Mapping Space, Time, and the Collection at SFO Museum

Aaron Cope, SFO Museum, USA

Abstract

This presentation will discuss work modeling and marrying the San Francisco International Airport (SFO) Museum collection and the airport itself, with the Who's On First (WOF) gazetteer of geographic places, producing an openly licensed data set native to the web and existing geographic information systems (GIS), that we are using this data to build and power our own online efforts. This paper and presentation will discuss the motivations behind the project, why our approach is necessary and beneficial in the historical context of digital initiatives in the museum sector, the lessons learned so far, and how we see this work as the core scaffolding for the museum's digital efforts going forward.Keywords: Geography, Open Data, Airports, History, Mapping

Introduction

The SFO Museum (https://sfomuseum.org/) is a fully accredited museum that has operated inside and as part of the San Francisco International Airport (https://flysfo.com/) (SFO) since 1980. The airport is owned and operated by the City and County of San Francisco (https://sfgov.org/). SFO Museum consists of a permanent aviation collection, with a focus on “the history of commercial air transport, the airline industry, and San Francisco International Airport with a regional emphasis on the West Coast and the Pacific Rim,” an aviation library and archive. There is also as an active program of curated temporary exhibitions (on average 30-40 annually) consisting of a mix of objects from the permanent collection and loan objects from private lenders and other cultural heritage institutions. Additionally, SFO Museum oversees the public art works, purchased by the San Francisco Arts Commission (SFAC), on display at the airport. In 2017, 55 million passengers flew in or out of SFO.

A museum, with both temporary and permanent collections, is distinct from a library as both are from an archive. Each represents a unique areas of focus, expertise, and responsibility, and they carry important and meaningful distinctions to people who work in the cultural heritage sector. The same can’t be said, or assumed, of people not working in the cultural heritage sector so for the purposes of this paper, when I discuss “the collection,” I am talking about everything that SFO Museum does, everything it produces, everything it cares for.

Starting in early 2018, SFO Museum secured funding for full-time staff to pursue digital initiatives around the museum’s collection and exhibitions history (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/about). This paper documents those efforts to date. The goal of this work can be summarized as follows:

To ensure that every aspect of a trip to SFO, and every facet of someone’s time spent in the airport whether they are arriving in San Francisco or departing, leads back to the museum’s collection.

Further, we want to ensure that the museum “follows you” beyond the airport. One could imagine a visitor’s mobile device following them through the airport, and deliberately or passively, collecting objects on display in the terminals or entire exhibitions or facets of the airport itself. That same device could then request and receive related materials from the collection that could be viewed at a departure gate or even offline while sitting on an airplane in flight. That same infrastructure could also be used to deliver materials to passengers in advance of their arrival at SFO, whether it is through the museum’s own online efforts or third-party initiatives like back-of-seat entertainment systems on airplanes.

The lovely thing about a museum like our is that the visitors, and all the places they travel to and from, as well as the airplanes and airlines that are taking them there, are the glue that connects the museum’s different efforts. Place and travel connect them since every thing is from some place and people—the passengers (visitors) passing through the airport—are what connect travel and place.

That is why SFO Museum has focused its initial digital efforts at the macro level, starting with maps of the world (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/blog/2018/07/31/maps/) and the infrastructure to sustain them, moving closer and closer to the micro level, the objects in our collection, working to model the airport’s architecture (from buildings down to individual galleries) (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/blog/2018/08/28/whosonfirst/) as well as the museum’s exhibition history (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/blog/2018/10/17/exhibitions/) along the way.

Who’s On First

Our work extends the Who’s On First (WOF) (https://www.whosonfirst.org/) project, an openly licensed gazetteer with both global and historical coverage, to support indoor locations as well as objects, exhibitions, airlines and aircraft all situated in an explicit geographic context.

WOF describes itself (https://www.whosonfirst.org/what/) as:

- [A]n openly licensed data set. At its most restrictive, data is published under the Linux Foundation’s Community Data License Agreement (CDLA) 1.0 (https://cdla.io).

- Every record in Who’s On First has a stable permanent and unique numeric identifier. There are no semantics encoded in the IDs.

- At rest, each record is stored as a plain-text GeoJSON (https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc7946) file. Our goal is to ensure that Who’s On First embodies the principals of portability, durability and longevity. This led us to adopt plain-vanilla text files as the base unit of delivery.

- Files are stored in a nested hierarchy of directories derived from their IDs.

- There are a common set of properties applied to all records which may be supplemented by an arbitrary number of additional properties specific to that place.

- There are a finite number of place types in Who’s On First and all records share a common set of ancestors. As with properties, any given record may have as complex a hierarchy as the circumstances demand, but there is a shared baseline hierarchy across the entire data set.

- Individual records may have multiple geometries or multiple hierarchies and sometimes both.

- Records may be updated or superseded, cessated, or even deprecated. Once a record is created though it can never be removed or replaced.

- Lastly and most importantly, Who’s On First is meant, by design, to accommodate “all of the places.”

- Who’s On First is not a carefully selected list of important or relevant places. It is not meant to act as the threshold by which places are measured. Who’s On First, instead, is meant to provide the raw material with which a multiplicity of thresholds might be created. From the Who’s On First’s perspective, the point is not that one place is more important or relevant than any other. The point is not that a place may or may not exist anymore or that its legitimacy as a place is disputed. The point is, critically, that people believe them to exist or to have existed.

Fundamentally all museum collections are situated in space and time, if only as a reflection of the need for accurate inventory, tracking between storage and display areas. By extension, all museum collections and collections management systems are inherently spatial-temporal databases.

Location and history, though, are also core to the experience of the objects themselves and in many cases the lenders or lending institutions. Knowing the time and location of an object in the museum could easily be extended to track the time and location of an object both before it is accessioned in to a collection as well as afterwards when it is de-accessioned. As often as not, the place an object is “from” originally is no longer the same place, politically or culturally, by the time it is viewed. All of these dynamics are emphasized in an airport museum where people are traveling to (or arriving from) those same places that the objects on display are from or depict.

Although many collections management systems have some notion of geography, or place, typically location support beyond the warehouse is average to poor. Location information, when it exists, if often scoped to nothing more precise than a country or a locality and limited to point-based geometries. When an organization or consortium has created a gazetteer with more detailed information, those projects have typically been bound to a specific historical period or been geographically regional in focus.

For many years, the gazetteer of record in the cultural heritage sector has been the Getty Institute’s Thesaurus of Geographic Names (TGN) (https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/tgn/), first published in 1997. TGN adopts (and influenced) many of the same principals of the WOF project: Machine-readable documents, stable and permanent identifiers, a hierarchical structure of pointers to related documents and a rich set of metadata properties describing that place. Until 2014, TGN remained a licensed and proprietary data set placing it outside the reach of many institutions and the awareness of those outside the cultural heritage sector. In 2014, TGN was made publicly available as part of Getty’s larger Linked Open Data program (https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/lod/index.html), released under the Open Data Commons Attribution License (ODB-By) (https://opendatacommons.org/licenses/by/index.html).

This was an unqualified good thing and an example for the rest of the cultural heritage sector to follow. Unfortunately, the manner is which the data is published remains problematic. A detailed critique of TGN’s approach (a single 17 gigabyte machine-readable but ultimately human-unfriendly file) is outside the scope of this paper but the consequence of TGN’s decisions is that the data is rendered, if not unusable, then beyond the technical and infrastructure-related means of many who might use it.

SFO Museum has chosen instead to adopt the Who’s On First (WOF) gazetteer for the following reasons:

- The scale and breadth of the project. In 2019, the core administrative data set (https://github.com/whosonfirst-data/whosonfirst-data) for WOF consists of 4.8 million places from continents to neighborhoods, spanning the entire planet. It is actively maintained and updated and has detailed polygons (geometries) for most features.

- Use of the GeoJSON format,now formalized as the Internet Engineering Task Force’s RFC 7946, which is a simple text-based format for describing geometries and properties with broad support in both open-source community and proprietary geographical information systems software, ranging from web-based mapping tools to sophisticated desktop applications to server-side spatial-processing. (Fun fact: Sean Gillies (https://sgillies.net/) one of the original authors of the GeoJSON specification was also the lead engineer on the Pleiades gazetteer of ancient places project (https://pleiades.stoa.org/) .)

- WOF’s dictum that “the data is not the database,” meaning the project aims to be usable with any and all databases, rather than tailored to the specifics of any one tool.

- Concordances are pointers from WOF identifiers to other gazetteers like TGN or Geonames. This ensures greater portability should SFO Museum decide to migrate its services to another gazetteer or geo-infrastructure.

- Use of the Library of Congress’ Extended DateTime Format (EDTF) (https://www.loc.gov/standards/datetime/) a robust syntax for describing uncertain or ambiguous dates (and set to become part of the ISO 8601 date format in late 2019).

- The ability to define multiple, distinct instances of the same place as a kind of historical “linked-list.” Wikipedia defines a linked-list (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linked_list) as a “linear collection of data elements [where] . . . each element points to the next.” It is a data structure consisting of a collection of nodes which together represent a sequence.” For example, the context in which the Olympic Stadium in Sarajevo in 1988 existed was a quantifiably different place than the same geographic location in 1993 or again in 2018. The same could be said of Berlin during the Weimar Republic versus the Berlin of the Cold War or more recently Berlin in the years following German reunification. The list is as long as there are places in the world. In all of these examples, these are the same place geographically but their cultural and political context is dramatically and meaningfully different. WOF assigns each context a unique identifier and then links them together through the use of “supersedes” and “superseded by” pointers.

- The ease with which the WOF data model can be extended to suit the needs of a project like SFO Museum. The SFO Museum digital initiatives demanded that the museum model the history and the evolution of the airport itself, creating stable and permanent geo-referenced records for all the relevant architectural elements, including the airport complex itself, terminals, boarding areas, and galleries. This meant extending the existing hierarchy of administrative place types in WOF to support modeling for indoor spaces.

- Familiarity. This author has been involved with WOF project since its inception (https://whosonfirst.org/blog/2015/08/18/who-s-on-first/), working full-time on the project between 2015-2017 (https://whosonfirst.org/blog/2018/01/02/chapter-two/).

Extending Who’s On First

A central tenet of the WOF project is that the core set of place type descriptors (https://github.com/whosonfirst/whosonfirst-placetypes) be as few and as broad in scope as possible. Each WOF place type is assigned one of three possible roles: Common, Common-Optimal, and Optimal. Common place types are: “Continent,” “Country,” “Region,” “Locality,” and “Neighborhood.”

Place types are used to define the hierarchy (of ancestors) for a place and while any record may have as complex a hierarchy as necessary, one of the few absolute rules in WOF is that every hierarchy contain at least one of the common place types. The rationale for a common set of place types, across the entire data set, is to ensure that two or more independent projects can establish a geographic concordance, with global coverage, requiring only minimal technology and infrastructure costs.

The ability to describe common place types for the entire planet requiring only five database columns is understood to be a reasonable middle-ground given the complexity and nuance of place multiplied by the scale of the planet. By standardizing on the common place types, it ensures that diverse projects can talk about (common) places and do so with the confidence that they are talking about the same thing and, most importantly, the same thing at a specific moment in time.

If a project needs or wants to capture more detail about a place, for example referencing the borough of Brooklyn in New York City, then they will need to add a “sixth” database column. There is no guarantee that another project will also do the same but at least everyone’s efforts can intersect at a common understanding of New York City (locality) and any of its ancestors.

There is not a dedicated place type for airports in WOF. Rather an airport is said to be a (common-optional) “campus” because it is more similar in nature to other campuses than not: A university campus, a medical complex or an office complex. WOF assumes that the specificity of a place can and will be encoded in name-spaced properties unique to that record. For example the abbreviated WOF record for the San Francisco International Airport (SFO) (https://spelunker.whosonfirst.org/id/102527513) is:

"properties": {

"oa:type": "large_airport",

"sfomuseum:placetype": "airport",

"wof:id": 102527513,

"wof:name":" San Francisco International Airport",

"wof:placetype": "campus"

}

At the beginning of 2018, the smallest, most atomic, place type in WOF was the “venue.” Venues are typically, but not exclusively, parented by the “building” place type. Like a “campus” the meaning of the “venue” place type is deliberately fluid and considered to be “any space around which people might gather.” A venue might be a shop or a performing arts center or a public landmark. While SFO Museum’s public art works had previously been classified as “venues” by the WOF project, in 2016, this place type was determined to be insufficient for the overall needs of SFO Museum.

SFO Museum proposed five additional optional place types. Three of them are said to be ancestors of venues while the other two are descendants. They represent common indoor architectural place types that might be applied to other building spaces and whose semantics are meant to flexible enough to accommodate a range of use-cases. They are:

| place type | description |

|---|---|

wing |

A principal subdivision inside of a building. |

concourse |

A secondary subdivision inside of a building (wing). |

arcade |

An arcade is any deliberate or de-facto space inside a concourse. |

enclosure |

An enclosure is any deliberate space inside a venue. |

installation |

Any fixed element (permanent or semi-permanent) that is not an enclosure. |

The machine-readable definition for an “enclosure” consists of a unique numeric ID, a name label, a role and an ordered list of possible ancestors (other place types):

{

"wof:id": 1159268867,

"wof:name": "enclosure",

"wof:role": "optional",

"wof:parent": [ "venue", "arcade", "concourse" ]

}

Although SFO Museum architectural records adopt these generic WOF place types their labels are not suitable for display purposes. SFO Museum supplements these new (WOF) place types with its own “sfmuseum:placetype” property, as follows:

| Who’s On First place type | SFO Museum place type |

|---|---|

wing |

terminal |

concourse |

boardingarea or commonarea |

arcade |

observationdeck |

enclosure |

gallery |

installation |

exhibition |

For example, the abbreviated WOF record for the D-12 Wall Gallery (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/galleries/1159157067/) in Boarding Area D (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/boardingareas/1159396181/), Terminal 2 (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/terminals/1159396121/), is:

"properties": {

"sfomuseum:placetype": "gallery",

"wof:id": 1159157067,

"wof:name": "D-12 Wall Case",

"wof:parent_id": 1159396181,

"wof:hierarchy": [

{

"building_id":1159157271,

"campus_id":102527513,

"concourse_id":1159396181,

"continent_id":102191575,

"country_id":85633793,

"county_id":102087579,

"enclosure_id":1159157067,

"locality_id":85922583,

"neighbourhood_id":-1,

"region_id":85688637,

"wing_id":1159396121

}

],

"wof:placetype": "enclosure"

}

WOF metadata properties are encoded using the GeoJSON format’s “properties” dictionary, which is an arbitrary set of key-value pairs, where each value may be any valid GeoJSON data type (string, integer, dictionary, etc.). WOF properties are enforced through convention, and in some instances, code when processing data using a strictly-typed programming language, rather than a formal schema.

There are ongoing efforts to define a JSON Schema for validation purposes (https://whosonfirst.org/blog/2018/05/25/three-steps-backwards/) but in general, the imperfect nature of geographic metadata and its uneven coverage at a global scale demand the flexibility of an open-ended dictionary. This also allows a project like SFO Museum’s to quickly and easily define its own properties typically through the use custom namespaces (for example, “sfomuseum:” or “flysfo:).

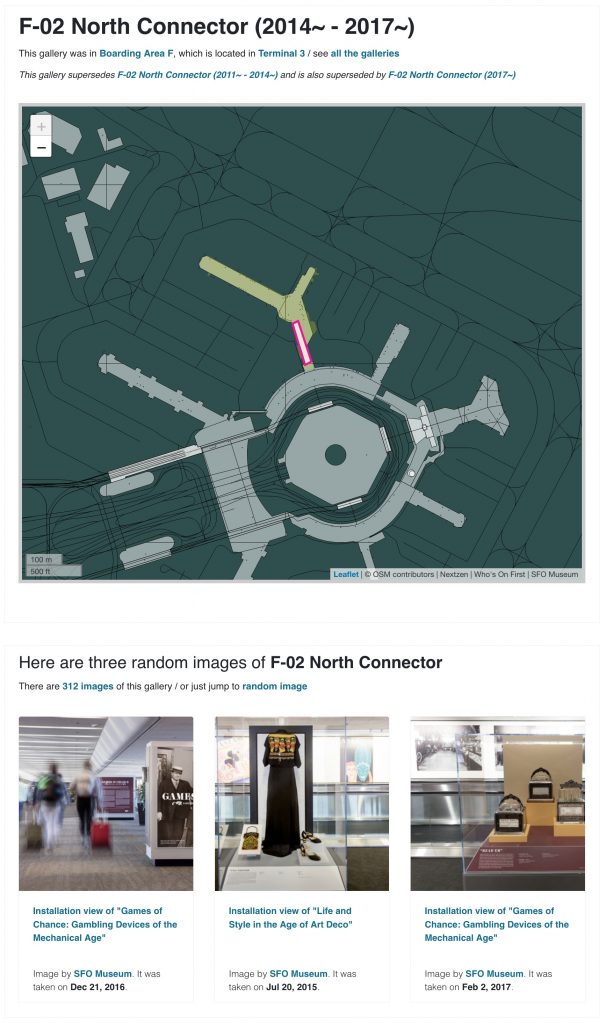

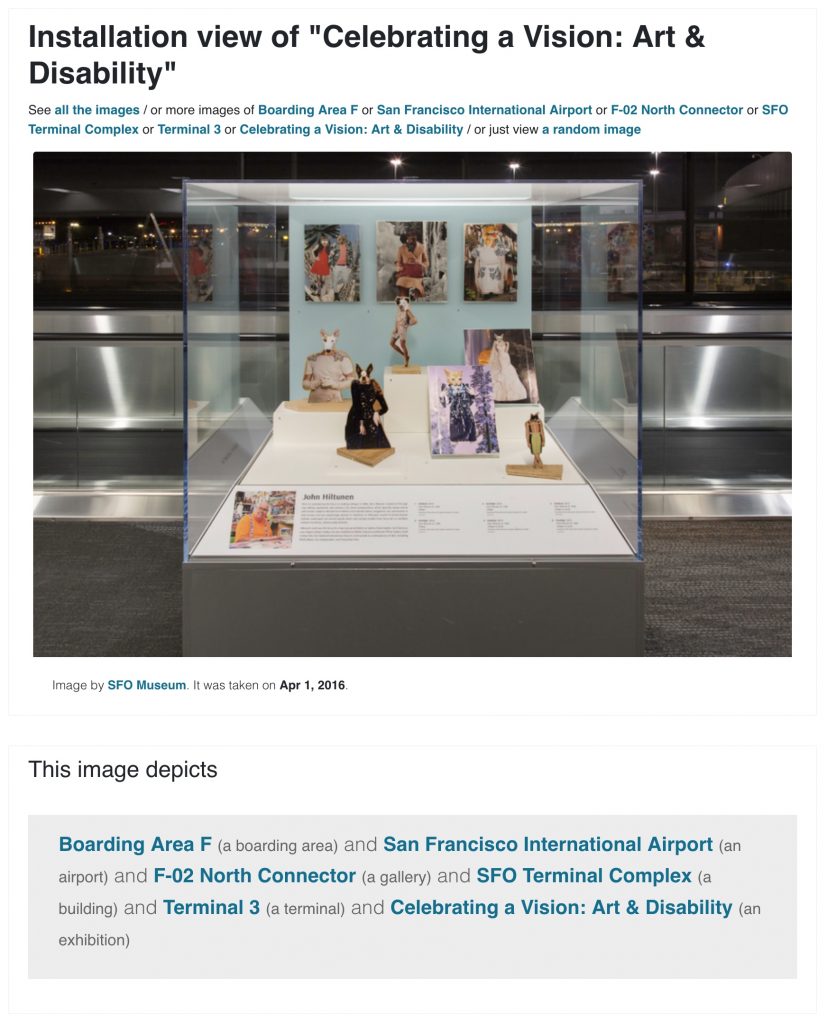

WOF’s flexible approach to modeling data has allowed SFO Museum to associate and contextualize the 1,300+ exhibitions produced during the museum’s 38 year history (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/exhibitions/years/) across 50 gallery spaces (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/galleries/) in addition to the the museum’s aviation collection with the airport as it existed at the time of an exhibition or when an artifact was created.

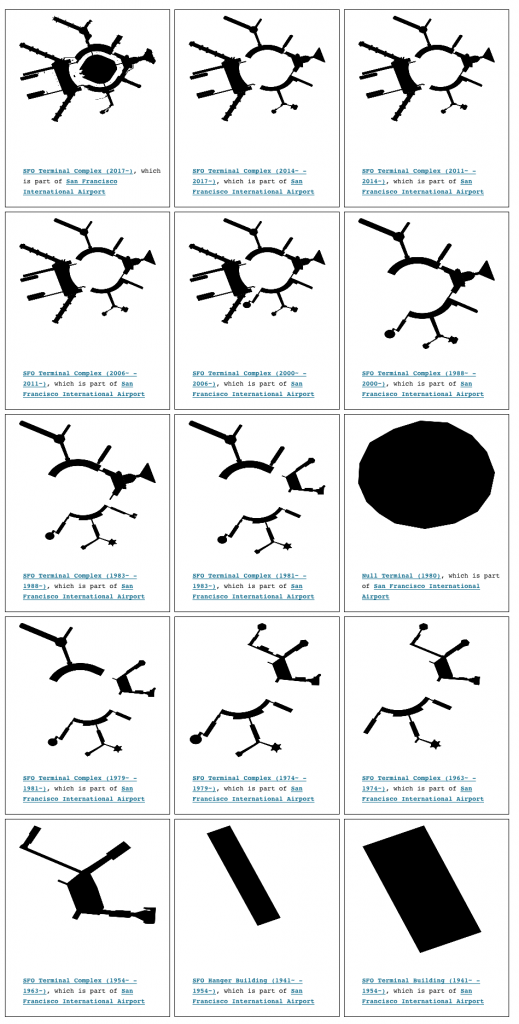

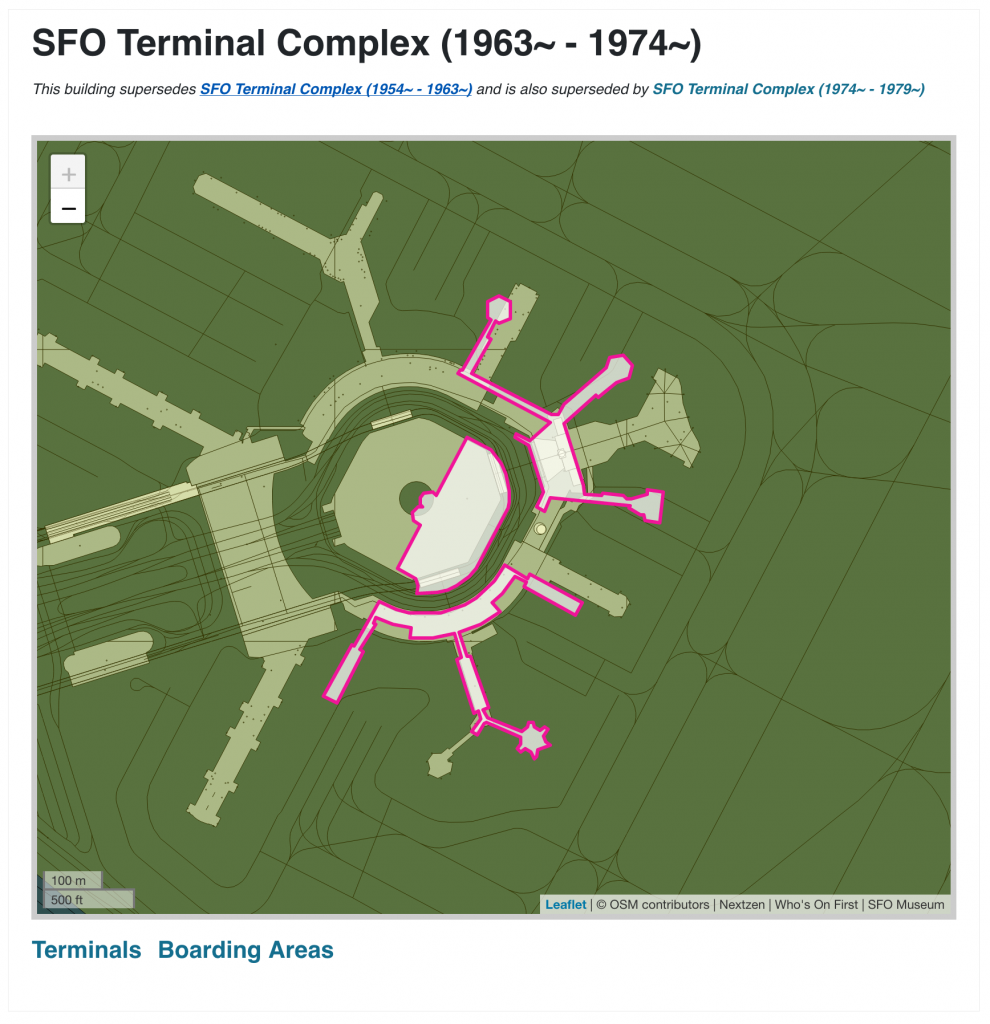

Like the example of the Olympic Stadium in Sarajevo, SFO in 1956 (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/buildings/1159396329/) was a different place than it was in 1980 (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/buildings/1159396327/) than it will be in 2019, when the newly refurbished Terminal 1 reopens as the Harvey B. Milk Terminal (https://www.flysfo.com/media/press-releases/sfo-unveils-designs-terminal-1-harvey-b-milk-terminal). Milk, an activist and civil rights leader and member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, had not even moved to California in 1956 nor had construction on Terminal 1 (first called South Terminal) begun.

In fact, the physical envelope of the airport complex has changed so much so that the pre-security common area in Terminal 2 (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/commonareas/1159157327) is the only architectural element from the airport, circa 1956, that still exists in 2019. It bears repeating: The WOF data model allows us to contextualize objects and events from the aviation collection with the airport as it existed at a specific moment in time. We model a new instance, or record, of the airport terminal complex for each passenger-facing “phase change.”

The terminal complex is said to be the set of buildings that the general public might reasonable expect to “be” the airport. It does not include administrative or other buildings and is distinct from the larger SFO campus. A “phase change” is any significant change or alteration to the airport that a passenger may experience, typically the opening or closing of a terminal or a boarding area. When one of these events occurs, both the old and new record are updated to reference one another, using the WOF “wof:supersedes” and “wof:supersed by” properties.

For example the abbreviated record for Terminal 3 (2011-14) (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/terminals/1159396141/), which superseded Terminal 3 (2006-11) (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/terminals/1159396167/) and was itself superseded by Terminal 3 (2014-17) (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/terminals/1159396157/) is:

"properties" {

"edtf:cessation":"2014~",

"edtf:inception":"2011~",

"wof:id":1159396141,

"wof:name":"Terminal 3",

"wof:superseded_by":[

1159396157

],

"wof:supersedes":[

1159396167

]

}

Note the use of the “edtf:” prefixed properties to encode start and end times for the terminal using the EDTF syntax for approximate dates.

For every new terminal complex, we also create a new record for each of its descendants, from terminals to boarding areas to galleries. This introduces a non-zero amount of overhead, both conceptually and for the tooling used to manipulate these records, that can be unexpected and may seem unwarranted. For example, there were no significant passenger-facing changes in Terminal 3 between the opening of Boarding Area E in 1981 (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/terminals/1159554819/) and its subsequent closure for renovations in 2011 (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/boardingareas/1159396185/) (reopening again in 2014 (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/boardingareas/1159396185/)), yet there are five distinct records for Terminal 3: 1981-83 (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/terminals/1159396129/), 1983-1988 (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/terminals/1159554819/), 1988-2000 (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/terminals/1159554821/), 2000-2006 (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/terminals/1159396123/) and 2006-2011 (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/terminals/1159396167/).

Each of these instances signals a phase-shift in some other part of the larger airport, thus changing the overall context in which T3 itself existed. We feel that this additional complexity is an acceptable trade-off on the grounds that it is easier to stitch things together than it is to pull them apart again, typically with imperfect data.

For example, SFO Museum needs to be able address both of these requests equally:

- Show me everything in the terminal now called “T3.”

- Show me only photos from a particular instantiation of “T3.”

Because historical relationships are modeled as a linked-list of one record superseded by another the first question (“Show me everything in the terminal now called “T3”) is easier to answer, requiring only a small amount of additional computation to traverse that linked-list. The second question (“Show me only photos from a particular instantiation of “T3”” demands strict naming conventions when describing things as well as constantly updated rules and safeguards to account for lapses in data entry.

Having discrete and importantly linked records off of which we can hang context-specific properties, like dates and alternate names, allows us to make “simple things easy and hard things possible,” so the penalty of having to juggle additional records is deemed acceptable.

A Short Detour: Naming Things

A fuller discussion on the nuance and complexities of naming things, in general, and how those names are encoded in WOF documents is out of scope for this document, but precisely because naming things is so important, a short detour is warranted in order to address the repeated use of the “wof:name” property in the examples used in this paper.

The “wof:name” descriptor is one finite set of required properties in WOF, and it is expected to be the 7-bit ASCII transliterated English value of a name. This reflects a desire to have a single default naming scheme for all the places in the WOF data set. Although the decision was made (in 2015) to standardize on English for the “wof:name” property that does not mean the default will only ever be English. At some future date, it may be Chinese or Spanish or another language. The criteria for the “wof:name” property is only that there is a default name and that is the same across all records.

Translations as well as variant, historical, and colloquial names are supported and described through the use “name:”-prefixed properties following the RFC 5646 standard for identifying languages. For example, the abbreviated WOF record for the city of San Francisco (https://spelunker.whosonfirst.org/id/85922583/) looks like this:

"properties": {

"name:eng_x_colloquial":[

"City by the Bay",

"City of the Golden Gate",

"Fog City",

"Fog Cty",

"Frisco",

"Golden City",

"S Fran",

"S. Fran",

"San Fran",

"The City",

"S.F.",

"Bay Area",

"S.F. Bay Area",

"The City by the Bay",

"Baghdad by the Bay",

"The Paris of the West",

"Ess Eff",

"SFC",

"San Francisco City"

],

"name:eng_x_preferred":[

"San Francisco"

],

"name:spa_x_preferred":[

"San Francisco"

],

"name:spa_x_variant":[

"Ciudad de San Francisco"

],

"name:sqi_x_preferred":[

"San Francisco"

],

"name:yue_x_preferred":[

"三藩市"

],

"name:zho_x_preferred":[

"旧金山"

],

"wof:id":85922583,

"wof:name":"San Francisco"

}

This same model has already been applied successfully to represent the many different way airports and airport terminals are labeled (abbreviations, historical names, etc.) and could also be applied to things like credit lines for objects. For further details on the process of evaluating and updating multilingual names in WOF consult the Concordances with Wikipedia data (Olga Kavvada) (https://whosonfirst.org/blog/wikipedia-data/) and Increasing Name Translations in Who’s On First (Nathaniel Douglass and Stephen Epps) (https://whosonfirst.org/blog/2017/08/22/summer-2017-wof/) blog posts on the Who’s On First weblog (https://whosonfirst.org/blog/).

Diverging from (“Breaking”) Who’s On First

This work has caused us to deliberately overload the semantics of the “place type” property, in both the “wof:” and “sfomuseum:” namespaces, which is an approach that will likely need to be revisited in time. As of this writing the list of overloaded terms includes:

| SFO Museum place type | Unofficial Who’s On First place type |

|---|---|

map |

map |

airline |

enterprise |

aircraft |

instrument |

image |

media |

flight |

event |

It is important to note that a) none of these things are actual “places” or even “types” of places and b) none of these unofficial WOF place types are recognized, let alone supported by the WOF project. We are deliberately overloading the meaning of things as a way to continue taking advantage of a tool chain designed for a different purpose.

The benefits of re-purposing and adapting the WOF data format for things that aren’t principally spatial in nature have proven to be greater than the downsides of not adopting a more collection-centric standard or the penalty of confusing otherwise disjoint data models. Place is inseparable from the function of an airport. Airports exist to enable air travel between places (cities, countries, other airports, and so on).

The mandate of SFO Museum’s permanent collection is to tell the story of the airport so the ability to frame that story using an existing and widely deployed gazetteer is immensely valuable. When another service or enterprise that uses WOF talks about a place, we want to be able to quickly and unambiguously find items in our collection related to that place. We also want this approach to extend beyond the objects in the permanent collection to include the place of origin for loan objects as well as the places that objects in temporary exhibitions depict.

We want passengers who are traveling to the San Francisco Bay Area to know, for example, that SFO Museum displayed Preston Gannaway’s photographs of The Farms of West Oakland (https://www.flysfo.com/museum/exhibitions/preston-gannaway-farms-west-oakland) as a function of their destination. We want to enable airlines and third-party developers to be able to associate a person’s journey with the objects in our collection, both permanent and temporary, using the journey itself as the avenue in to the museum. Whether it’s “Radios produced in Pittsburgh . . .” or “Objects from museums in San Diego . . .” or “Stuff you’ve shown from museums in towns serviced by the airport I’m flying to . . .” or “Pictures taken in France . . .,” as a practical matter we need an open, stable, and easy-to-use database of places (a gazetteer like Who’s On First) that a broad range of services beyond the museum can use to make answering these questions possible.

Modeling objects or enterprises or depictions as WOF records is not obvious and demands a leap of faith. It is a relatively small leap when you consider that all of these non-place records can take advantage of everything WOF offers from tooling, to built-in location data, to a robust and flexible set of metadata properties and ways to track relationships and represent ambiguity over time.

This last point is especially interesting to SFO Museum since it provides a way to represent the complex and twisty associations that have existed between airlines and their parent companies (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/blog/2018/12/03/airlines/) since the advent of commercial aviation.

Going forward, we plan to extend this approach to individual objects in the SFO Museum collection as well as the constituent associated with them. WOF’s support for multiple geometries (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/blog/2019/01/14/gates/) associated with a single record may prove especially useful when modeling many different places that any one constituent may have lived or worked in over the course of their life.

Publishing (as) Who’s On First

SFO Museum publishes all of the data described in this paper as open-data under the Community Data License Agreement (CDLA) 1.0 (https://cdla.io/), developed by the Linux Foundation (https://www.linuxfoundation.org/). Data are published as SQLite databases (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org/distributions/sqlite/) on our own website and as Git repositories under the sfomuseum-data GitHub organization (http://github.com/sfomuseum-data).

Data publications are grouped by the class of items they contain:

| repository | notes |

|---|---|

sfomuseum-data-whosonfirst |

WOF records for places related to SFO and SFO Museum (countries, campuses, etc.); these files are cloned from WOF itself |

sfomuseum-data-architecture |

Buildings, terminals, boarding areas and galleries at SFO |

sfomuseum-data-exhibition |

SFO Museum exhibitions |

sfomuseum-data-enterprise |

Airlines and companies related to the SFO Museum collection |

sfomuseum-data-aircraft |

Aircraft related to the SFO Museum collection |

sfomuseum-data-maps |

Aerial maps of SFO airport |

sfomuseum-data-media |

SFO Museum produced media items |

sfomuseum-data-media-flickr |

Selected Creative Commons licensed Flickr photos relevant to the SFO Museum |

sfomuseum-data-flights-* |

Flight data for commercial airlines arriving at or departing from SFO (experimental) |

Data will also be made available through a public web-based application programming interface (API) in early 2019.

Who’s On First Data in Practice

These published data sets are what SFO Museum itself consumes to populate and run its own millsfield.sfomuseum.org (https://millsfield.sfomuseum.org) website. This website operates alongside SFO Museum’s existing online presence and collections website, which is part of the airport’s flysfo.com (https://flysfo.com) website. The Mills Field project and website is described as:

[A] place to consider what it means for a museum in an airport, an airport with over 55 million visitors in 2017, to operate in a world where (almost) everyone is connected to the Internet. It is a place to learn what are the opportunities and what are our responsibilities, as a cultural heritage organization, to everyone who passes through SFO equipped with curiosity and a computer connected to the network?

[It] is not an experiment or a ‘labs’ project. It’s not even our official website. It is a work in progress to understand and to share the arc of our direction as we answer the question above. To determine where we are going, where all these technologies will take us, and to invite you along for the ride.

The Mills Field website is where everything described in this paper is given form and proven, or just as importantly, disproven. SFO Museum’s ambition for digital projects extend beyond a single website, but we use this website as a foundational layer on top of which everything else we do will be built.

As mentioned at the beginning of this paper, SFO Museum has begun its efforts at the macro-level (the whole world) and has been working its way down to the collection itself. The reason for starting with everything that surrounds an object, whether it is a country or an airport or an airline or the gallery space where an object was displayed in, is to ensure a stable and durable infrastructure that allows each and every one of those facets—facets that are common currency in people’s day-to-day lives—to act as a conduit back to those objects and the larger SFO Museum collection.

We also want this infrastructure to be open and available to others, from amateur enthusiasts to third-party developers to other groups at the airport itself. We want them to be able to fashion their own applications from, interpretations of, and uses for the SFO Museum collection. Therefore, it is important to SFO Museum that we are building our own public-facing services on top of the same open data we produce for general consumption. If we hope and expect others to build something interesting from our data then we should be able to prove, if only to ourselves, that we can too.

While it remains early days in the project the decision to explicitly model the SFO Museum collection in space and time has thus far proven fruitful. By promoting place and history as first-class properties associated with every aspect of our collection, and by extension the airport in which it is housed, we are able to offer as many avenues as there are (or have been) places back in to the collection itself.

Cite as:

Cope, Aaron. "Mapping Space, Time, and the Collection at SFO Museum." MW19: MW 2019. Published January 15, 2019. Consulted .

https://mw19.mwconf.org/paper/mapping-space-time-and-the-collection-at-sfo-museum/