access their syllabus and reading assignments, as the site would become a key tool in their training program. All materials are centralized and available from any location, provided the docent has Internet access. For staff, scheduling would be dynamic and digital (rather than static and manual), notifications for shift openings would be automated, and docent data would be easily referenced in one system. Both staff and docents would benefit from a secure system that utilizes password protection and levels of administrative access based on assigned permissions: Every docent would have their own unique login and profile within the system, only a limited amount of docent data would be collected and available for sharing, and only designated staff members could access sensitive information.

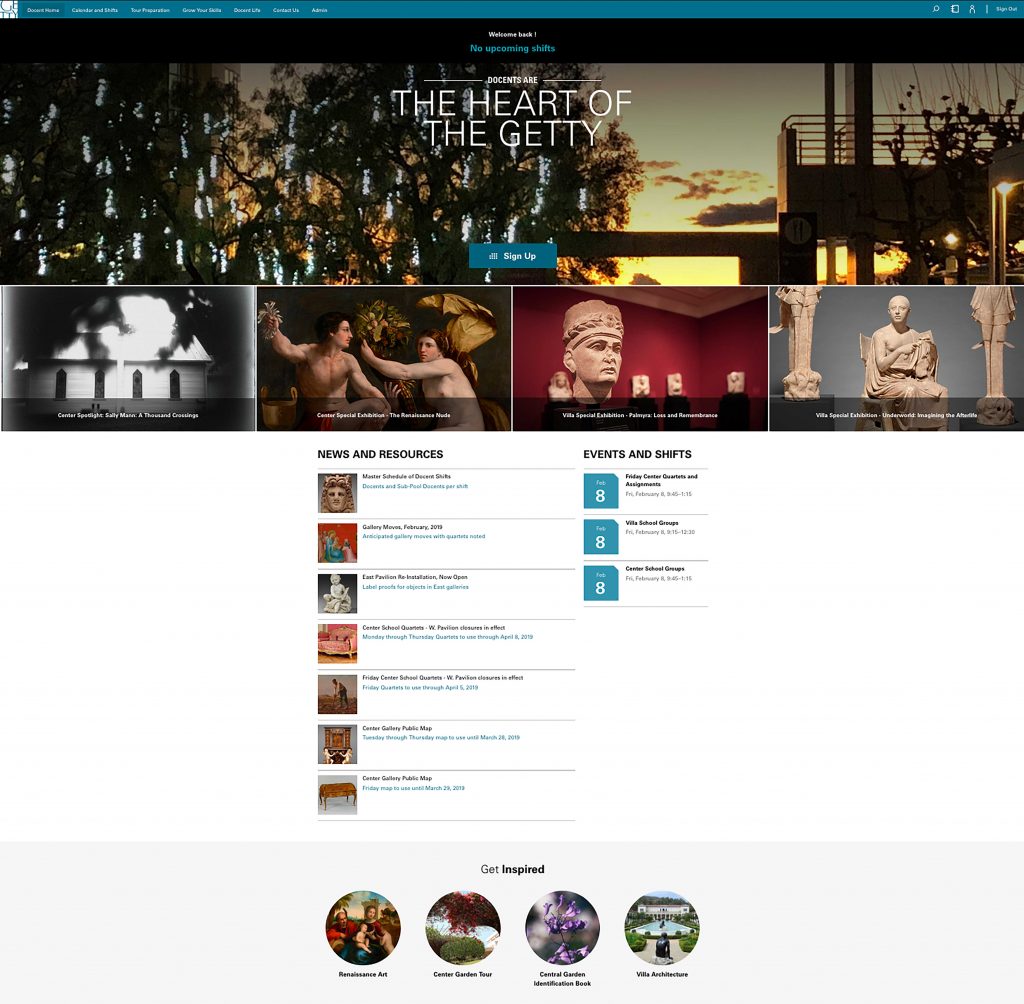

Additionally, the docent website would serve to bolster a sense of community and unity across the six divisions of the corps. The new website would become a streamlined way for staff to communicate a uniform message to docents that is welcoming and inspiring. The homepage would feature only the most optimistic images, and eventually the message “Docents are the heart of the Getty” would be incorporated into the design of the homepage. The homepage experience is personalized so that the docent’s name appears at the top of the page along with their next shift date listed. Importantly, all docents can access all resources on the site. The design would be such that, even while a docent would encounter personalization upon login to the homepage, that docent could choose to explore any area of the site. For example, a Center Gallery public docent would see their name and upcoming shift at the top of the page upon login. Towards the middle of the page, in a section called “Events and Shifts” only Center Gallery public events and shifts would bubble up from the calendar via a custom dynamic feed. Also on the homepage, however, are featured links for Villa Gallery public educational materials such as those a Villa docent might use to prepare to teach a special exhibition tour. Our hypothetical Center docent may choose to explore that link in addition to any other Center or Villa-specific links available on the homepage or elsewhere on the site. This experience would allow each docent-type to find the most important information he or she is seeking, and at the same time experience a sense of community and unity across the Program.

Figure 3: The new docent site home page

The Build

In the ensuing months (March 2017-August 2018), the build of the site happened in fluid phases. For the sake of this paper, we have organized our process into distinct phases, though the reality was much more porous.

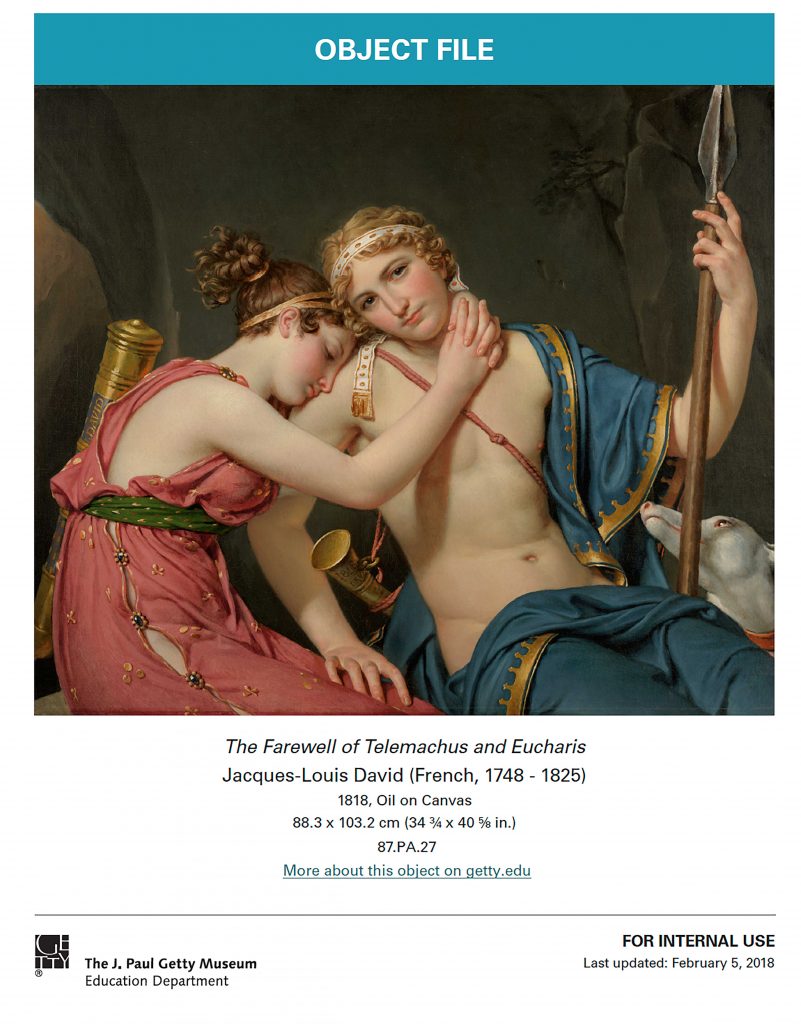

In the first phase, a cross-functional team was assembled, and a series of translations occurred. The education team’s expertise in docent materials, training, and teaching methods needed to be translated to the digital team. Conversely, the digital team had to teach the education team what was meant by “content” and “assets,” as well as how to draw up instructions for loading said content and assets appropriately onto a page. Months were needed to communicate what all the docent materials were for and how to organize and prioritize them into wireframes—diagrams of the structure and functionality of the intended site. Getty Digital’s expertise in user design, functionality, and development skills led to a series of negotiations. If, for example, we were going to make our object files completely dynamic, we would need a vast amount of time to recast the paper materials into a digital experience. While the object files had been filtered for outdated materials, the bulk of the materials could not be reconfigured in dynamic pages if we were to finish the site in a year. So, we compromised. Object files would be scanned into PDFs with each article, book chapter, related media, etc., assembled under a dynamic table of contents. Docents could jump to any portion of the file either by clicking on items in the table of contents or by using the bookmarks.

Figure 4: New digital object file cover

Terminology was also debated. What, for example, would docents expect a “pedagogy” tab to link to? How could we divide school group materials from those for gallery public tours at the Getty and the Villa without ending up with an undifferentiated hunk? Using design-thinking methods and card sorting techniques, we hammered out a structure and hierarchy for the site that we felt met both docents’ key needs and a significant improvement over what we had before. Journey mapping also played a role in initial prototyping. What would docent A, for example, expect the menu headings to unveil? Which items would they most seek? The team worked to map out these journeys so that docents would be able to find what they needed in the least amount of clicks possible.

Though the desire to stream video was strong, the options of embedding, streaming, or linking (say to YouTube, for example) required a great deal of resources we simply did not have. Copyright and legal issues also came into play, because a fair amount of our video was meant for internal use only, which made linking to YouTube or an external site problematic. We did discover some ways to jerry-rig our WordPress template to include some video links, but it was not going to be feasible or cinematic on a long-term basis.

We desired two components for the scheduling system: The first part would be the calendar where docents can register and unregister for shifts and events that are relevant to their particular docent division. This feature is part of Digital Cheetah’s core product and would provide the additional functionalities needed, such as notifying docents of openings in shifts automatically. The second part would be a daily schedule view customized by the vendor, based upon our design specifications. Ideally, a docent could click on their daily schedule to see what specific tours they would be assigned to lead that day. A site docent, for example, would be able to see graphically that they would lead an architecture tour at 10:30 followed by a break, then a garden tour at 12:30.

A fair amount of time was spent to hone the intricacies of the scheduling system digitally. While the functioning of the docent schedules were understood conceptually, an additional challenge came about as to how the vendor would code the requirements of the schedules that previously had been managed manually by the Docent Program staff. For example, if a docent rotates through quartets monthly, how would that logic be set in code and represented visually? How do docents rotate through tour schedules to ensure they get a variety of tour types each time they volunteer? All of this had to be flushed out conceptually and in code because the quality of the docent experience depended on it. One of the most sought-after pieces of information by docents in the Getty Docent Program is, “what is my schedule and what tours am I expected to lead?”

Phase two involved producing design comps to establish the aesthetic theme and a wireframe of the site. Once again, this required vivid negotiation. What a “beautiful” website would actually look like needed to be vetted by numerous stakeholders. Actual details like image resolution and zooming capabilities had to be worked out. We also needed to list every page that needed building, along with the degree of functionality. The education team was ready and willing to move outside their comfort zone to gain more fluency with the digital components, but some anxiety lingered. As museums’ web sites grow more sophisticated, particularly when it comes to educational or docent-oriented sites, a real consensus needs to grow around the degrees to which educators should be digitally literate, and the degrees to which the web development team needs to become subject-matter experts. Some contributors need to have their feet in both worlds. We see this as crucial terrain to work through as museums make more digital projects.

Figures 5: Design comps that were approved

Figures 6: Design comps that were approved

Once the design look, the website structure, and the degree of functionality were finalized and approved, phase three began: the actual building. WordPress pages were designed to accommodate different media needs. Extra staff were trained in uploading content into the WordPress content management system and then linking materials to the correct areas. We found that certain staff members took the technical shuffling with ease, while others did not enjoy building a new skill set above and beyond their normal roles and responsibilities. But as the intended launch date approached, it became an “all-hands-on-deck” climate. Of great importance is managing group dynamics and institutional idiosyncrasies. Museums aren’t necessarily structured to properly project manage websites at more complex levels, but this is perhaps something our field should confront.

Throughout the research and build, the Getty digital team investigated whether or not the new site would be entirely or partially hosted by Digital Cheetah. In the end, it was decided that the WordPress component would be Getty-hosted and housed within our existing digital infrastructure, while Digital Cheetah would continue to host the core product functionalities. It is worth noting that the Getty team did look into the data security of the vendor, and it was determined that the system would meet our needs. Museums should make data security a priority now and in the future.

Another key aspect to building complex digital projects is allowing enough time for proper user testing and quality assurance across devices, platforms, and browsers. Even though our web designer provided exquisite fonts and image specifications using industry-standard technology, not all of the education staff were on Apple computers, meaning some could not view the file type. Nor did they necessarily have Photoshop for simple cropping of images. In the end, sexy fonts had to be changed to Arial because it wasn’t licensed for every Getty computer.

We have experienced bugs and shortcomings within the current design and coding of the site. However, this is interpreted as part of the ongoing process of upgrading and improving the design. Our teams are now identifying the most important aspects to address in the coming months for the next phase.

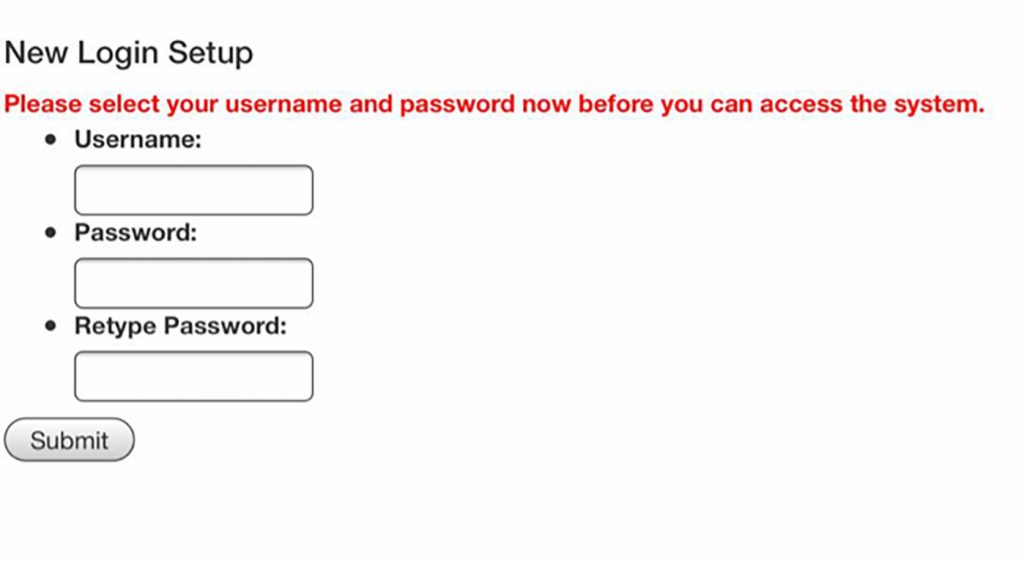

One set of “bugs” that we are still in the process of improving concerns the initial login and username/password recovery experience. Currently, the sign on process functions as it should on the software level, successfully passing one set of credentials through to both the WordPress and Digital Cheetah environments. The result is that the end user needs only to remember one login and does not perceive a delineation between the two digital worlds that have been tied together by a custom-built software plugin. Shortly after launch, we learned that some docents were having trouble logging in. The very first time a docent logs on to the website, the docent receives an invitation link, clicks on it, and is redirected to a page where they are prompted to create a username and password. The system requires a strong password containing at least eight characters including uppercase, lowercase, numbers, and symbols, though it is not indicated anywhere on the page. The result has been that a swath of docents have been confused on how to complete the username/password set up, had their passwords rejected, and in some cases, have failed to move past this step and were effectively deterred from using the website altogether.

Figure 7: Landing page for initial username and password set up

Docents attempting to recover lost login information may have a similar experience in that instructions for the mandatory credential features are not included on the reset password pages. Nor is there a mechanism to determine whether or not the username entered by the docent is incorrect, and it cannot be reset until the docent is logged in.

The solution to these issues will include a redesign of the username/password set-up and reset landing pages, along with the coding of a mechanism by which to recover lost usernames. An important lesson is learned that every detail about the pre-login and login experience counts to the extent that it can make or break the success of the website. After all, how can our first and favorite audience reap the benefits of the tools and resources we are offering, if they cannot get past the gates?

Post-launch Assessment and Planning for the Future

Websites are “living” in that they need maintenance and care in order to continue to serve their audience optimally. We see the Getty Docent Website as iterative: an ongoing project with many opportunities to listen to the audience and improve upon existing features.

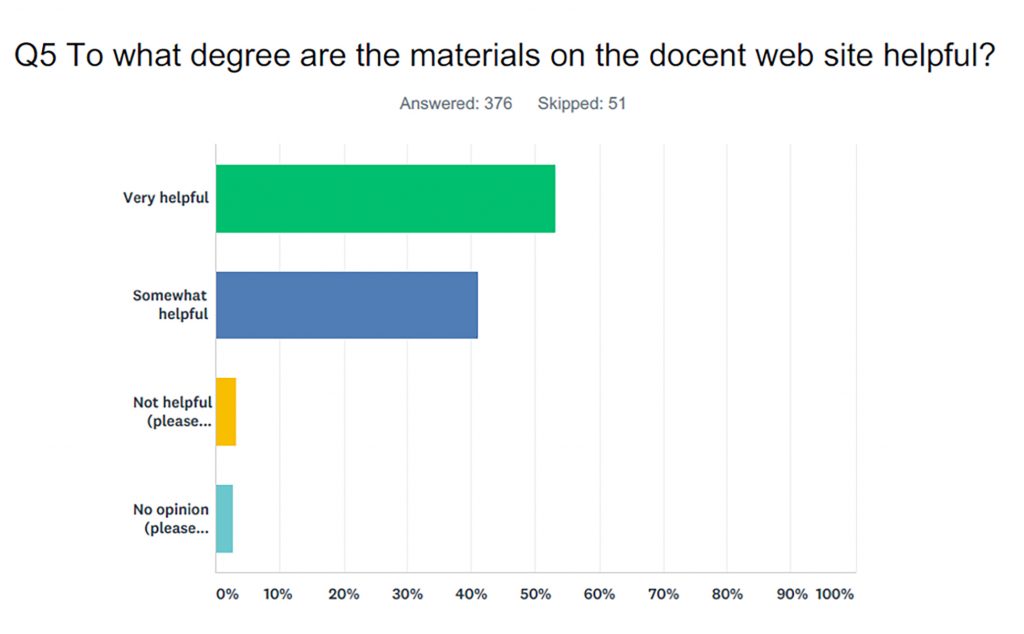

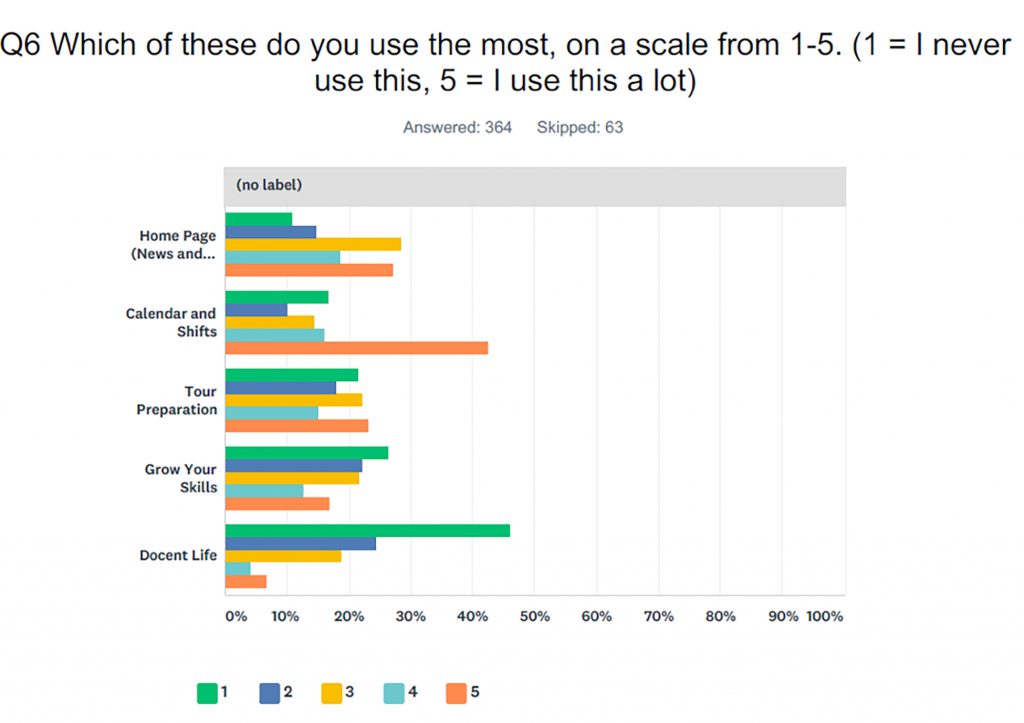

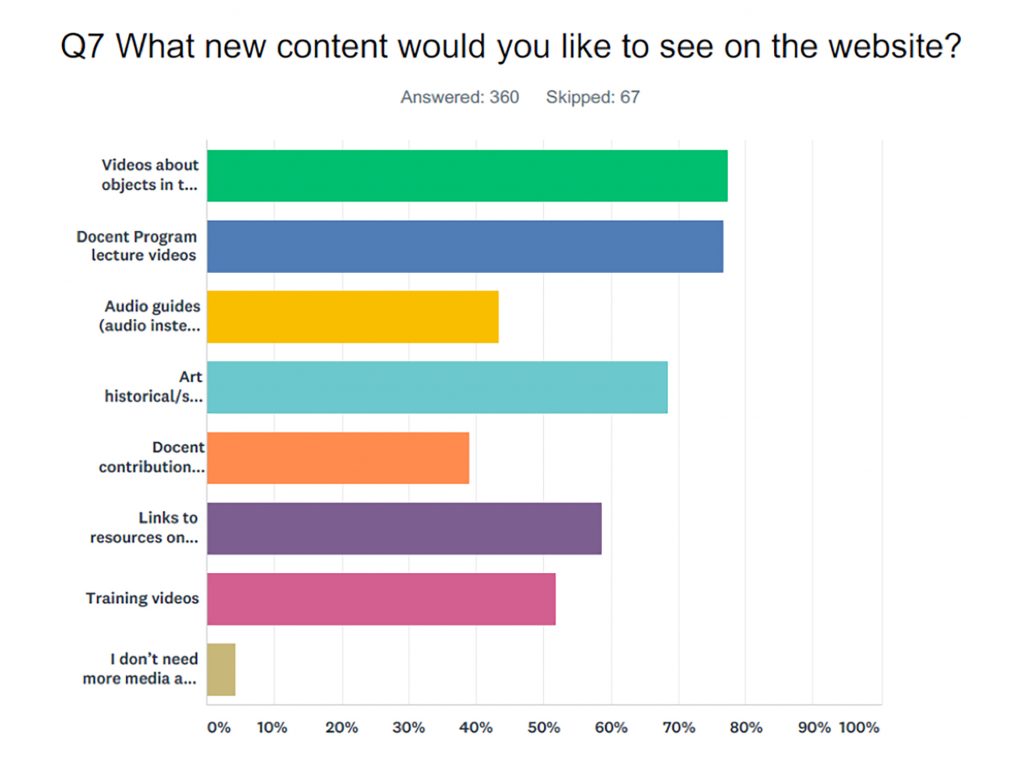

After the site had been launched and live for three months, our team designed a survey using SurveyMonkey to learn how docents had been using it thus far, as well as to discover our next steps to improving the site. The survey ran from November 27 to December 9, 2018, and captured the responses of 427 docents, or about 70% of the Getty’s total docent corps. Eleven questions were crafted to capture responses ranging from whether docents have been able to login successfully and consistently (71.13% of respondents said, yes), to the type of device they prefer when visiting the site (76.23% prefer desktops), and what new content would docents like to see.

While this first survey is broad, successive surveys can focus on questions regarding specific resources we plan to create. For example, in the chart below, the docent respondents are nearly tied in favoring videos about objects in the Getty collection and docent program lecture videos (lectures by Getty curators and other special guests specifically for docents). A next survey could include questions about which area of the collection, Baroque or Antiquity for example, would it be most helpful to focus our video-making efforts.

Important key findings from our first Docent Website survey are included below.

Figures 8, 9 and 10: Charts from the Getty Docent Website Feedback Survey, November 27 through December 9, 2018. Data represents responses from 427 docents, or approximately 70% of the Getty docent corps.

Going forward, our team plans to employ focus groups with docents to find out what they want and need. As we continue to improve the site, it will be important to maintain the guiding principle that docents are our first and favorite audience, discovering what docents would find valuable versus what staff thinks they would find valuable. Prior to launch we shared versions of the site with docents from the Getty Docent Leadership Team (DLT), a staff advisory board made up of docents from each of the Docent Program divisions. Non-DLT Docents joined a DLT committee and convened for the purpose of reviewing the site, identifying issues, and offering feedback. In the future, these committees could be expanded to include greater numbers of docents.

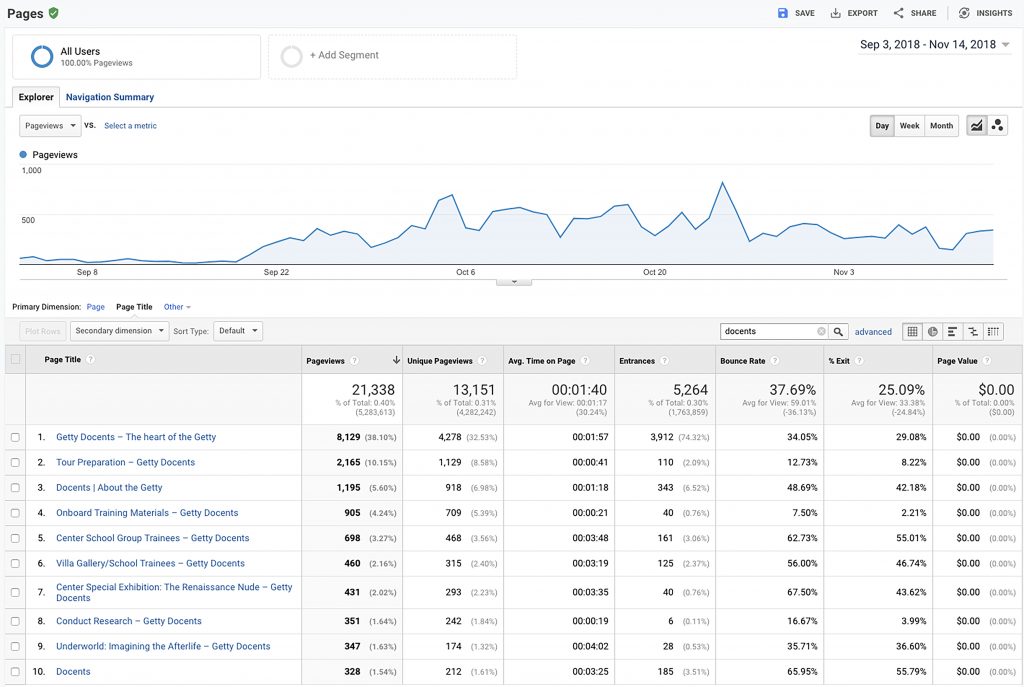

Google Analytics is another tool we are using to track usage and determine which pages are most visited. Along with qualitative measurements from our first and ongoing surveys, we can begin to identify the successes and failures of the Docent Website. Our gauge of success will revolve around whether or not docents continue to access the site easily and often, and find the content relevant and helpful.

Figure 11: Google Analytics snapshot

Throughout this process it became clear that simply re-doing the website was not the end goal. It was a step to inform the next version of the website. And for institutions more broadly, we should not merely be creating digital tools, but preparing for their obsolescence. How do we accept and accommodate the fact that we will always have to renew our digital materials and grow as new devices and platforms arise?

Conclusion

Innovating digital tools for our docent communities as a field is still in its infancy, and institutions with dramatically different access to funding and resources may not be at a place where they can create more sophisticated digital content. Nevertheless, it is crucial to build consensus within each institution as to how the future of docent materials will take shape. Our own foray showed us how outdated our materials were, how crisscrossing skill sets needed to be built within the institution, and how testing, maintenance, and analytics remain crucial to assessing the value of our efforts. With the right tools and resources for docent and volunteer audiences, we believe such endeavors will ultimately add value to the museum community overall.

References

Anderson, K. (2009). “A World of Digital Docents.” The Scholarly Kitchen. https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2009/05/18/a-world-of-digital-docents/

Burnham, R & Kai-Kee, E. (2014). Teaching in the Art Museum: Interpretation as Experience. The J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles, California.

Falk, J. & Dierking, L. (2013). The Museum Experience Revisited. Left Coast Press, Inc. Walnut Creek, California.

Fernández-Keys, A. (2010). “Caught in the Middle: Thoughts and Observations on the Information Needs of Art Museum Docents.” Art Libraries Society of North America, Vol. 29, No.2. Chicago, Illinois.

J. Paul Getty Trust. (2018). The Getty Docent Handbook.

Katz, J., LaBar, W., & Lynch, E, editors. (2011). “Creativity and Technology: Social Media, Mobiles and Museums.” MuseumsEtc Ltd. Edinburgh, United Kingdom.

Sayre, S. & Wetterlund, K. (2008). “The Social Life of Technology for Museum Visitors.” Visual Arts Research, Vol. 34, No.2. University of Illinois Press. Chicago, Illinois.

Cite as:

Voss, Karen and Smith-Fatten, Kelly. "Docents and Volunteers: The Audience for Digital Innovation." MW19: MW 2019. Published January 16, 2019. Consulted .

https://mw19.mwconf.org/paper/docents-and-volunteers-the-audience-for-digital-innovation/