Where Are The Edit and Upload Buttons? Dynamic Futures for Museum Collections Online.

Neal Stimler, Balboa Park Online Collaborative, USA, Louise Rawlinson, Cogapp, UK, Andrew Lih, Wikimedia, United States

Abstract

Museum collections offer the potential to be the foundations for a rich participatory ecosystem, in which experts and enthusiasts work together to produce knowledge and understanding. That potential has yet to be exploited. Collections instead continue to be presented as “online card catalogs,” even as the rest of the web has transitioned towards participation as an expected norm. Our online collections are more vibrant than ever (better data, better images, more multimedia), but where are the edit and upload buttons?Keywords: collections online, aggregator, open access, wikimedia, wikipedia, digital collections

Introduction

Museum collections offer the potential to be the foundations for a rich participatory ecosystem, in which experts and enthusiasts work together to produce knowledge and understanding. That potential has yet to be exploited. Collections instead continue to be presented as “online card catalogs,” even as the rest of the web has transitioned towards participation as an expected norm. Our online collections are more vibrant than ever (better data, better images, more multimedia), but where are the edit and upload buttons?

Participation and interactivity (Dupuy, 2015) have become table stakes for web content. Daily interaction with Wikimedia platforms, cloud-based and mobile computing and social media have habituated users to an experience in which they expect to have the ability to create, edit, and publish knowledge in real time. A limited number of efforts in the museum community have begun to explore what reimagining collections with this mindset might look like, but outside of isolated temporary efforts and specific calls to contribute, direct editing of museum collection assets and data remains a nearly unknown phenomenon.

More museums around the world have made their collections open access (Wallace and McCarthy, 2018). These initiatives were driven by: the high cost of administering rights and permissions fees for images of objects not in copyright; the remix culture of the internet; museum staff’s identification of open access as a mission-serving imperative for the 21st century; and community engagement led by academics and, significantly, Wikipedia contributors. The open access movement in its early days focused on opening the “cabinet of curiosity” of collections through application programming interfaces, datasets, images and audiovisual assets. Public response has been positive and engaged through institution-sponsored events, projects and residencies, as well as the community’s interests. These critical efforts have fundamentally shifted collections’ online museum practice for the public from mere access to use and re-use.

What could be undertaken by museums, individually and together, to make online collections part of an interconnected system that participates in the real-time creation, exchange and sharing of knowledge? What are the existing tools presently in place for such change; moreover, how might further “wikification” of museum collections online enhance the user experience as well as the cultural and intellectual vitality of cultural heritage?

This paper provides key examples of collections online, collection aggregators, and offers recommendations as to how museum collections online could become a greater utility in a digital culture primarily through Wikification. The paper places a dynamic collection online experience as a mission-critical imperative for public engagement.

Museum Collections Online: A Remembrance of Resonant Echos

Museum websites emerged in the mid-to-late 1990s, the early iterations of which one can only explore via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine (https://archive.org/web/). These early websites, based mainly on the print models of brochures, provided basic information about physical visitation. This website format was widely considered the primary purpose of museum websites – to introduce and intrigue locals and tourists from farther afield, to come and see what could “only” be experienced onsite. The web of this era served as a “directory” or “table of contents,” and a hint of the world newly connected by hyper-linked information emerging from all corners of the globe. The marketing orientation of these sites, along with constraints on the ability to host, upload and store images – let alone rich media content and complex datasets – contained preview images of highlighted museum objects with short text descriptions summarizing their vast collections. “Collections online,” were initially a mirroring or migration of museum object presentation from glass cases and storerooms in the grid of the gallery onto the grid of the webpage. Museums and the Web, a critically important community and publisher of the history of collections online, chronicles this journey with the most significant and most accessible archive of papers on the topic.

Museum websites then moved into the new millennium. By the 2000s, website components included microsites, experiments in digital publication, Adobe Flash and encyclopedias. Museum ambitions changed from showing representative or significant objects selected by curators to showing the museum’s entire holdings with identifying “tombstone” data along with higher resolution images as computing power, storage and bandwidth improved. Calls for increased access to collections online came from academics, museum professionals and members of the public as social networks were on the rise that promoted individual media making, collections and sharing. The utility of these social platforms and the inclusion of museum collections within them on Flickr (notably Flickr Commons) and Wikimedia platforms, either through a partnership or user-community generated expressions independent of institutions, and signaled to museums that they must address the purpose of collections online and how users wanted to engage on these platforms.

In the 2010s, cloud-based software, such as the Google Suite and Microsoft 365, shifted the real-time expectations for museum technologists who were accustomed to using a patchwork of highly specific and often customized local applications and tools. Increasingly complex integrations between collections management, digital asset management, and web content management systems developed through this period, as the content offering of museum websites expanded with collections online along with other marketing and educational features. Cloud-based productivity applications familiar to museum staff in their personal lives impacted the expectations of their software environment within the institution, and they began to expect industry-specific software to behave like more personalized and popular applications. When possible, these technologies, too, began integrating cloud-based tools into the software ecosystem of their tools for sharing and publishing with the use of services like Amazon Web Services and GitHub repositories to power collections online at scale and increasingly share collection data and images as part of open access initiatives. The rise of mobile applications, smartphones and the mobile web, also drove a significant shift in the design of collections online moving from separate sites for desktop and mobile to dynamic, responsive designs. Museum staff and the public came to prioritize user experience with a greater commitment to user experience testing, design thinking exercises and public online surveys.

As we approach 2020, museum technologists continue to improve and develop collections online. Museums are prioritizing the publication of collection data and images beyond their sites to reach and scale to new potential users. The iterative and idiosyncratic nature of developing museum collections websites has provided diverse pathways for steady innovation, but also contributed to the limited engagement, scalability, and interoperability of collections outside one institution or an aggregator. There are literally thousands of collections online built on different technologies with varying features and functionality. Museums spend significant time, money and staff resources making these decorative and designed presentations of what are essentially data and digital assets. A vital aspect of the future development of collections online will be to treat these platforms as pass-throughs in a network of interconnected and open systems rather than individual locked presentation layers. Museums will need to treat data and digital assets as more tool-like than treasure-like. Either through internal development or partnership, museums are further transforming the relationship with collections online from that of viewing or reading to use and making.

Museum Collections Online Key Examples

In its heyday, the early to mid-2000s, The Powerhouse, with Sebastian Chan (https://www.freshandnew.org/) and colleagues, delivered a collection online program that was admired and still remembered by museum technology professionals around the world. Its open approach to documentation through regular blogging, professional sharing and building tools – like application programming interfaces, including images and adopting Creative Commons legal tools – set the standard then, and continues to have an impact now for museum collections online. Chan discussed changes in these early years of the new millennium in a 2007 Museums and the Web Conference Paper (Chan, 2007). The Powerhouse collection online website can still be accessed and viewed through its evolution on the Internet Archive Wayback Machine from 2006 to 2014 (https://web.archive.org/web/20060702053955/http://www.powerhousemuseum.com/collection/database/). Subsequent collection online projects built by Chan, along with Micah Walter, Aaron Straupe Cope and others at the Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum (Chan, 2015), continued the approach developed at The Powerhouse. The work done at the Cooper Hewitt also inspired many museum technologists. It featured searching by color, collection page citations formatted for Wikipedia, rich collections metadata, application programming interface, GitHub repository, developer tools, public user analytics and more. Collection metadata was also provided with the Creative Commons Zero dedication. Detailed information about the innovations, tools, and resources made between 2011 and 2015 can be found at the Cooper Hewitt Labs blog (https://labs.cooperhewitt.org/) and by exploring the Cooper Hewitt collection online (https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/).

Developing in the parallel with The Powerhouse and Cooper Hewitt was The Brooklyn Museum collection online (https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/collections) in Brooklyn, New York. The Brooklyn Museum team led by Shelley Bernstein (https://www.shell7.nyc/) from early 2000 to the mid-2010s, and subsequently, by Sara Devine (https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/community/blogosphere/author/devinesara/). Deborah Wythe played an important role with rights and permissions. Brooklyn Museum was known for its community engagement and social approach with users on digital platforms. In a version of its collection online, a “Community Posse” existed, where users could select favorites, contribute tags, build personal collections, conservation images, write comments and share public user profiles. One notable example featured a community member who published poetry (Bernstein, 2011) on a number of collection works on the collection online website itself. Some other key features of the online collection were: the adoption of Creative Commons legal tools (Cameron; 2010) exhibition history; formatted captions and object record completion status. Brooklyn Museum was an early and leading participant in Flickr, Flickr Commons and community collection imaging projects, such as Wikimedia Loves Art (Bernstein, 2009). It also identified the critical importance of posting museum collections on both Wikimedia platforms and in Internet Archive (Bernstein, 2010). The Brooklyn Museum team’s approach changed (Bernstein, 2014) in response to user behaviors on third-party social media platforms and mobile applications over time. Their Ask application, too, was notable for the internal wiki (Klinger, 2015) developed to collect research and share knowledge between Brooklyn Museum staff and the public. Ask app questions that were answered by the team may also appear on the collection online when available. The deep history of the Brooklyn Museum’s engagement with communities and collections through digital tools can be found on BKM TECH Blog (https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/community/blogosphere/). Shelley Bernstein took her approach to collections online to The Barnes Foundation, remaking their collection online (Bernstein, 2017) in collaboration with the aforementioned Micah Walter and Aaron Straupe Cope, along with Girlfriends Labs. Explore posts about the collection online project (Barnes Foundation, 2017) and view The Barnes Foundation collection online (https://collection.barnesfoundation.org/).

The Rijksmuseum in 2013 relaunched its collection online and introduced the user platform Rijksstudio (Gorgels, 2013) in tandem with the re-opening of the museum after a period of construction and closure. The Rijksstudio platform showcased beautiful, high-resolution images of artworks with the Creative Commons Zero dedication (Stacey, 2017). Rijksstudio encouraged users (https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/rijksstudio/instructions) to build user collections for personal enjoyment or to share with others. Images could be downloaded, cropped and reused for any number of creative purposes (https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/rijksstudio-inspiration) as demonstrated through marketing campaigns with commercial partners like Etsy (Madewell, 2014), or the individual designers through the Rijksstudio awards (https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/rijksstudio-award) competition. The Rijksmuseum also offered its collection data through an application programming interface (https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/api). Recent updates in 2018 (Gorgels, 2018) brought a refreshed mobile application experience to users along with a ticketing and tour experience. Notable leaders in the Rijksmuseum and Rijkstudio campaigns include Peter Gorgels, Martin Pronk and Lizzy Jongma. Museum Technologists and users alike admire The Rijksmuseum collections online experience because of its fun and easy-to-use design, along with the ability to admire and make of use of thousands of images from one of the world’s great art collections. Rijksstudio makes critical connections and demonstrates the use of collections from online platforms into the physical world.

The Walters Art Museum in 2011 (Kinnett, 2011) remade its collection online. The collection online (https://art.thewalters.org/) features image downloads, user collections, user-contributed tags, exhibition history, and conservation data, provenance data, and web accessibility standards. The Walters Art Museum notably was the first art museum in the United States of America to offer images with the Creative Commons Zero dedication. It also was an early and energetic partner with Wikimedia communities, uploading images to Wikimedia Commons (Roth, 2012), hosting hack-a-thons, and supporting an internship and outreach events. Key leaders in this effort were Gary Vikan, Dylan Kinnett and Sarah Stierch. The Walters Art Museum importantly published its process and projects through blog posts (Stierch, 2015) and a case study (Stierch, 2013). As in other examples, The Walters Art Museum built an application programming interface (https://api.thewalters.org/) with foundational documentation (https://github.com/WaltersArtMuseum/walters-api). It should be considered the most significant open access museum collection website of its era in the United States from which others have been modeled. Then Director of The Walters Art Museum, Gary Vikan (Art Daily, 2015) stated: “By adding conservation histories and exhibition records to our works of art site, the Walters is demonstrating its belief that openness and transparency are key components to holding artworks in the public trust.” And, furthermore Vikan offered, “As an additional element to eliminating admissions fees at the Walters, the works of art site does away with barriers of access to the museum’s collection and allows a depth and quality of information on artworks that will appeal not only to scholars but also to art enthusiasts, students, and the casual online visitor.”

The Rhizome ArtBase (https://rhizome.org/art/artbase/), launched in 1999, plays an important and unique role in the history of collections online. It was a free and open digital art repository that anyone could upload and contribute to until 2008. Creators could opt to add a Creative Common License (Cameron, 2007) to the work upon upload, meaning that contemporary art could be assigned open licenses at the time of donation to an institutional repository. Artworks are now added to ArtBase by curatorial invitation and through Rhizome’s commissioning and exhibition programs. The ArtBase is crucial because it demonstrates considerations not only about the preservation of born-digital artworks but the constantly changing nature of the access, display, interaction, and preservation of collections online. An iterative history of the Artbase can be read on the Rhizome editorial blog (https://rhizome.org/editorial/tags/artbase/). Ben Fino-Radin’s report, Digital Preservation Practices and The Rhizome Artbase, (Fino-Radin, 2011) is another significant publication. Notable figures include Mark Tribe, Rachel Greene, Ben Fino-Radin, Lauren Cornell, Michael Connor, Dragan Espenschied, and Zachary Kaplan.

These examples of innovative collections online identify critical historical trends and an iterative while forward-looking approach to museum collections online. These key institutions made strides in moving from a merely presentational form of collections online into user participation and interaction within and external to collections online platforms. Looking back to these specific institutions over the last two decades demonstrates that a prosocial orientation to serve users, not only self-identified institutional priorities, directly manifested in the new experiences of museum collections that point toward a future which is even more collaborative. These collections enabled actions with museum collections that have extended their impact, reach and value for the public.

Museum Collection Online Aggregators

In partnership with the academy, GLAM institutions (Galleries, Libraries, and Archives and Museums), government or commercial entities, museums have contributed images, data, and links to collection online aggregator portals. These websites act as meta-collections hosting data and images from other contributing institutions. They were created to bring collections from a range of institutions into greater visibility for users through enhanced discovery and search. Aggregators aimed to attract the attention of user communities so that more could be achieved than by an individual institution. Aggregators have been a cause and effect of the scaling-up of digital collections online as agreements, time-conditioned funding and digitization campaigns drove individual institutions to deposit more and more content into these shared platforms. Collaborative platforms also led institutions to establish partnership roles and programs that could spearhead collaboration and sustain these platforms over time. Platform launches became key press moments for digital engagement with the recognition that more museum users access and experience collections in interaction with digital platforms than they could by visiting an individual institution or exhibition.

Aggregator platforms provided users opportunities to access multiple objects simultaneously and discover possible shared associations. A user could compare data and media assets from each contributing institution and make connections between points of similarity or difference based on the content they encountered. Prior to museums publishing their collections with application program interfaces, GitHub repositories and downloadable images with Open Access, aggregators were among the few options to reach audiences externally to an institution’s platform in addition to social media. Much of this work was done by hand before automated processes with highly manual and batch processes. Refresh and currency of assets and data have been and still are a challenge with aggregators. To keep content dynamic and engaging, aggregators built digital publication tools, often more advanced than the contributing institutions’ own toolsets, to create interactive features that had rich multimedia, zooming and video. Working with aggregators too challenged museum institutions to improve their infrastructure and workflows in order to participate in these initiatives. Aggregators pulled individual institutions and the museum technology sector forward.

Among the challenges with aggregators is managing partnerships. Partners can come [and often go] because of changes in funding, staff and technology. A contributing institution may struggle to maintain their relationship with an aggregator because staff time and money focusing on the partnership could be viewed as taking resources away from the institution’s own goals or platforms. That is why an organization needs to ensure its mission is aligned with the aggregator’s and that the importance of participating is a shared priority for both organizations. Shared responsibility for policy, service and financial obligations are critical, too. Museums participate in aggregators for a number of reasons – from a peer’s participation; alignment with engagement strategy; or the opportunity to utilize new technologies.

Museum aggregators were developed in parallel with Wikimedia platforms in the early and mid-2000s when institutions were skeptical of Wikimedia and communities of practice, such as OpenGLAM and GLAMWiki, that were in the process of formation. These peer institutional networks influenced ideas about openness sharing and collaboration. Aggregator partners benefited not only from contributors data and digital assets but by having opportunities to create new content and products for users. The real impact and benefit of aggregators for individual institutions are often not widely known to the public because metrics are often part of private agreements with respect to data sharing. Some platforms do show views or report minimal levels of interaction, but museums and aggregators will continue to need to evaluate the resonance and relevance of these partnerships continually. Greater transparency around user analytics through public dashboards and reports would undoubtedly enhance this collective understanding. The value and impact of aggregators have been a long-term question for the museum sector, as documented in a 2004 Museums and the Web paper by Willy Lee (Lee, 2004).

Aggregator Examples

Artstor (http://www.artstor.org/) was a critical part of the history of digitization from analog slides to digital data and images. It was created with support from the Andrew Mellon Foundation to enhance access to and augment the teaching of the arts and humanities. University visual resource collections digitized and uploaded their slides with other global institutional partners contributing their images to the platform over time. Artstor absorbed the Art Museum Image Consortium (AMICO) in 2005 (Arstor, 2004), an important development for the digitization of visual resource materials closely linked with Museums and the Web (Bearman and Trant, 1998). In an initiative led by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, called Images for Academic Publishing (IAP), launched in 2007, museums joined together to provide high-resolution images that could be used without additional permissions or fees for scholarly publishing by meeting specific criteria. The IAP program was a milestone for art museums that contributed to open access by providing essential and demonstrable support for scholarship as it evolved with digital technology (https://support.artstor.org/?article=images-for-academic-publishing). Now part of Ithaka, Artstor continues to provide over 2.5 million assets with data and images provided by institutional partners. It is also a leader in the provision of open access images with its Public Collections (http://www.artstor.org/public-collections) portal, where anyone may download images that are without copyright restrictions, built on its JSTOR Forum (http://www.artstor.org/jstorforum), formerly “Shared Shelf Commons” tool.

Founded in 2008 by Carter Cleveland, Artsy (https://www.artsy.net/) was a new type of aggregator for the art world. Initially aimed at the contemporary art market, auction houses and galleries, Artsy expanded into museum partnerships (https://www.artsy.net/institution-partnerships). The collection platform (https://www.artsy.net/collect) offers a blended presentation of artworks for sale in auctions houses and galleries alongside artworks in permanent museum collections. Artsy brings the market and museums into direct contact on the platform which is valuable not only for current collectors but those studying the history of collecting. Artsy’s Art Genome project (https://www.artsy.net/about/the-art-genome-project) is notable for its contributions to art historical metadata. Artsy is also an educational platform (https://www.artsy.net/about/education) as it features over 5,000 artist biographies, exhibition histories and a selection of downloadable images. On the development side, Artsy’s engineering team has an open source repository (https://artsy.github.io/open-source/).

Created in 2008, Europeana (https://www.europeana.eu/), was formed as part of the evolution of the European Union to create a shared European culture and identity from member states pancultural heritage (Pekel, 2013). It was an earlier adopter of Creative Commons legal tools including the provision of metadata with Creative Common Zero dedication in 2011 (Peters, 2011). Drawing upon not only substantive art collections (https://www.europeana.eu/portal/en) contributed by partners, it also contains images and data related to a variety of other subject areas such as archaeology, fashion, manuscripts, music and natural history. Europeana is particularly notable, in the category of government or “national” aggregators, because of its drive to activate interaction with collections drawn upon from partner institutions through feature galleries and online exhibitions and campaigns. Its work with data publication, impact studies, tool standardization, and advocacy efforts are also significant contributions to the museum field. Europeana is an internationally engaged and multilingual organization, which works across borders to bring cultural heritage content to the world. The professionals, like Douglas McCarthy, and community involved in Europeana are part of what make it so resonant and impactful. Other notable government or national aggregators for the museum sector include ArtUK (https://artuk.org/), Biodiversity Heritage Library (https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/), Digital Public Library of America (https://dp.la/), Trove National Library of Australia (https://trove.nla.gov.au/) and Digital New Zealand Ā-tihi O Aotearoa (https://digitalnz.org/).

Also launched in 2008 was Flickr Commons (https://www.flickr.com/commons), a portal built on top of a social sharing platform for images with cultural heritage collections. Institutional partners (https://www.flickr.com/commons/institutions/) added image collections and nurtured communities around these collections through user groups and challenges. A cited accomplishment of Flickr Commons (Bray, et al, 2011) was the rights statement “no known copyright restrictions” (https://www.flickr.com/commons/usage) along with the evidence that participant engagement on Flickr Commons was higher than on the institution’s websites scaling cultural heritage. Flickr Commons featured nuanced contributions of metadata, tags, user comments, user collections and user communities (https://www.flickr.com/groups/flickrcommons/). Flickr Commons’ images could be embedded into social media and other web platforms with persistent URLs and were early adopters of Creative Commons legal tools (Shaden, 2004). The company has been sold multiple times, but the platform has been thus far maintained throughout these challenging times of transition in search of stability. Flickr Commons raised concerns for the museum community, as it foregrounded the challenges that arise when private companies build more user-friendly platforms and tools than museums themselves provided. Flickr Commons, in comparison to its cultural heritage partners, however, lacked the framework for the tradition of stewardship essential to serving museums’ missions. Flickr Commons shed light on the reality that images that are free and easy-to-use have more dynamic veracity than those that are restricted. A recent concern in 2019 (Merkley, 2019) was Flickr’s acquisition by SmugMug, which placed the Commons in jeopardy to be rescued through advocacy from users and notably Creative Commons. Flickr Commons, now more than eleven years old (Roncero, 2019), continues to serve as an example for aggregators over the last decade. It also paved the way for the development of the global Open Access movement.

Launched in 2011 (Sood, 2011) as The Google Art Project, then known as Google Cultural Institute and now Google Arts and Culture (https://artsandculture.google.com/), this aggregator platform has received attention from the public and museum professionals. The only major technology company to date to build a cultural heritage platform at global scale (e.g., Apple or Microsoft), Google Arts and Culture (https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/about/) introduced an enhanced collections online features by extending and creating new relationships with collections using gigapixel images, high resolution zoom, linked interior street views and maps, mobile applications, smartwatch wallpapers, augmented and virtual reality, 360 degree video, machine learning, artificial intelligence and online exhibition features. Google achieved a scale and impact of awareness that few other aggregators have thus far, bringing partners (https://artsandculture.google.com/partner) to collaborate in ways they otherwise would not powered by its brand identity, publicity, and tools. Google’s lab (https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/thelab/) in Paris has been a site for experimenting with innovative approaches at the intersection of art and technology. Google Hangouts OnAir (Now YouTube Live) and education platform (Google for Education, 2019) brought museum collections to classrooms around the world, becoming an accessible and comprehensive learning resource. Collections from museum partners worldwide have come together on this platform in ways not otherwise possible because of centralized cloud-based collections management tools. The centralized platform and suite of tools make Google Arts and Culture an influential aggregator, but it too is limited by its essentially “presentational character.” There are degrees of interactivity, but these do not transcend playing and viewing into making. Concern has come around: rights and permissions (Dewey, 2015); a private company’s interests in cultural heritage (Chen, 2018); the future sustainability of the platform beyond search (Davis, 2016); and the lack of publicly published metrics that demonstrate user and institutional benefits from the collaborations.

Founded in 1996, The Internet Archive (https://archive.org/) has as its mission to “provide universal access to knowledge.” The team at the archive, and charismatic co-founder Brewster Kahle (http://brewster.kahle.org/), have significantly contributed to preservation of the culture of the Internet through its well-known Wayback Machine (https://archive.org/web/) which archives web pages mentioned elsewhere, but also through providing access to and preservation of software, datasets and other digital assets, such as images, moving images and texts. It is a meta-collection of the past and present of that which is born digital and has been digitized. The Internet Archive is critically important because of its open and catholic approach to collecting (Recode, 2017) through machines, communities and partnerships. It is not curatorial in the traditional museum sense, in that rather than making a limited selection of assets, it seeks to collect as much knowledge as possible for the present and future purposes of users. It understands that what society values today will change and even more so over time. At the Internet Archive, media types and sources are presented on one holistic platform that includes massive search results that show interconnections. Individual object pages provide detailed metadata along with features of favoriting, reviewing, view statistics and download options, often in multiple formats. With its commitment to open access and the public domain (Bailey, 2018), The Internet Archive ensures one of its primary roles is to enable and encourage the use of its collections. Through the public publishing of its user statistics (https://archive.org/stats/), The Internet Archive, has nearly four million visits daily, meaning that its engagement overwhelms the physical attendance at the world’s top ten most visited museums every year (Sharpe and Da Silva, 2010). A history (Rackley, 2010) of The Internet Archive from 1996 to 2007 provides a useful framework for understanding its foundational development.

Wikimedia and the Wikification of Museums Collections Online

Launched in 2001, by co-founders Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger, Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Wikipedia) was created as a freely accessible online encyclopedia without central authority control for contributing and editing content. Other platforms and tools developed to support the growth of content in the online encyclopedia include databases Wikidata (https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Wikidata:Main_Page), digital asset management tools Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Main_Page) and a suite of others. Content on Wikipedia and its related platforms use open access or “copyleft” copyright policies (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Copyrights) for its platforms, meaning that content in many cases can be used, modified and reused freely with permission in alignment with assigned licenses and legal deeds. Wikimedia and its platforms use Creative Commons legal tools in many cases that are not restricted by the terms of non-commercial uses. Wikipedia is one of the world most popular websites (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_most_popular_websites).

The GLAM-Wiki (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:GLAM) worldwide communities have been active and leading contributors to the growth of Wikimedia platforms through the contributions of data, media assets and more programmatic efforts such as Edit-a-thons, article creation campaigns, residencies or the development of tools. Contributors are both independent volunteers and GLAM sector professionals, who are equally committed to the sharing of free knowledge through collections and research. The first Wikimedian-in-Residence was Liam Wyatt (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:Wittylama) at The British Museum in 2010 (Cohen, 2010) with a five-week residency creating articles in dialogue with museum staff. The GLAM-Wiki US Consortium (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:GLAM/US/Consortium) played an important role in engaging initiatives in The United States between GLAM institutions and volunteers. Another contribution in moving forward the relationship between museums and Wikimedians was Lori Byrd-McDevitt (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:LoriLee) and her notion of “Open Authority,” (Salas, 2013) which asked institutional expertise to welcome contributions from the public in an effort to establish an information production process that collaboratively validates knowledge through dialogical and “wiki-like” methods and tools. Wikimedia chapters in New York City (https://nyc.wikimedia.org/wiki/Home) and Washington, D.C. (https://wikimediadc.org/wiki/Home) were important centers of activity for the development of ongoing relationships between GLAM institutions and community members in the United States. The effort and impact of GLAM-Wiki communities were impactful increasing the number of participating institutions and collaborative projects at a multiplying number of institutions across the globe.

These efforts, and those of the aforementioned institutional collections online and aggregators, contributed to the conception of Wikification (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikification) or as defined by Richard Knipel (Knipel, 2017) working as the Wikimedian-in-Residence at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “The goal I set for myself was to ‘Wiki-fy The Met, and Met-ify the Wiki’—to bring Wikipedia’s collaborative spirit to the Museum, while also bringing The Met’s scholarly expertise to Wikipedia.” Neal Stimler offered a furthering definition (Stimler, 2019) with a greater future orientation in the museum context, “museum collections publishing to Wikidata and Wikimedia Commons through automated processes and museum collections online becoming more like Wikipedia with multiple and real-time editors, including those external to an institution.” Museums have significantly struggled with standardized metadata schema, authority control of research and published information, data validation, and data silos (Lih, 2019). Museums often act on their own or in consortia, but these independent efforts and projects in partnership while important iterative steps towards improvement, lack the impact and scale that further automation, integration, and synchronization could be achieved with Wikification.

The Tate (https://www.tate.org.uk/search?type=artist) uses artist biographies sourced from Wikipedia for its collection online. This practice makes sense in many contexts for basic introductory information that is built on a shared platform of authorship and publication with secondary sources cited. Museums that have invested time in creating artist biographical data for their websites, not to mention historical printed publications or their paywalled digital versions, now are a direct example of siloed and incomplete data that is inefficient in its compiling and updating by individual parties. Matthew Lincoln (Lincoln, 2018) has written about the value of using Wikipedia for information that can be shared across institutions and has advocated for museums changing their data and publication practices towards unique contributions for content related to the specific needs of their collections. Lincoln points out that distributing authority is logical and reminds institutions to design content for users rather than for self-appointed ends.

What might Wikification look like on a museum’s own collection online or an aggregator platform? It would include real-time and open editing of collection and research data on the collection online platform, with authority verification to distinguish institutional contributors such as curators, conservators and researchers from those outside the institution whether they be researchers, passionate amateurs or casual users alike. This sorted and identifiable editing with discussion pages and view history, like a Wikipedia page, would create opportunities for dynamic contributions and editing of knowledge, and distinguish institutional expert and professional knowledge while acknowledging the contributions of others preserving the accuracy of information. The data contributed by the institution and by external contributors would be openly licensed with Creative Commons tools to ensure parity for access and use for multiple user communities. Bots and humans would monitor the potential editing of information that violates terms and conditions. Wikification would also include multilingual translation and the ability for users to upload media assets and associated metadata to the collection with open licenses building the collective corpus of information about an individual object from multiple sources and creators, including the future of XR assets, audio, and more. Individual and aggregator portals would serve as open repositories as much as for the automatic and on-demand use data and digital assets. Individual and bulk use would be tracked on the repository side, along with collection records, which would be shown as visible statistics on public dashboards to demonstrate engagement.

A main priority and function of the content contributed on any collection online, or aggregator platform, would be its automatic synchronization with Wikimedia platforms, such as Wikimedia Commons and Wikidata (Simonite, 2019), as a third party and decentralized platform. This development in parallel on Wikimedia platforms places the benefit of museum collections into the hands of the highest number of potential users and affords opportunities for standardization for structured data across cultural heritage resources. Publishing data on shared platforms and tools helps museums to act as connectors of things outside the walls of their institution or consortia initiatives. Furthermore developing tools on top of Wikimedia platforms supports “knowledge as service” and “knowledge equity” around the world (https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Strategy/Wikimedia_movement/2017), as those institutions that have resources to share can help build the infrastructure needed by colleagues and peers globally as their collections and culture come online with digitization and access anew. In this way, Wikimedia platforms, powered by collections from institutions the world over act as interactive and connected Rosetta Stone for the future of cultural heritage.

Conclusion

Expectations of collections online are heightening within the sector, and increasingly amongst users. Functionality which may, until recently, have been categorized as ambitious and progressive now has a principal place on the web. The examples in the field, as described in this paper, prove the feasibility of many of features we should expect across the board from collections online: application programming interfaces; open-access approach to media and content licensing; integration with source material (and didactic and interpretive content) from other institutions; and open-source approach to development. As a field, we should be promoting these as industry-standard. Perceived barriers to achieving these baseline developments are the often mentioned budgetary, resource and cultural limitations of any organization. However, it is vital that these hearsay remarks are challenged and advanced upon to move forward within an institution for the benefit of users.

The “futurecast” functionalities for collections online are features we are, at present, only seeing on the horizon that are primarily influenced by Wikimedia platforms and ideas focusing on Wikification. These include: collaborative real-time editing of information on collection objects within their native collection; linked open data; open source repositories, publicly visible engagement metrics for collections online, collaborative cross-referencing between institutional online collections; automated data syncing between institutional or aggregator sites and Wikimedia platforms; 3D models; XR online experiences in collections; and useful implementation of AI in the form of chatbots for online user engagement with collections. Beyond this, naturally, there is nearly an infinite list of possibilities for the future of collections online. With time, the vision of a museum commons through dynamic collections online is coming further into view (Edson and Cherry, 2009).

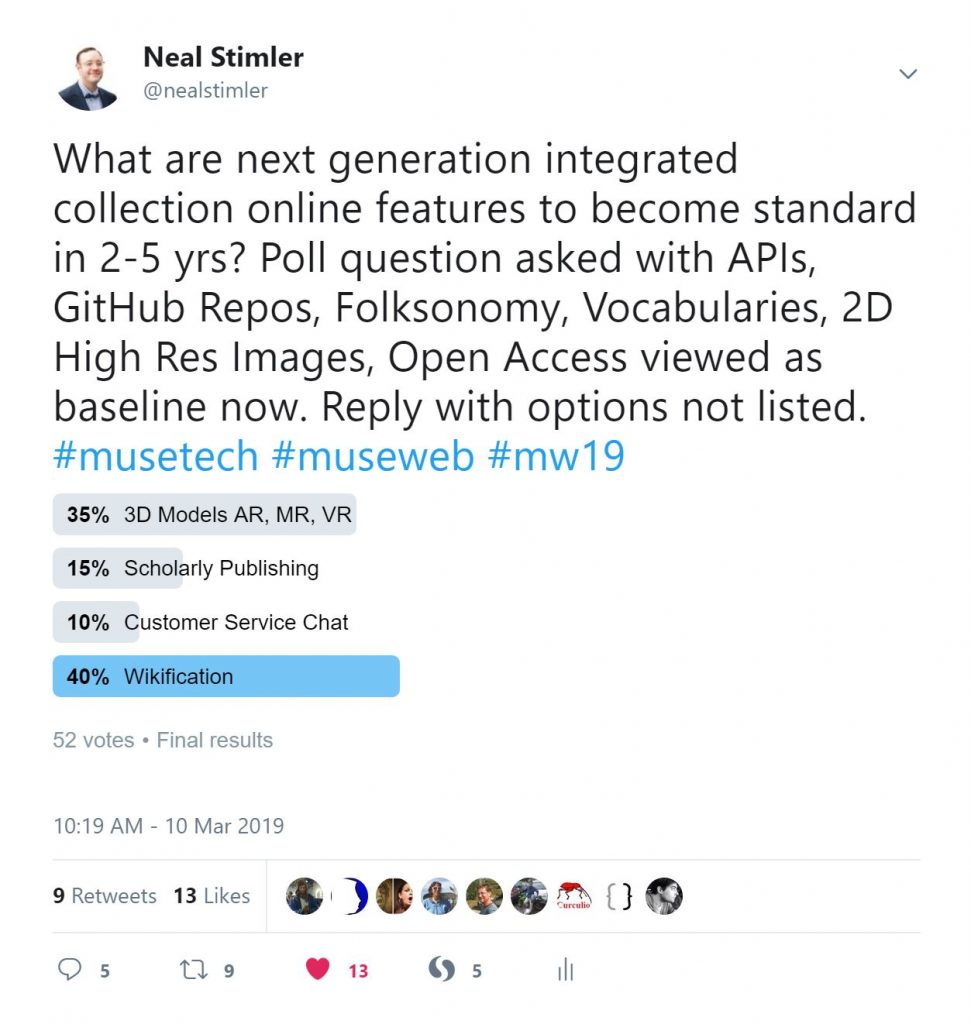

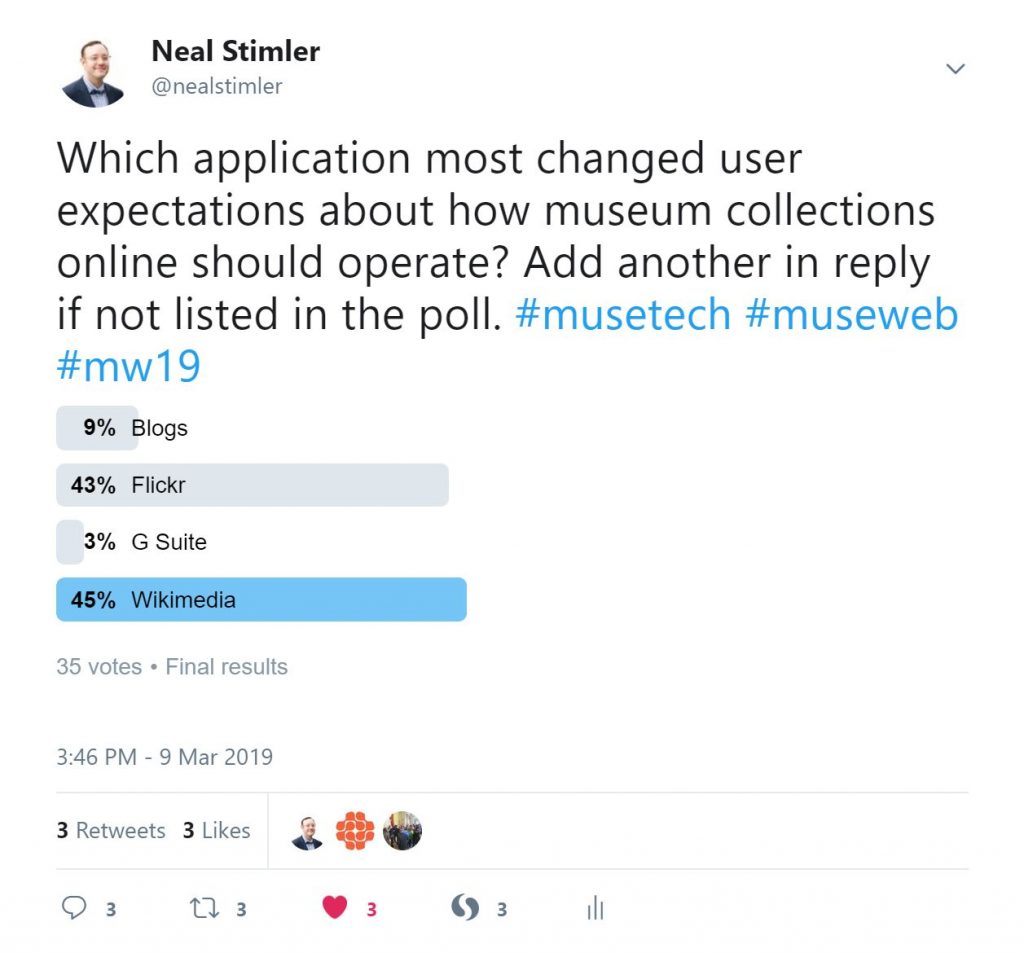

Twitter Polls

As part of the creation of this paper, Neal Stimler ran a series of Twitter polls seeking feedback from Museums and the Web communities about their views on collections online. These informal polls contributed to the ideas presented in this paper. Thanks to all those who contributed and participated.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to our paper collaborators, led by principal author Neal Stimler, with contributions from Mike Dickison, Andrew Lih, Louise Rawlinson and Koven Smith. Thanks as well to all those who have contributed to the development of collections online in the past, present and future.

References

“Walters Art Museum removes copyright restrictions on 10,000 images.” Art Daily. Published 2015. Consulted April 2, 2019. http://artdaily.com/news/50884/Walters-Art-Museum-removes-copyright-restrictions-on-10-000-images

Artstor. “ARTstor and AMICO Combine Efforts to Distribute Digital Images for Museums and Higher Education.” Artstor Blog. Published June 1, 2004. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://artstor.blog/2004/06/01/artstor-and-amico-combine-efforts-to-distribute-digital-images-for-museums-and-higher-education/

Bailey, Lila. “Join us for A Grand Re-Opening of the Public Domain.” Internet Archive Blogs. Published December 4, 2018. Consulted April 3, 2019. https://blog.archive.org/2018/12/05/join-us-for-a-grand-re-opening-of-the-public-domain-january-25-2019/

Bearman, David and Jennifer Trant. “Economic, Social, and Technical Models for Digital Libraries of Primary Resources: the example of the Art Museum Image Consortium (AMICO).” New Review of Information Networking. #4. 1998. pp. 71-91. Consulted April 2, 2019 http://www.archimuse.com/papers/amico/index.html

Bernstein, Shelley. “Wikipedia Loves Art, full house!” Brooklyn Museum. BKM TECH. Published January 1, 2009. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/community/blogosphere/2009/01/26/wikipedia-loves-art-full-house/

Bernstein, Shelley. “Cross-posting the Collection to Wikimedia Commons and the Internet Archive.” Brooklyn Museum. BKM TECH. Published April 12, 2010. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/community/blogosphere/2010/04/12/cross-posting-the-collection-to-wikimedia-commons-and-the-internet-archive/

Bernstein, Shelley. “Poetry Comes to our Collection Online.” Brooklyn Museum. BKM TECH. Published April 12, 2011. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/community/blogosphere/2011/04/12/poetry-comes-to-our-collection-online/

Bernstein, Shelley. “Social Change.” Brooklyn Museum. BKM TECH. Published April 4, 2014. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/community/blogosphere/2014/04/04/social-change/

Bernstein, Shelley. “Rethinking the museum collection online.” The Barnes Foundation on Medium. Published April 11, 2017. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://medium.com/barnes-foundation/rethinking-the-museum-collection-online-e3b864d8bb39

Bray, P. et al. “Rethinking Evaluation Metrics in Light of Flickr Commons.” J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds). In Museums and the Web 2011 Proceedings. Archives & Museum Informatics. Published March 31, 2011. Consulted April 3, 2019. http://conference.archimuse.com/mw2011/papers/rethinking_evaluation_metrics

Cameron. “Brooklyn Museum.” Creative Commons Blog. Published February 5, 2010. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://creativecommons.org/2010/02/05/the-brooklyn-museum/

Cameron. “Rhizome integrates Creative Commons licenses into ArtBase.” Creative Commons Blog. Published July 27, 2007. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://creativecommons.org/2007/07/27/rhizome-integrates-creative-commons-licenses-into-artbase/

Chan, Sebastian. “Tagging and Searching – Serendipity and museum collection databases.” J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). In Museums and the Web 2007 Proceedings. Published March 1, 2007. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://www.museumsandtheweb.com/mw2007/papers/chan/chan.html

Chan, Sebastian and Aaron Cope. “Strategies against architecture: interactive media and transformative technology at Cooper Hewitt.” N. Proctor & R. Cherry (eds). In Museums and the Web 2015 Proceedings. Published April 6, 2015. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://mw2015.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/strategies-against-architecture-interactive-media-and-transformative-technology-at-cooper-hewitt/

Chan, Sebastian. Fresh & New(er): discussion of issues around digital media and museums. Last Updated March 31, 2019. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://www.freshandnew.org/.

Chen, Adrian. “The Google Arts and Culture App and The Rise of The ‘Coded Gaze’.” The New Yorker. Published January 26, 2018. Consulted April 3, 2019 https://www.newyorker.com/tech/annals-of-technology/the-google-arts-and-culture-app-and-the-rise-of-the-coded-gaze-doppelganger

Cohen, Noam. “Venerable British Museum Enlists in the Wikipedia Revolution.” The New York Times. Published June 4, 2010. Consulted April 3, 2019 https://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/05/arts/design/05wiki.html

Davis, Ben. “Google’s Sprawling New Art App Has Grand Ambitions But Is Still Pretty Clunky.” Artnet News. Published 20, 2016. Consulted April 3, 2019. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/google-arts-culture-app-grand-ambitions-566183

Dewey, Caitlin. “Google’s quest to make art available to everyone was foiled by copyright concerns.” The Washington Post. Published March 4, 2015. Consulted April 3, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-intersect/wp/2015/03/04/googles-quest-to-make-art-available-to-everyone-was-foiled-by-copyright-concerns/

Devine, Sara. “Author Sara Devine.” Brooklyn Museum. BKM TECH. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/community/blogosphere/author/devinesara/

Dupuy, Alain, Brigitte Juanals, and Jean-Luc Minel. “Towards open museums: The interconnection of digital and physical spaces in open environments.” N. Proctor & R. Cherry (eds). In Museums and the Web 2015 Proceedings. Published January 13, 2015. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://mw2015.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/towards-open-museums-the-interconnection-of-digital-and-physical-spaces-in-open-environments/

Edson, Michael and Rich Cherry. “Museum Commons. Tragedy or Enlightened Self-Interest?” In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds). In Museums and the Web 2010 Proceedings. Archives & Museum Informatics. Published March 31, 2010. Consulted April 3, 2019. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2010/papers/edson-cherry/edson-cherry.html

Fino-Radin, Ben. “Keeping it Online.” Rhizome Blog. Published August 5, 2011. Consulted April 2, 2019 http://rhizome.org/editorial/2011/aug/5/keeping-it-online/

Google for Education. “EDU in 90: Google Arts & Culture.” YouTube. Published August 22, 2018. Consulted April 3, 2019. https://youtu.be/r3bLtn8DLYo

Gorgels, Peter. “Rijksstudio: Make Your Own Masterpiece!” N. Proctor & R. Cherry (eds). In Museums and the Web 2013 Proceedings. Published January 28, 2013. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://mw2013.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/rijksstudio-make-your-own-masterpiece/

Gorgels, Peter. “Rijksmuseum Mobile First: Rijksstudio Redesign And The New Rijksmuseum App.” N. Proctor & R. Cherry (eds). In Museums and the Web 2018 Proceedings. Published January 14, 2018. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://mw18.mwconf.org/paper/rijksmuseum-mobile-first-redesign-rijksstudio-the-new-rijksmuseum-app/

Kinnett, Dylan. “The Online Collection of the Walters Art Museum.” Museums and the Web 2012 Demonstration. Published December 9, 2011. Consulted April 2, 2019 https://www.museumsandtheweb.com/mw2012/programs/the_online_collection_of_the_walters_art_mus.html

Klinger, Marina. “Working out the Wiki.” Brooklyn Museum. BKM TECH. Published March 4, 2015. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/community/blogosphere/2015/03/04/working-out-the-wiki/

Knipel, Richard. ” ‘Wiki-fying’ the Collection: Our First Wikimedian-in-Residence Looks Back on 2017.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Collection Insights Blog. Published December 28, 2017. Consulted April 3, 2019. https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/collection-insights/2017/wikimedian-in-residence

Lee, Willy. “Why Not Google: Is There A Future For Content Aggregators Or Distributed Searching?” J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). In Museums and the Web 2004 Proceedings. Published March 2004. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://www.museumsandtheweb.com/mw2004/papers/lee/lee.html

Lih, Andrew. “Combining AI and Human Judgment to Build Knowledge about Art on a Global Scale.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Now at The Met Blog. Published March 4, 2019. Consulted April 3, 2019. https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2019/wikipedia-art-and-ai

Lincoln, Matthew. “The Tate Uses Wikipedia for Artist Biographies, and I’m OK With It.” Matthew Lincoln, PhD Art History and Digital Research. Published September 9, 2018. Consulted April 3, 2019. https://matthewlincoln.net/2018/09/09/the-tate-uses-wikipedia-for-artist-bios.html

Madewell, Stephanie. “Make Your Own Masterpiece with Rijksmuseum.” Etsy Journal. Published February 13, 2014. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://blog.etsy.com/en/rijks-museum-and-etsy/

Merkley, Ryan. “Big Flickr Announcement: All CC-licensed images will be protected.” Creative Commons Blog. Published March 8, 2019. Consulted April 3, 2019. https://creativecommons.org/2019/03/08/flickr-announcement/

Pekel, Joris. “A history of Europe’s relationship with culture.” Europeana Pro Blog. Published September 2, 2013. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://pro.europeana.eu/post/a-history-of-europes-relationship-with-culture

Peters, Diane. “Europeana adopts new data exchange agreement, all metadata to be published under CC0.” Creative Commons Blog. Published September 22, 2011. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://creativecommons.org/2011/09/22/europeana-adopts-new-data-exchange-agreement-all-metadata-to-be-published-under-cc0/

Powerhouse Museum. “Powerhouse Museum Collection 2.0 beta” July 2, 2006. Wayback Machine. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20060702053955/http://www.powerhousemuseum.com/collection/database/https://web.archive.org/web/20060702053955/http://www.powerhousemuseum.com/collection/database/

Rackley, Marilyn. “Internet Archive.” Encyclopedia of Library and Information Sciences. Third Edition. DOI: 10.1081/E-ELIS3-120044284. Taylor and Francis. 2010. https://archive.org/details/internetarchive-encyclis/page/n1

Recode Staff. “Full transcript: Internet Archive founder Brewster Kahle on Recode Decode.” Recode. Last Update March 8, 2017. Consulted April 3, 2019. https://www.recode.net/2017/3/8/14843408/transcript-internet-archive-founder-brewster-kahle-wayback-machine-recode-decode

Roncero, Letica. “Celebrating 11 years of The Commons.” Flickr Blog. Published January 16, 2019. Consulted April 3, 2019. https://blog.flickr.net/en/2019/01/16/celebrating-the-11th-anniversary-of-flickr-commons/

Roth, Matthew. “Walters Museum uploads 19,000 photos to Wikimedia Commons.” Wikimedia Foundation Blog. GLAM, OUTREACH. Published May 8, 2012. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://blog.wikimedia.org/2012/05/08/walters-museum-uploads-19000-photos-to-wikimedia-commons/

Salas, Solimar. “Lori Byrd Phillips, Digital Marketing Coordinator, The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis.” musete.ch. Published October 21, 2013. Consulted April 3, 2019. https://musete.ch/2013/10/21/lori-byrd-phillips-digital-marketing-coordinator-the-childrens-museum-of-indianapolis/

Shaden, Brooke. “Creative Commons.” Flickr Blog. Published June 29, 2004. Consulted April 3, 2019. https://blog.flickr.net/en/2004/06/29/creative-commons/

Sharpe, Emily and Jose Da Silva. “Art’s Most Popular: here are 2018’s most visited shows and museums” The Art Newspaper. Published March 24, 2019. Consulted April 3, 2019. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/analysis/fashion-provides-winning-formula

Simonite, Tom. “Inside The Alexa-Friendly World of Wikidata.” Wired.com. Published February 18, 2019. Consulted April 3, 2019 https://www.wired.com/story/inside-the-alexa-friendly-world-of-wikidata/

Sood, Amit. “Explore museums and great works of art in the Google Art Project.” Google Official Blog. Published February 1, 2011. Consulted April 3, 2019. https://googleblog.blogspot.com/2011/02/explore-museums-and-great-works-of-art.html

Stacey, Paul. “Rijksmuseum Case Study: Interview with Lizzy Jongma.” Made with Creative Commons on Medium. Published September 25, 2017. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://medium.com/made-with-creative-commons/rijksmuseum-2f8660f9c8dd

Stierch, Sarah. “Walters Art Museum: A case study in sharing.” OpenGLAM Blog. Published January 22, 2013. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://openglam.org/2013/01/22/walters-art-museum-a-case-study-in-sharing/

Stierch, Sarah. “Walters Art Museum goes CC0.” OpenGLAM Blog. Published July 30, 2015. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://openglam.org/2015/07/30/walter-art-museum-goes-cc0/

Stimler, Neal. (nealstimler). “Museum collections publishing to Wikidata and Wikimedia Commons through automated processes. Also, museum collections online becoming more like Wikipedia with multiple and real-time editors, including those external to an institution.” Published March 10, 2019 9:17 AM. Tweet. Consulted April 3, 2019. https://twitter.com/nealstimler/status/1104778298364755968

Wallace, Andrea and Douglas MacCarthy. “Survey of GLAM open access policies.” Spring 2018. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1WPS-KJptUJ-o8SXtg00llcxq0IKJu8eO6Ege_GrLaNc/edit#gid=1409426267

Walters Art Museum. Walters Art Museum Application Programming Interface Documentation. GitHub. Last update August 7, 2015. Consulted April 2, 2019. https://github.com/WaltersArtMuseum/walters-api

“Strategy/Wikimedia movement/2017” Wikimedia Meta-Wiki. Last Updated February 7, 2019. Consulted April 3, 2019. https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Strategy/Wikimedia_movement/2017

“History of Wikipedia.” Wikipedia. Late Updated April 3, 2019. Consulted April 3, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Wikipedia

Cite as:

Stimler, Neal, Rawlinson, Louise and Lih, Andrew. "Where Are The Edit and Upload Buttons? Dynamic Futures for Museum Collections Online.." MW19: MW 2019. Published April 4, 2019. Consulted .

https://mw19.mwconf.org/paper/where-are-the-edit-and-upload-buttons-dynamic-futures-for-museum-collections-online/